You are in a classroom. There is a dais with a desk, behind which there is a blackboard. In front of you there are eight novices awaiting instruction.

I choose to engage the novices.

Go ahead.

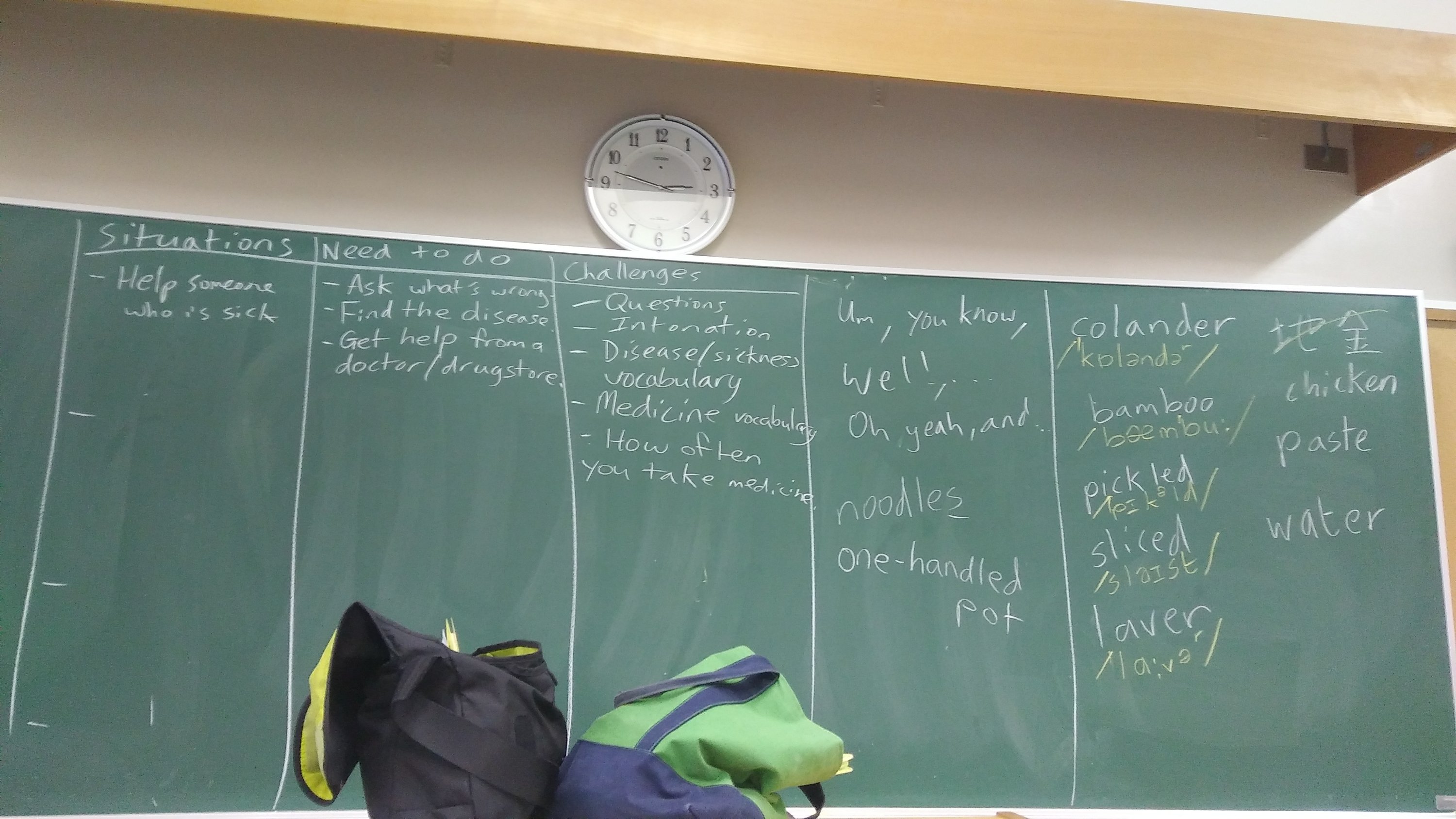

Today, I have a plan. However, I am interested to know if you have a different plan. My plan can be for another day. Please imagine different situations that you and Rob or Vanessa (our regular Non-Player Characters) might be in. Use last week’s lesson as a planning guide. If you need help, please ask me.

Roll D10>3 and D4<4 for successful engagement and +1 courage.

D10=7,

D4 falls off desk… =1.

It went really well, actually. The students planned in two groups of 4. One group decided on explaining a road relay (and did very well indeed), and the other planned to teach how to make miso soup, which they underestimated the complexity of, but I see this as a good learning experience. I also think that by giving my students a metaphorical look behind the curtain that they can understand the success criteria for the tasks I create a bit better. I would still like a bit more linguistic complexity in their output, but today I am going to take this as a success.

XP +D6

D6=4.

Read Here be (Dungeons and) Dragons previous ‘chapters’: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Tag: task

"This is gold!"

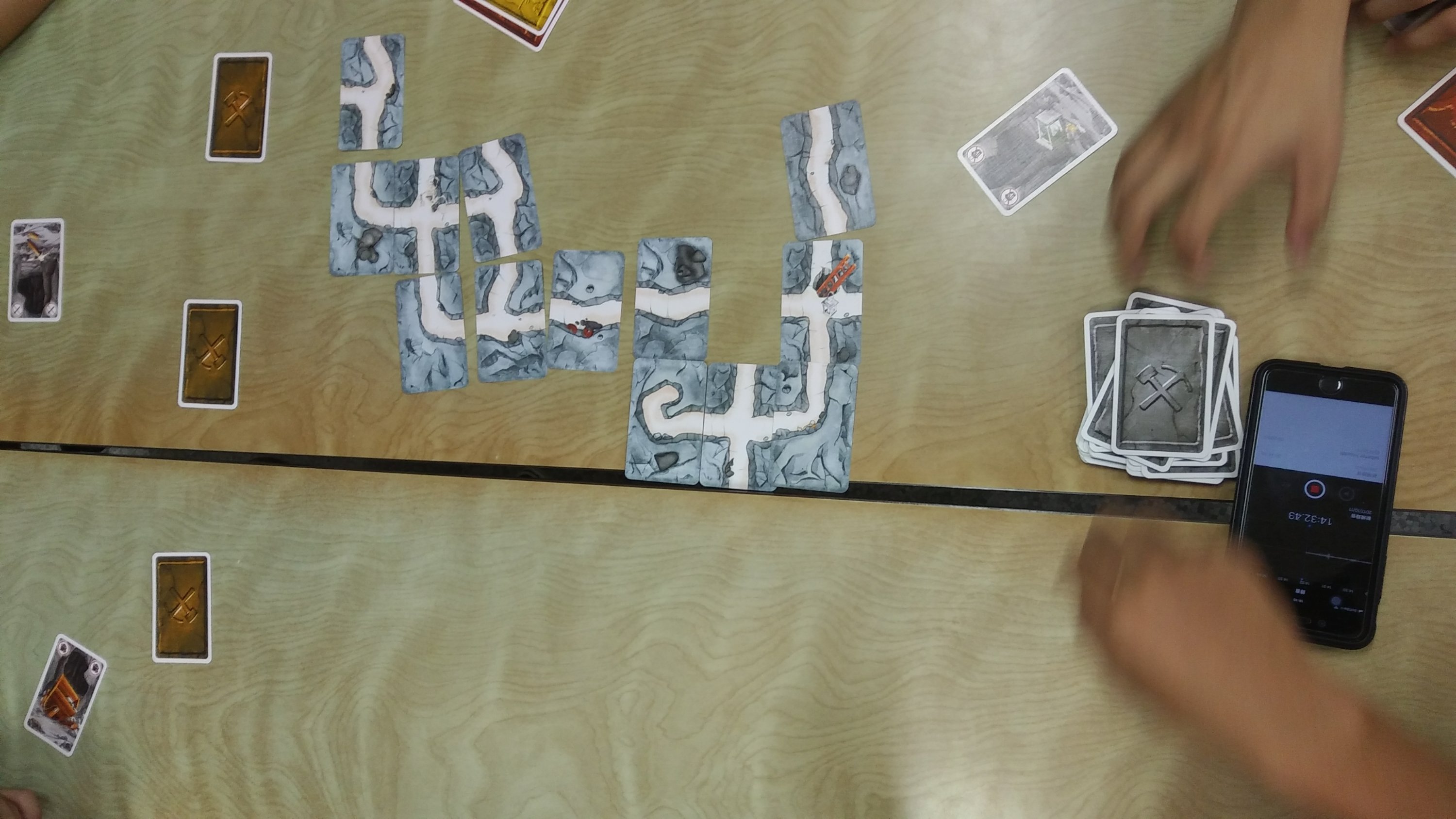

I’ve been using Saboteur with an adapted Kotoba Rollers framework by James York with my university classes. I want talking with authentic tasks, which games provide. There is also transcription of language used. It isn’t all fun and games though.

In the game, players are either good, hardworking miners or saboteurs. None of the players know the roles of the others but they hardworking miners need to work together to get the gold. The saboteurs need to ensure the pack of cards is exhausted before the treasure cards are reached. There are also action cards such as breaking tools, fixing tools, causing rock falls and checking maps for gold, which may lead to cooperation or subterfuge.

The published rules are a bit tricky to understand. I had set the reading for homework, figuring that if there were a lot of difficulties the students would use dictionaries or Google Translate. This means my students skim read them superficially and did not bother to understand the rules fully before game play. Dictionaries and Google barely got looked at.

However, the rules needed a bit of clarification. This led to some good negotiation of meaning (Long, 1983). There are cards used to destroy the mine path above or break other players’ tools but they weren’t always easily understood.

The transcription is the main part I changed. I ask students to write three parts.

What did your partner say? Did they say it differently to how you would say it? How would you say it?

This has been done pretty well and is usually the best part of my RPG-based classes’ sheets, too.

What communication problems did you have? Why?

This sometimes ends up being a wishy-washy “I need to speak more fluently” but a lot of my students have gone a bit deeper.

If you spoke Japanese, what did you say? How can you say it in English?

This has an obvious function but students do sometimes half-arse it and just use Google Translate one way without checking the translation in a (monolingual) dictionary or Skell.

Still the work got done and there was another game of Saboteur in the following lesson to review. I was satisfied with this little Kotoba Rollers cycle, and so were my students, though I needed to buy 4 lots of the game for my big class.

References

Long, M. (1983) Native speaker/non-native speaker conversation and the negotiation of comprehensible input1. Applied Linguistics, 4 (2) pp. 126–141.

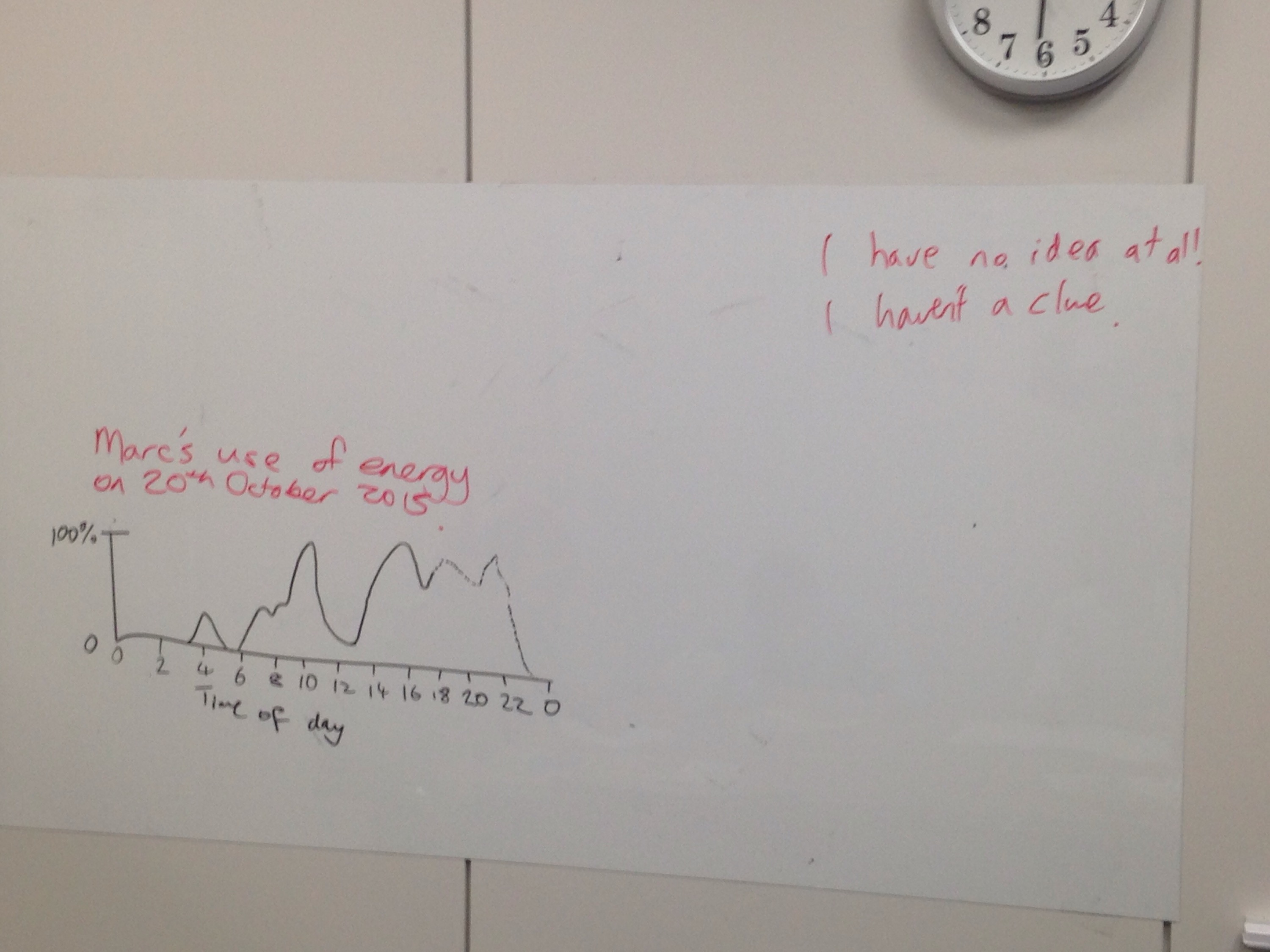

Travel Problems – a Dogme-ish lesson

In this post I’ll go over a bit of a Dogme-ish (and I say Dogme-ish because it’s kind of Task Based due to the syllabus that I knocked up based on the absolute lack of any definite needs for my university students other than ‘learn some English’). With that, I designed a bit of a travel-based task cycle, of which every lesson stands alone or links. This is the final one in the cycle and perhaps my favourite. This is a role-play lesson with a bit of a difference.

- Give out slips of paper. Tell students to each write one different foreign travel problem on the slips. They don’t need to worry about spelling very much because it’s not the point of the lesson. Take all slips in.

- Put students into groups of 4 or 5 (I’d say groups of 3 might be too much work for one person – you’ll be assigning rotating roles to the students). The rotating roles are speakers who role play each travel problem and two or three listeners who listen to all or some of the following:

- Grammatical accuracy;

- Lexical appropriacy;

- Pragmatic competence;

- Pronunciation;

- Communication strategies;

- Fluency;

- What they would do the same or do differently.

- Give the slips out, ensuring groups have as few duplicates as possible. Set the students to plan one role play (not script writing – focus on speech acts and reactivity) as a group for students 1 & 2 in the group to perform for 6 minutes. Then have students 1 & 2 perform the role play while 3 & 4 listen and then give feedback. Teacher monitors and takes notes.

- Focus on Form. Probably a good idea to cover things you noticed but the student listeners didn’t.

- All students planning again – 4 minutes this time. Students 2 & 3 perform, 1 & 4 listen then give feedback.

- Focus on Form.

- As previous planning and roleplaying but with 2 minutes planning. 3 & 4 perform, 1 & 2 listen.

- Focus on Form again.

- No planning. 1 & 4 perform, 2 & 3 listen and give feedback.

- Student groups pick the most successful role play. Teacher randomly (or not) selects pairs from each group to perform, gives feedback.

TBL/CLIL-ish Lesson: Paper Aeroplanes

Who doesn’t love paper aeroplanes? I mean apart from the person who has to tidy them up?

This is an easy lesson to do and could take about an hour to two hours depending on how many plane types you teach.

I took different sets of instructions from www.paperaeroplanes.com and told my students to practice making the plane. I made sure to tell everyone they would be teaching how to make their plane later.

The vocabulary needed was in the reading but be aware that inattentive students may ignore it. I would have them read and copy out a list of ten or so useful vocabulary items if I did this again. Focus on form was given as we went.

There was the opportunity to ask meanings of words as we went along and the instruction task was passed if planes were made and failed if they didn’t.

Plane types were tested for speed, height and distance. Students then wrote up a short report.

As extension work, we tried folds to the wings and fuselage to see if the planes would turn or roll.

The students loved doing this and everyone was speaking English all the time. There was even more negotiation of meaning than usual, too.

Actually Doing Task-Based Teaching

It’s hardly a secret that I love Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT). I think it gets learners using all the language they know, trying to use stuff they kind of know and provides chances for them to realise what they don’t know.

It’s hardly a secret that I love Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT). I think it gets learners using all the language they know, trying to use stuff they kind of know and provides chances for them to realise what they don’t know.

Saying all that, it has a rarefied image and the books that link it to SLA theory sometimes disguise the fact that it is straightforward to do in your ordinary classroom.

Beware

- You are giving learners the space to use language as they wish. They may stick to overly-simplistic forms. You must correct this.

- If you have a grammar syllabus to follow, TBLT may not be the best choice because you should be looking at task completion in an appropriate way both in how and what language is used. If you are looking at past continuous and set a task to tell a story, in Task-Based contexts your success criteria is telling a story appropriately; within a grammar syllabus you need to assess grammar. I’m not saying you can’t teach grammar with TBLT but you don’t expect students to use specific structures 100% correctly by the end of the lesson. You’re looking for appropriate communication and learners noticing things they can and can’t do. Monitor constantly.

Planning

The old chestnut of plan backwards. “What do you want the learners to do by the end of the lesson?” The answer to this should not be a grammar structure, though you might focus on this. “Use appropriate opening gambits to start conversations and continue conversations with appropriate questions” would be better. There are some tasks here.

Set the parameters of the task: how long, how many people, what does the output/input look like, expected level of fluency, accuracy, etc.

Is there anything that the learners definitely need to complete the task? Specialist vocab for topics and situations can be elicited as a pre-task before jumping into it. Planning and anticipating steps of the conversation may be another. If there are structures/patterns/collocations to be taught, do it in the Focus on Form.

Focus on Form?

Yes, this is according to Mike Long (2015) a focus on appropriate language use and its form rather than prescriptive grammatical structures.

I often base this on errors/avoidances, like a long error correction but going deeper into usage and further examples. Drills, ‘games’ and such might go here. Focus on form does not have to be just grammar: pronunciation, morphology, pragmatics (appropriacy), and anything the learners have displayed a need for might go here.

Repetition

You can repeat tasks, report tasks, present tasks and so on at the end. Learners need to reflect on what they did in the task and what has been taught. This part should ideally have greater fluency/accuracy/complexity.

This Sounds Long

Perhaps. How much time have you got? I didn’t say it all had to fit into one lesson. Dave and Jane Willis (2007) have a bit about Task Cycles in their book Doing Task-Based Teaching.

The Normal Flow (for me)

- Pre-Task (Elicitation or some kind of schema activation).

- Pre-Task (Possibly an exemplar task, reading/listening for info).

- Task.

- Corrections/Focus on Form.

- One of the following: Evaluate and report as a group, Repeat task with different partners, Use previous task info as part of a new task, Redraft/remake previous task output.

If there are glaring errors, let me know. No doubt this is not *best practice*. It is a quick guide. Teachers will find their feet. Play with your lesson timings, don’t be afraid to pause tasks, split or change them if your learners find them too hard. I hope you have fun.

References

Long, M (2015) Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

Willis, D & Willis, J (2007) Doing Task Based Teaching. Oxford, OUP.

TBLT ELT – Reading Gallery Task

This is a task from the TBLT ELT LinoIt board (more info on its page) that I did with my pre-intermediate reading class at university. This was a replacement task for a dull spread comparing two cities in an otherwise OK set text.

For homework they were assigned to get information about a city from a brainstormed list and print it out.

About two thirds did the homework. This was enough and I knew that I could rely on the majority of the class to generate enough content.

Aside: I did try to get some students who hadn’t done the homework to work together to try to catch up by finding 5 interesting facts about a major city but this was pointless as the lazy students were lazy and the forgetful but relatively conscientious ones did all the work instead.

I then had the students pin their printouts/notebooks/paper to the wall with adhesive tack (Blu-Tac). I then set the task: read as much as possible and rank the cities by livability.

Pairs read as much as possible within five minutes after being told reading different parts from each other would enable greater coverage. They then did the ranking exercise and reported back to the whole class on their top two and lowest one. This generated vocabulary through different pairs’ questions and also grammar awareness through written recasts on the board.

After the main bit I had the students take down three vocabulary items (chunks or words). I boarded them, corrected pronunciation and elicited student definition where possible.

The students said it was a bit difficult but that it was interesting to read up on several very different places.

I’m pretty sure I’ll do something similar again if only because it generated so much language that came from the students