I was involved in a serendipitous exchange today on Twitter, that started with my friend James musing about yetis possibly being a kind of undiscovered polar bear. I said that given the evidence of polar bear distribution of polar bears and yeti sightings it would be unlikely but not impossible for it to be a kind of bear. One of his followers, Helen, joined in and said something about dinosaur skeletons being reassembled in weird ways to make monsters and it got me thinking about Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and language teaching.

SLA is a relatively new science, much like paleontology. We know some things from observing evidence (if how people appear to learn or not in SLA; of typical anatomical arrangements in paleontology) and making hypotheses to test in order to go on and construct theories.

We also have language teaching. Some language teaching is informed by SLA and some is not. Some fossil gathering is done by people who read up on paleontology and some is done by people who are interested in finding cool stuff, and some is done by accident.

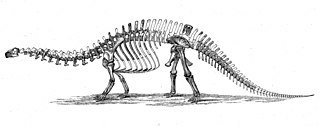

What’s the point? Well, have you ever heard of a brontosaurus? Of course you have. It’s a massive thing with a long neck and a long tail. And the wrong head for years. And endless debates about whether it is the same as an apatosaurus. There is mainly scientific agreement to say the brontosaurus is a kind of apatosaurus. There are still some who say it warrants a distinct genus.

There are plausible ideas in language teaching. Grammar can be learned in a linear way from simple to complex, that massive exposure leads to massive gains. Unfortunately the evidence doesn’t hold up. Grammar (or actually morphology) appears to be learned in a sequence of acquisition with a lot of gaps in the evidence, rather like the allegorical dinosaur skeletons. Some people will go with what we know from science and hold out for the gaps to be filled before making bold claims. Others may try to put a pile of bones together to make a “Harryhausen Cyclops” (thanks Helen) and hoping it’s so, despite a lack of evidence or even overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

There’s also overplaying what science says and making conjectures look like fact. What colour are dinosaurs? Green, yeah? Lizards are green. But not all. There are lots of different coloured reptiles. The skin colour of dinosaurs is conjecture, based on evidence, but taken as fact, per se. Babies are exposed to loads of language, babies get fluent in a language therefore exposure equals acquisition? Perhaps, but there are more factors than that, as any migrant language teacher knows from colleagues who are exposed to the local language but never acquire it (and often never bother to try and learn it).

So what? Well, I think that, no shit Sherlock, getting more SLA literate and informed would help the profession to be less like would monster makers but more like people putting a stegosaurus together. Or having a collection of ammonites, which, while not sexy, are important to natural history.

Tag: evidence

The Personal Side of Evidence-Based Practice

“Evidence based”. It’s so trendy, it’s science-tastic, you the forensic teacher in CSI (Classroom Sciencey Instruction). How many research papers we have found Open Access, through Sci Hub or requests hashtagging #ICanHazPDF!

It’s not all about reading research. Sometimes it’s more about doing very small-scale research to see what happens. Sometimes using recording media, sometimes just paper and pens.

A lot has been written about Action Research by much better brains than me. Anyway, this is a guide to what I might do in a personal action research project.

Gather thoughts

Research for the sake of it is just making work for yourself. What might be better is having a think about what you’d like to understand more about in your classroom(s). Write it down, and keep asking yourself probing questions, for example:

What about this could be a problem?

Is there simply a difference in personal values?

What would do I think is happening? Is this ideal? Is it definitely true?

This is likely to make your findings more compelling to you because they’ll be less superficial and you will understand already what the connections may be to other aspects of your practice.

Design your evidence capture

How you gather your evidence depends upon your classroom and the people in it. You might ask learners to help, or not. You might track your movement, or not. You can use post-it notes to stick in places, on items, etc. You can tally things on paper. You can record yourself on video, audio, or even log your steps taken with a pedometer. What and how you capture it is an important thing and you want accuracy but also ease of use if you don’t have a team (or peer) to help.

Check it before you forget it

You need the time to check your gathered data. Can it be interpreted in more than one way? Which way has most significance for you? It’s likely to suggest further action/intervention or continuing the action you were already doing. If it’s something different, you might need time to prepare and read up on how to do this, or get advice from someone who already does it. Also, keep your information somewhere you can find it. If your new action gets challenged, you want to be able to say why you’re doing it.

More data

As you take your new action/intervention, you may want to write down what happens when you do it, both positive and negative. It may be that any information is not strongly suggestive of anything: rather than stop, give it time or tweak it according to your intuition but write down what you did differently. You might find that the first way was the best way (or not). You might find that this intervention is not as good as what happened before. This is fine, because at least you know that this does not work for me/this class/this situation.

Decide what happens next

This could be a repetition of the same cycle, it could be that you feel you’ve finished it, it could be a return to the status quo. Keep your findings, though. It might be grist for the mill if you or a colleague have a similar train of thought in the future.