I finished my DipTESOL last week, thus I have time to sleep (after I wean myself of 7,234 cups of coffee a day) and, well, blog.

I was in a conversation on Twitter last week with another teacher about bullying in the classroom. How can teachers prevent themselves from being bullied in the classroom by students. I’ve also been thinking about levels of classroom autonomy that I give.

Bullying of teachers by students happens more often than people think. It can happen with children’s classes, teens and adults.

Root Causes

My opinion, and reflections of classes where I’ve been bullied, is that there’s a difference in expectation for the classes. I’ve had a bunch of nine-year-old girls complain to the head of the school/franchise owner because I wasn’t ‘fun’, where fun was endless card games and hangman. I did play these but I also made them speak English in actual conversations, the cardinal sin. It was a relief to finish the contract.

There has been a university class where I had to “lay down the law” because only three of thirty five were on task, using English or even L1. I left the class, telling the students they would not be marked present unless they got on with the work they were supposed to do, but made it clear I would be outside if anyone had questions.

Now I have a better relationship with that class. Boundaries were re-established and the learners are aware of their responsibilities. There are parameters set at the start of the lesson that I will only mark learners present after I hear them speak English x times.

Parameters, Boundaries

I think all learners need boundaries and parameters to work within. I think it is one of the things that has helped me use Task-Based Language Teaching, too.

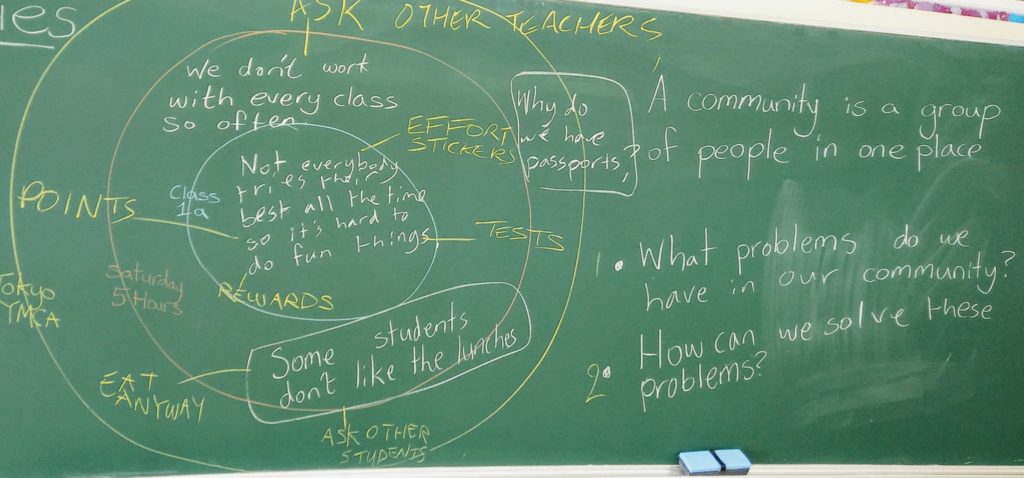

Make clear and negotiate what is OK and not OK at the start of the course (my mistake with the girls). If there is a reason, give it. “Endless hangman means you learn nothing.”

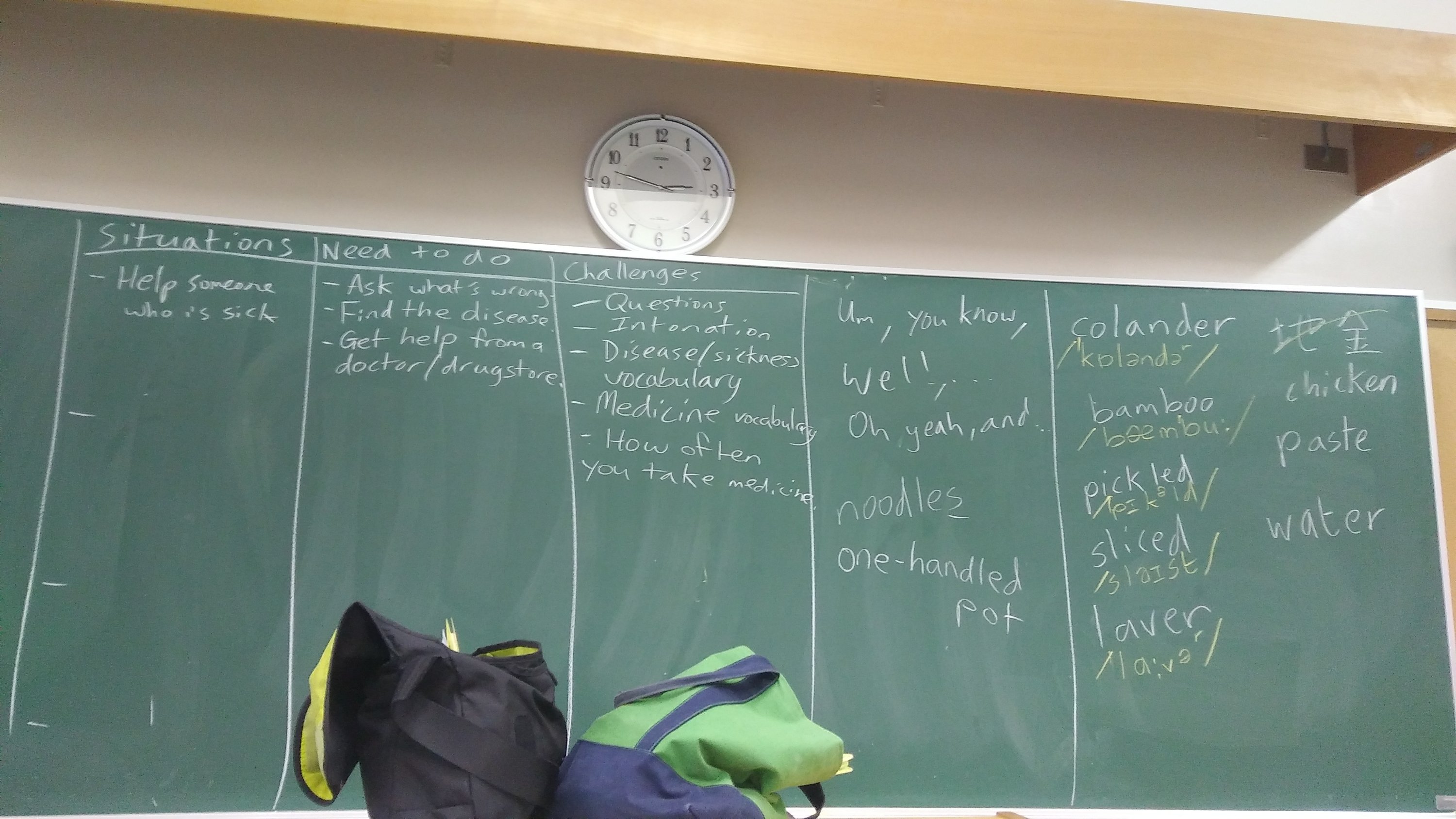

Set parameters and/or success criteria for every task. I do this for almost everything now, about expected language complexity if I know learners will use overly simple language, time limits (asking learners how much time they need), groupings, fluency, etc.

Example:

“Talk to each other about your best friend. I want two details about appearance,” (gesture by running hand from head down) ” two personality details,” (gesture by putting hands on your heart) “and three more interesting details. I think seven minutes is OK but you have ten minutes.”

Board “2 appearance details, 2 personality details, 3 other interesting details, 10 minutes”.

If you can negotiate success criteria with your learners, so much the better.

How About Ambiguity?

Some learners don’t deal with ambiguity and vagueness well, and perhaps won’t ask for clarification and then be paralysed by a fear of doing the wrong thing. The solutions are either rigid parameters and instruction checking (not my favourite, to be honest) or a looser, wider acceptable range of outcomes that foster autonomy of decision making, judgement and let learners follow an aspect of the task that interests them (very much my favourite). That isn’t to say it’s a free for all; you still need to monitor to ensure there’s learning and/or application of learning happening. Don’t be afraid to pause tasks for clarification and stop them when they turn out to be too easy or too difficult, (but have an idea about what to do next).