Here in Japan it is nearly the end of the academic year. A whole academic year of the fallout from COVID-19. Anyway, clearly anything to do with that is horrid, so I want to write about something good. Maybe even useful.

I have been teaching Authentic Listening at one of the universities I work at for 3 years now, although this is the first year that I have taught it at the advanced level. We had a lot of students that couldn’t go on their study abroad programmes this year and they needed courses at the appropriate level. I planned the syllabus out kind of last minute because I wasn’t 100% sure I would end up teaching it. Anyway, it has been largely successful, with one or two caveats which are the same caveats that come up in all remote teaching this year (i.e. students aren’t used to learning online, synchronously, and universities are not willing to reduce the course load on teachers sufficiently to make asynchronous teaching practical). The best thing, in my opinion, has been my shift to focus students more upon reflective practice (which I also did in my Rapid Reading classes this year).

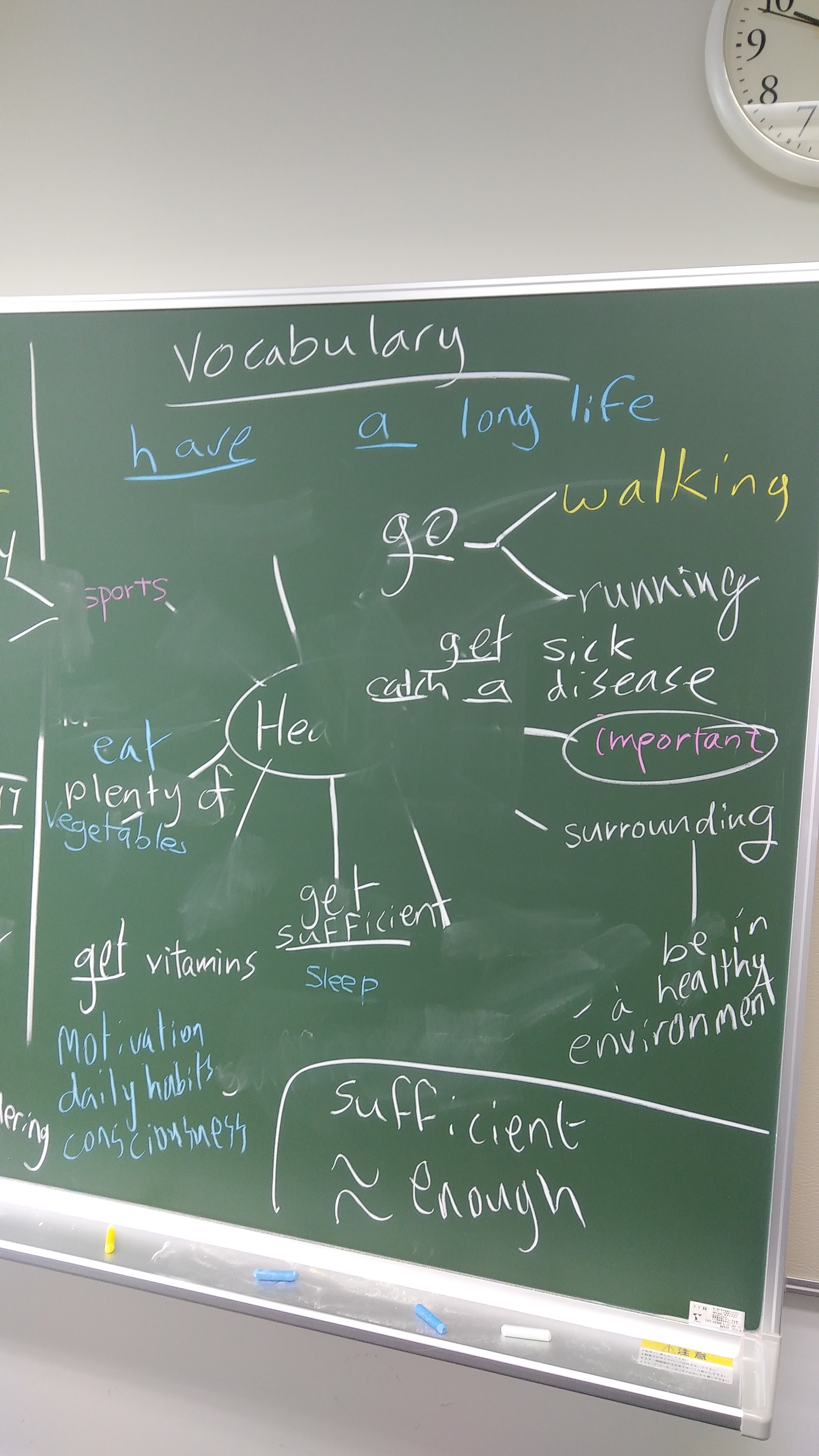

What did the students reflect on?

I got my students to reflect upon their difficulties and successes in listening. Reflecting on the difficulties also entailed thinking about possible solutions to lessen the difficulties, but in an autonomous way. This is because I can’t always be there to help. A lot of the difficulty is possibly because students have not really considered how they might be able to help themselves, nor have they even been given sufficient time to reflect on their difficulties.

Some students found this so difficult to do in a meaningful way at first (mainly due to the reluctance to interact with students they don’t know, I think), but later there were some very good ideas indeed. In final presentations (worth 10% of grades) there were excellent ideas about future autonomous listening study, and the students who were quiet and not interacting with others very much showed me that actually they were invested in the class and not just faffing while their cameras and mics were off. I am quite an insecure person and I know that most people don’t care nearly as much about listening skills development as I do, but this class showed me that actually, interaction is not a proxy for skills development or a proxy for attention to information/applying the information.

Outcomes

Basically, a lot of students realised that their phonological knowledge improved if they paid attention to it and used the IPA to take notes of things, though this is difficult. They also became more amenable to not attempting to write down every single thing that was spoken in the things they listened to. Some students even went further and tried to find out about aspects of connected speech, segmentation and juncture, and intonation related to problems they had with their listening. The best part was not that these are solved problems, but that my students realize that they are only partially solved but they have the tools to work on the solutions outside of the (virtual) classroom.

Conclusion

Reflection can be a good thing but it needs to be structured if it is going to be useful at all, otherwise you get fake reflection, or reflection without further action. Here, part of a difficult skill is made the responsibility of the learners rather than the teacher(s) so classroom time can be devoted to things that actually need more intensive teacher involvement, or teacher advice.