Before I started in my current job, I’d taught a presentation course for two years when I was part time at one university, and also as parts of courses at two others. Everyone thinks that they know about presentations because everyone has seen presentations. That is like saying everyone knows how to teach because they have been to school, or everyone knows how to drive because they’ve been in a car or bus.

Teaching Presentation Skills this Spring semester was one of the most successful courses I’ve ever taught. It was a mixture of in-person and in-class, and every in-class session was hybrid because there were some international students that couldn’t get landing permission due to COVID restrictions.

This being Japan-based, a lot of the teaching centred on design, both of posters and of slides. Japan is famed for its amazing graphic design. Sadly, this does not usually translate to amazing slides, in my experience. Also, most posters I have ever seen have necessitated getting up close and squinting. My eyesight is bad enough to need glasses but it’s still not dreadful; the fact is that a lot of posters are journal articles or essays in disguise.

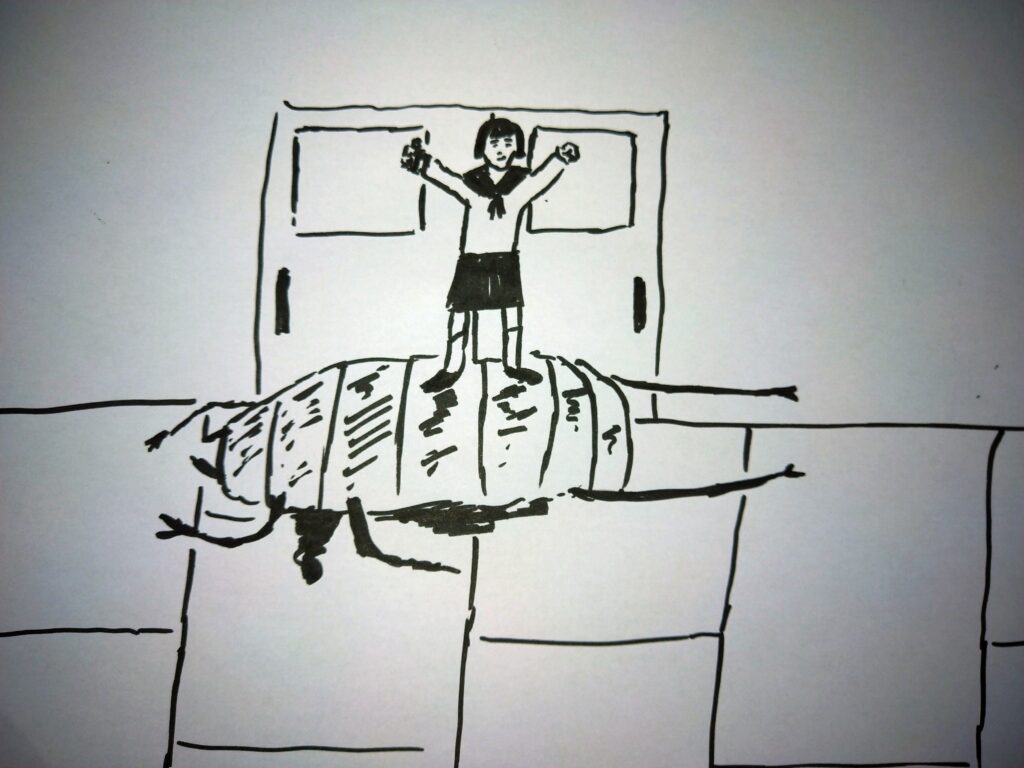

So, the design message could have been ‘be minimal’. However, it wasn’t. Mostly it was, ‘Not everything that comes out of your mouth needs to be on screen/on your poster.’

Also, because these were university students, mainly in their first year, there also needed to be a lot of ‘Please do not read a script because it sounds dreadful. Know your material well enough to talk about it like a human. There is a great quote by EL Doctorow (in Lamott, 1995) about driving with car headlights and that you can’t see everything but you can see enough to find your way.

I also used some of the principles in Nancy Duarte’s books Resonate (2010) and Slide:ology (2008), as well as Garr Reynolds’ (2007) Presentation Zen. Basically, practice, think about why people communicate and what you want to see/hear when you watch a presentation, and how to make a persuasive call to action.

Largely, the design elements went incredibly well and some of the elements of good slide design made it across to work in other courses I taught to some of the same students, which is always good to see. However, with concentration on the what was being said, I noticed that for some students there was not enough ‘oomph’ in how they said it.

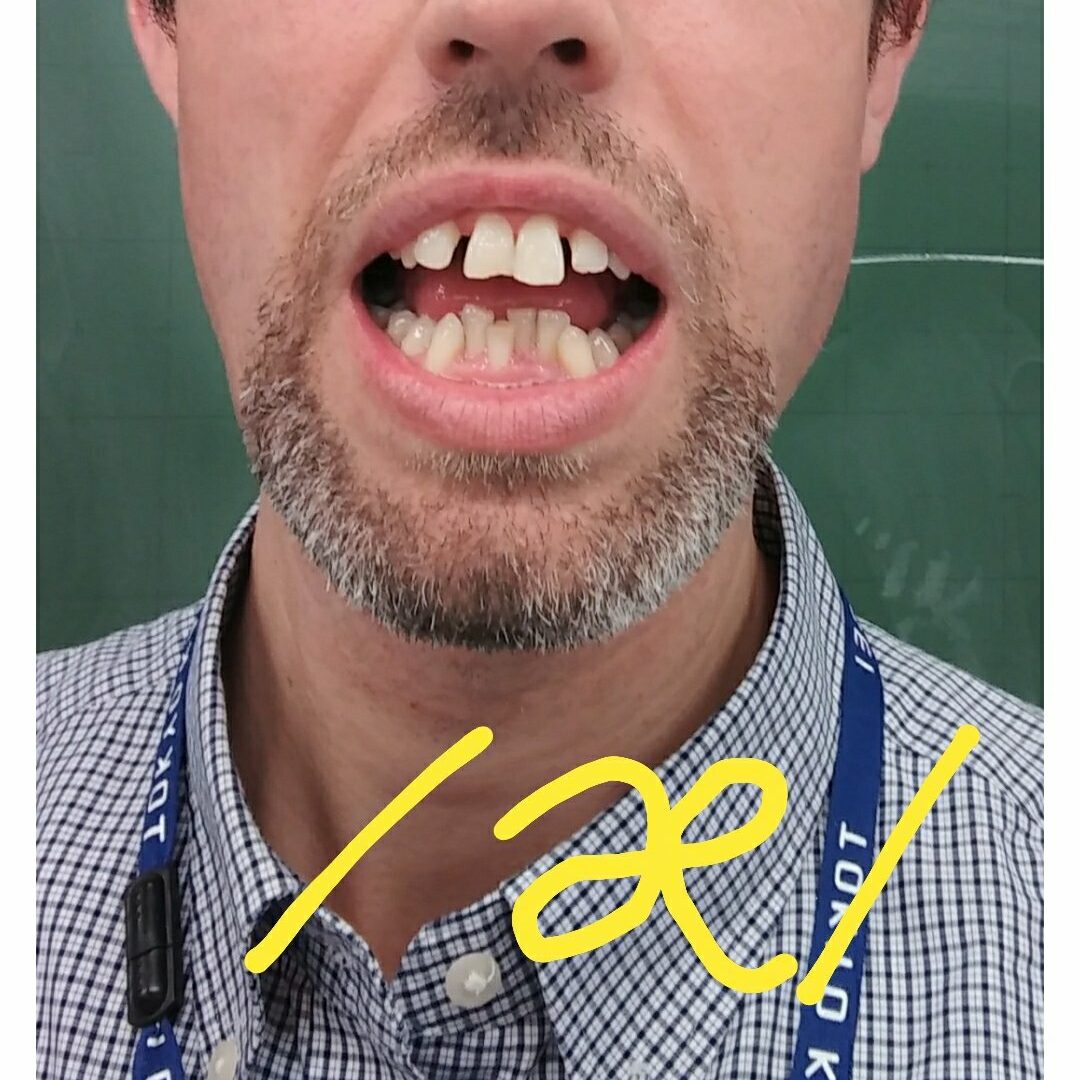

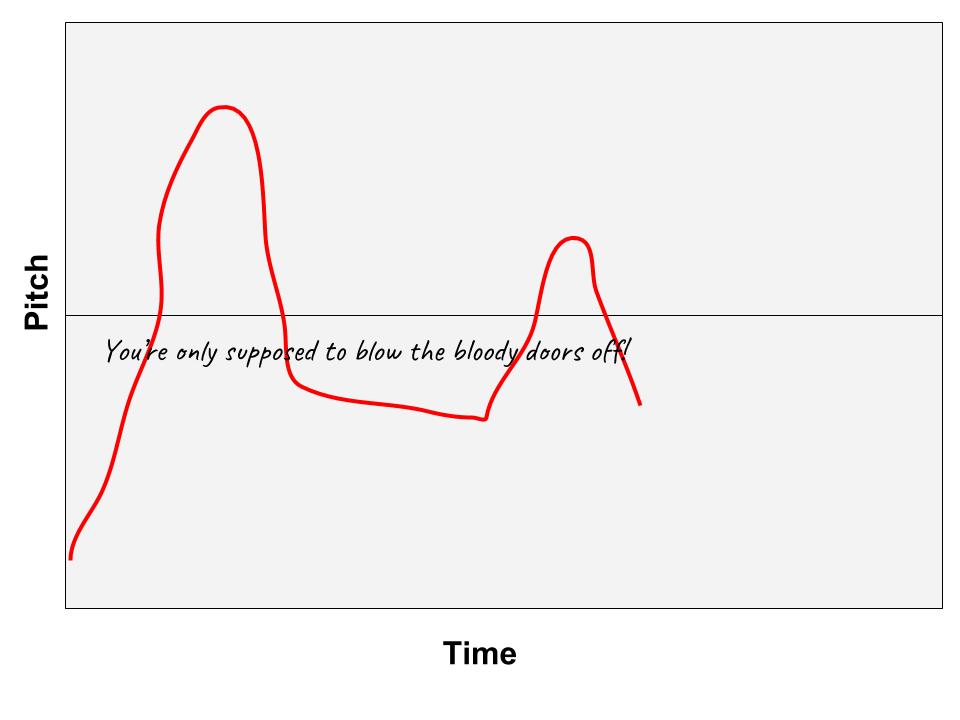

At the time I was reading English after RP by Geoff Lindsey, and it gave me an idea about intonation, especially in our international, Global Englishes (Rose & Galloway, 2018)/ELF (Jenkins, 1998) setting. If the pronunciation is clear, all well and good, but people need to hear the important parts, and follow along. With unpredictable rhythm, that has no reason other than memory blocks, people watching (i.e. other students) will have difficulty and stop paying attention, but by following a ‘normal’ rhythm, using stresses and feet, it is easier to get that polished feel in their presentations. This bit seemed to be most popular with the students, even if I felt a bit daft, clapping a metronomic beat as they mumbled their speeches to find the stresses.

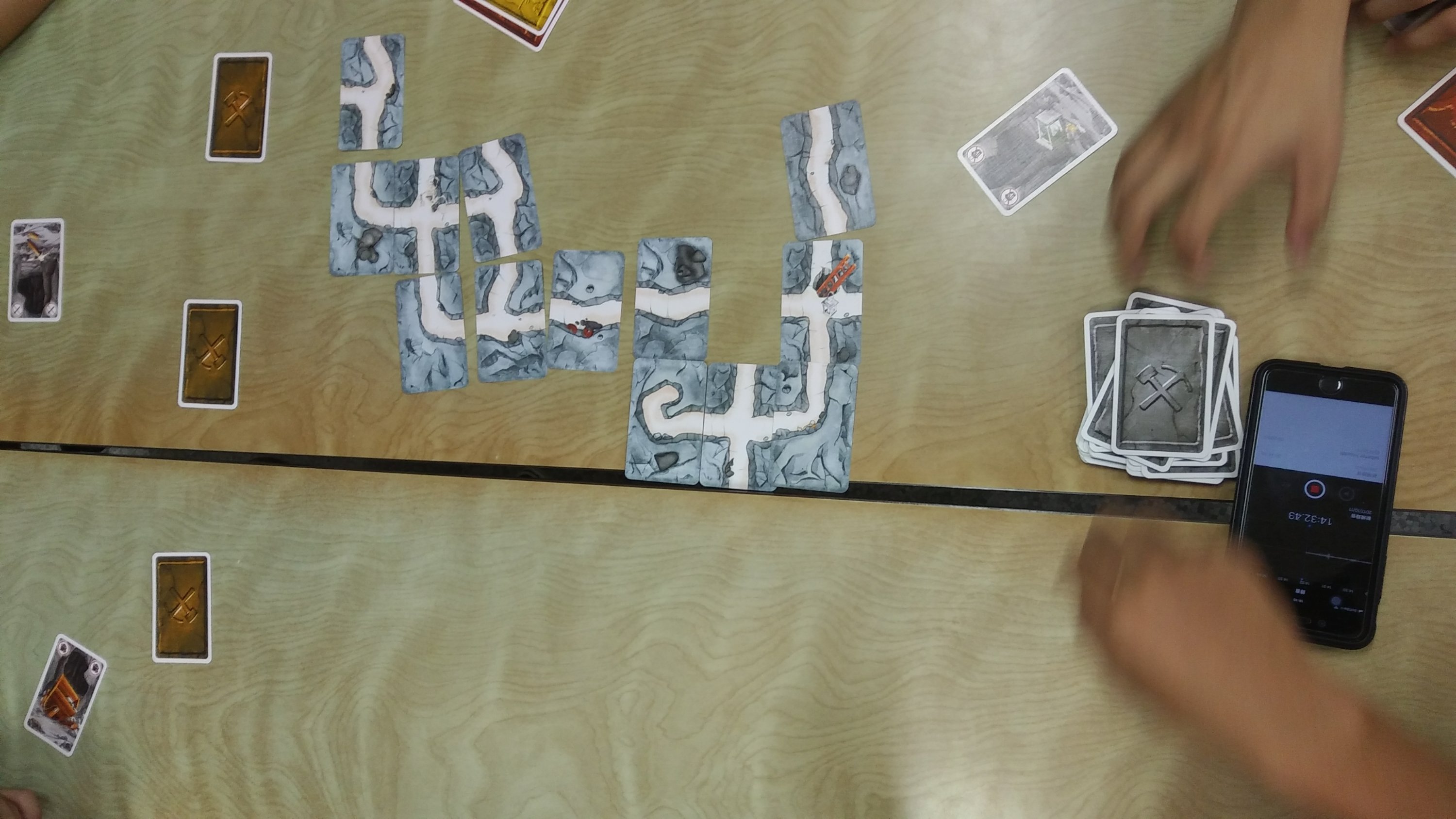

With posters using the Better Posters template (Morrison, 2019) in Google Slides to work with a partner, and group presentations using Google Slides, some students were saying “Why can’t we use Canva?” and I explained that Google Slides is better for version control when collaborating. The final presentation was a solo presentation and could be given with any software they liked. Lots chose Canva, some Powerpoint, some Google Slides. All were at least OK and some were truly amazing.

I’m still going to tweak the course, by probably including an abstract submission as part of assessment, and connection to the abstract in order to reduce students rushing in the early hours instead of brainstorming early on in the process. If I can make it just as enjoyable and rewarding next time around I will be happy. And I know this sounds like a brag, but when you have successes (and creating the opportunities for students to shine is a success) you celebrate them.

References

Duarte, N. (2008) Slide:ology: The art and science of creating great presentations. Wiley

Duarte, N. (2010) Resonate: Present Visual stories that transform audiences. Wiley.

Jenkins, J. (2012). English as a Lingua Franca from the classroom to the classroom. ELT Journal, 66(4), 486–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs040

Lamott, A. (1995) Bird by bird: Advice on writing and life. Anchor.

Lindsey, G. (2019) English After RP: Standard British Pronunciation Today. Palgrave.

Morrison, M. A. (2019, May 8). #betterposter. Retrieved from osf.io/ef53g

Reynolds, G. (2007) Presentation Zen. New Riders.

Rose, H., & Galloway, N. (2019). Global Englishes for language teaching. Cambridge University Press.