The other day I had a lesson with my TOEIC class at one of the universities I teach at and we were having a vocabulary review. I decided to check knowledge of collocations by using some collocation forks and have my students check things out using COCA.

That part of the lesson worked well; after getting the students used to productive use of the corpus and reducing the number of lines, all was good. Checking things like ‘take in’ they found that it has mainly visual or cognitive stimuli that collocates.

It might have looked like my students were having a faff about on their phones but if I don’t teach them how to use a corpus in lessons, they probably won’t be able to use it without guidance at home.

I have in the past used Twitter as a corpus with students but it doesn’t work very well to give concordances all the time.

If you are interested in working with COCA, you should definitely give Mura Nava‘s Cup of COCA posts out.

I Love It When A Plan Comes Together

As a teacher, I have a love/hate relationship with lesson planning. I love to have already planned, but I hate writing the plans. I’m pretty decent at thinking about tasks to do and the language use and activities to stimulate such use but when it comes to hammering it into MS Word, I don’t feel that I do myself justice. Whack it on a scruffy bit of notepaper and it’s brilliant.

Anyway, there was a Twitter discussion between Anthony Ash, Marek Kiczkowiak and I about the benefits of a detailed plan for observed lessons and such based on Anthony’s original post. Basically, the consensus was that detailed plans can be useful for professional development but that it doesn’t always occur. Marek and I said that the 10-page lesson plan is a waste of time seeing as it’s probably going to be binned, but that a bunch of Post-Its or bullet list would be fine provided one knows the reasons why one is doing what one is doing and how one is going to do it.

Anyway, it got me thinking about Preflection, a post on Steve Brown’s blog from ages ago, how knowing your learners is essential, and how taking notes in the class is important. It got me thinking about needs analysis as well.

It is my belief that all good reflective teachers carry out a needs analysis of their learners on the fly, either error analysis or just finding out about their motivation for learning. We then reflect upon these needs and make judgments about how to alter our practice to facilitate the student’s uptake of language regarding these needs. It got me thinking about incredibly detailed diagrams by Long (1977) and Chaudron (1977) in Allwright and Bailey (1991: p.101, p.106) showing the multitude of decisions that language teachers make in the classroom just for error treatment.

Because of this, I don’t think that having a hugely detailed lesson plan is important because whatever you do in the classroom occurs in the classroom at that particular moment; given this fact, the context changes due to affective factors such as learner moods/states-of-mind and effective factors such as new work assignments requiring different language skills to those previously needed or an impulsion to talk about something highly topical. The aforementioned bulleted list is, in my opinion, sufficient and a healthy allocation of contingency time useful in order to indulge learner whims.

References

Other than internet sources linked to above,

Allwright, D and Bailey, K. (1991) Focus on the Language Classroom. Cambridge: CUP.

Status Update/MEES Michinohe.

OK, so in the last week, this blog has massively increased it’s readership (great thanks to all who shared the post on Coursebooks).

I gave my presentation at MEES Michinoku at Hachinohe Gakuin University and found it wasn’t as contentious as I thought it might have been. I have no scars from things being thrown at me. I also got the chance to meet a lot of cool people and I saw some interesting presentations with practical application to my classroom practice. Of particular note was John Campbell-Larsen’s plenary about discourse/conversation analysis and corpus findings about common speech and conversation. There was two particularly fascinating sections on backchannelling and evaluating in conversations that have helped my students in the last few days.

The slides from my presentation are here if you want to have a look at them, and there may be even a YouTube later so you can see just how nervous I felt!

In the meantime, I’ve had loads of back and forth on Twitter/blog comments with Rose Bard and Glenys Hanson, both of whom I wholeheartedly recommend!

Coursebooks: the Thick and the Thin End of the Wedge

I have used some rubbish books in my time as a teacher. I have not used many great ones but I have used some half decent ones, the caveat being that those books were targeted at specific business skills or selected skills that learners needed (based on a pre-course needs analysis).

Anyhow, I have found myself dragged into coursebook debates a few times on Twitter and I am going to refrain from entering any more of them for one year after this post unless they end up being useful for my Master’s degree studies.

There are some excellent critiques of coursebooks: Geoffrey Jordan (1, 1.5, 2) and Rosemere Bard give well-reasoned takedowns (1, 2). The only defences I’ve seen for textbooks that seem to hold any weight are from Twitter people Anne Hendler and Tim Hampson, that teachers are worked too hard to plan several different lessons and select materials so having something to take in to class is a godsend, although the defences were nuanced and acknowledged that the materials were not perfect. The defences I’ve seen from materials writers are less rigid.

Mike S. Boyle posted a defence that focussed on the general sales pitch of coursebooks.

I’m going to look at these six points now.

1. You are a busy, overworked teacher and you don’t have time to prepare.

Possibly this could pass muster. However, the amount of time taken to mine a textbook text for useful language could be done with the newspaper or another authentic text on the way to work or within a few minutes. And by text I mean audio or video as an option there, too. You could also put the onus on students to bring in something they’d like to look at or set them homework to find out about a topic that interests them and report their findings (and/or further questions) to you. It’s going to generate some discussion at least, and if it is coming from the learners it is going to generate language about a topic or situation they want to talk about.

2. You are new to teaching, your school has given you little or no training, and you need obvious structure and guidance.

You had no training? Not even a ‘Teach Yourself TEFL’ book from the library before you boarded a flight? Well, perhaps the coursebook will appeal to you for the first couple of weeks until you bore yourself senseless with the same topics raising their head over and over again. And you’ll be repeating those lessons until your students get to the next level, which will lead you to supplementary materials and realia so you don’t have to look at the book again. If you are lucky enough to have a good book at a crap school that doesn’t care about its teachers then excellent, use it. However, if your school cares little about your training, they’re unlikely to care about your materials, are they?

3. Your class is huge and your students are either required to be there or do not seem to have clear goals for studying English.

If your class is huge, a book is of no consequence. The resources you have are the resources you have. Are you really guiding a class of fifty, sixty or seventy in lockstep through the present perfect? Or do you have several groups of four or thirty-odd pairs having a meaningful conversation about a topic that is likely to interest them and then talking to others in the class?

4. Your students are traumatized from junior high and high school English and are terrified of speaking and making mistakes.

This is unrelated to the book. You can help shy students prepare with offline planning of tasks by writing down what they want to say, asking partners for help and then have them negotiate meaning in a conversation. Yes, Language Classroom Anxiety is a real phenomenon, but having a grammar syllabus on the table is going to help nobody shake the anxiety, no matter how friendly and zappy the illustrations may be.

5. Your students have had a lot of prior exposure to English (though it may not have stuck) so you know you may need to jump in and out of the book a lot, skip over some things, and supplement other areas with extra stuff which you will need to find in a resource pack because you have no time.

If you need to skip over some things, students will start to wonder why they have had to pay between US$20 to $50 for a book that they haven’t covered everything from. Do you skip novel chapters? No, you do not, and a coursebook is a different thing but students want value for money and if they have bought a book they will want to cover it completely, whether it benefits their language development or not. This appears to be setting up some teachers for a fall.

6. At some point in the nearish future, your students are going to have to pass a life-altering high-stakes exam that covers a very specific set of skills, question types, language items, etc.

Yes, they may. Are they being tested on grammar? Then a grammar book is useful. Vocabulary? A vocabulary book. Everything? Then you need to focus on developing their use of language, which a structural syllabus fails to address due to it not taking into account what is learnable by the learners according to their interlanguage state. If they have the chance to learn language through communication and negotiated meaning, allowing them to test internal hypotheses, they are going to internalise the language much more easily than attempting to learn rote the example grammar in the language focus.

Hugh Dellar does acknowledge that a basis of structural grammar is of limited use and that cultural imperialism through the back door is an issue but he does not make a solid argument for the presence of the book in the classroom. I’ve read some well-argued stuff from Hugh regarding the Lexical Approach (which seems like it is an approach desperate to be tacked on to a methodology but this is not the time for that) but his argument doesn’t say anything this time apart from that he is trying something new (yes, he is).

So, now on to my own views.

Books are foisted onto teachers and learners. Generally. Not always, but generally. They are then assumed to be the syllabus for the class.

They strongly favour a PPP approach, and the presentation of grammar in a sequence, often with the presence of review units, frequently a collection of multiple-choice questions.

The listening and reading ‘tasks’ are often multiple-choice insults to intelligence at worst or shooting fish in a barrel at best. If there is an open question it is OK, but this helps to give lie to the status of the teacher or coursebook author dictating the questions that ought to be asked about a text. There are also tons and tons of display questions, which are rarely used in life other than as passive-aggressive rhetoric.

The listening is too often too stupid in that it is ludicrously slow, and completely unlike authentic listening.

There’s little discourse awareness given to learners, with fillers being thrown in occasionally but normally nothing about adjacency pairs or conversation management, the absence of the latter helping to nullify Boyle’s arguments for the book as a crutch for inexperienced or untrained teachers.

Lexically, in many of the structural syllabus coursebooks, there are sets and they are frequently unchallenging due to them being so familiar in students’ lexical landscapes an/or loanwords, so what is the point unless you are looking to separate the front and back cover to justify the price.

Phonemic awareness is given short shrift and even then, learners are given no guidance about what they need to do with their mouths to achieve these sounds (again, what does the fabled inexperienced teacher do here other than talk rubbish about it or hope for the best with magic and accident?). There are no sagittal diagrams or even explanations that diphthongs glide from one position to another so the mouth needs to move when you make this sound.

I think I have covered most of my gripes but if I have missed anything, do let me know by the 7th. Good night.

Teaching or Testing Listening?

Dear Me probably in even 2010,

You get a CD in the back of your shiny book. The shiny book that has a picture of a loudspeaker to show you the track number. You ask the preset questions underneath and you play the CD and there are the lovely voices of the polite English-speaking people, all waiting to speak enthusiastically, one at a time with a handy grammar point in their throats. They are all lovely people who speak in a standard (prestige) variety with as much of their regional accent scrubbed away as possible.

Then you wonder why your students ‘cannot listen’.

Did you teach them how to listen, or did you only check their (lack of) comprehension again?

Nobody taught me how to teach listening. I doubt that the in-house trainers that trained me ever received anything other than a quick mention to ‘make sure you do some listening‘ when they were trained as teachers.

Students learn to listen by metaphorically being thrown in at the deep end. Unfortunately, like swimming, it only works the first time for a few people. Nobody learns to decode at phoneme or syllable level. Sometimes there might be word-level listening but it’s magic and accident. ‘Listen for the word “useless”. What is it used to describe?’

If we want to give students listening practice, all well and good, but don’t call it teaching. Call it listening to the CD, which could be done at home. Teach some connected speech and have students listen for examples of it. Teach some intonation patterns and have students listen for speaker attitude and intention or even how many items they are listing.

You could even ditch the stupid CD, find something online that has real conversations about something the students are interested in (such as a podcast about video games or a YouTube video about a country they want to go to) and play that instead, having them listen for words stressed in the tone units and make sense of it that way.

But don’t press play and tell the students that you’re teaching listening.

Sincerely,

You

Lots of the key ideas here are not mine. Probably most of them come from:

Field, J (2012) Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: CUP.

Prince, Peter (2013) ‘Listening, remembering, writing: Exploring the dictogloss task’. Language Teaching Research: 17(4) 486–500. London: Sage. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

Other #youngerteacherself posts at Joanna Malefaki’s blog.

Adjacency Pairs Sheet

Here’s a nice warm up or quick review for TOEIC-style classes or those where there has been a lack of awareness of appropriate response.

The first sheet is examples to answer, the second sheet is for students to make their own together.

It’s here as a Powerpoint so you can edit it, or a PDF for printing on the go.

Reflection

You can’t teach without reflecting. Apparently.

You sit in a staff room an listening to people moaning about “them” being idiots/dummies/dehumanized amorphous masses; about “them” not being capable of independent thought; about “them” not giving a monkey’s.

You chirp, “It’s because the students are not used to dealing with communicative classrooms and they don’t want to make mistakes. Why not try group work and reporting group opinions if they’re shy or unresponsive.”

You mean ‘I wouldn’t talk to you either if you carried that attitude about me. I’m putting in my two-pence worth because it’s frustrating listening to you.’

“Well, I’ll give it a try but…”

At the same institution you have had students enjoy TOEIC lessons by drawing the focus away from the book and on the thought processes behind the questions set. Students work together to produce their own TOEIC-style materials. You’ve had students give group carousel poster sessions about language study and motivation. You’ve had students survey their classmates and then reflect on whether their survey design was flawed or not. Only one of these was your own idea. Mostly everyone has been on task. Either you have remarkable classes or your students are just in a better mood for studying.

You are exploring your practice. You share ideas. You can advise what works for you and something that might be good to try. In a class full of “them”.

You can’t expect everyone to be enthusiastic all the time. You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.

Various: Status Update

The action research I started is in full swing and the independent study that students were asked to undertake was done by around 80% students in both the sample classes, although some students changed their independent study methods from video to songs and nobody read at all.

I did the listening with my false beginner class today and they really enjoyed it although they found it difficult.

I participated in my second ever #KELTchat on Twitter and it was very informative, especially for my university classes.

Other than that, Twitter was on fire this morning due to my previous moaning arguing moaning about how rubbish bland coursebooks don’t meet student needs but teachers are forced into using them anyway.

I have bad news in that a language school I just started working for is being bought. The new owner seems nice but I do feel uneasy in my work. Conversely, I had an interview with another agency that teaches a lot of IELTS courses. I await that with bated breath, as I do my MA TESOL and Applied Linguistics application.

Authentic Listening Material

I’ve been looking out for some authentic listening material for some of the Business English courses I teach. I just found a website called Freesound which has some fantastic Creative Commons-licensed MP3 and wav files, free to download.

I downloaded some basic train and airport announcements and I am planning to have false beginner students listen for answers to the following questions:

- When does the announcement change to English?

- Which gate can you board the plane from?

In another class I’ll have some pre-intermediate students listen for answers to these questions:

- What is the new platform for the Penzance train?

- Does the Penzance train stop at Exeter St. David’s?

TBLT for Kids. Easy science lesson plan.

This is basically to go with an idea that I am trying to run with. Based on the BerlinLanguage Worker GAS group, I would like to see something similar happen in the Greater Tokyo area. There is the ETJ Workshop series, but that is sponsored by Oxford University Press and what I am really interested in is people getting together to share their ideas and producing lesson plans and/or materials together, with the materials being Creative Commons licensed so that anyone who wants to use them can do so and change them or improve them as appropriate for their setting. If you are interested, get in touch via the comments.

Level:

Pre-intermediate upward.

Lesson Aims:

- Students write a report using sequencing language.

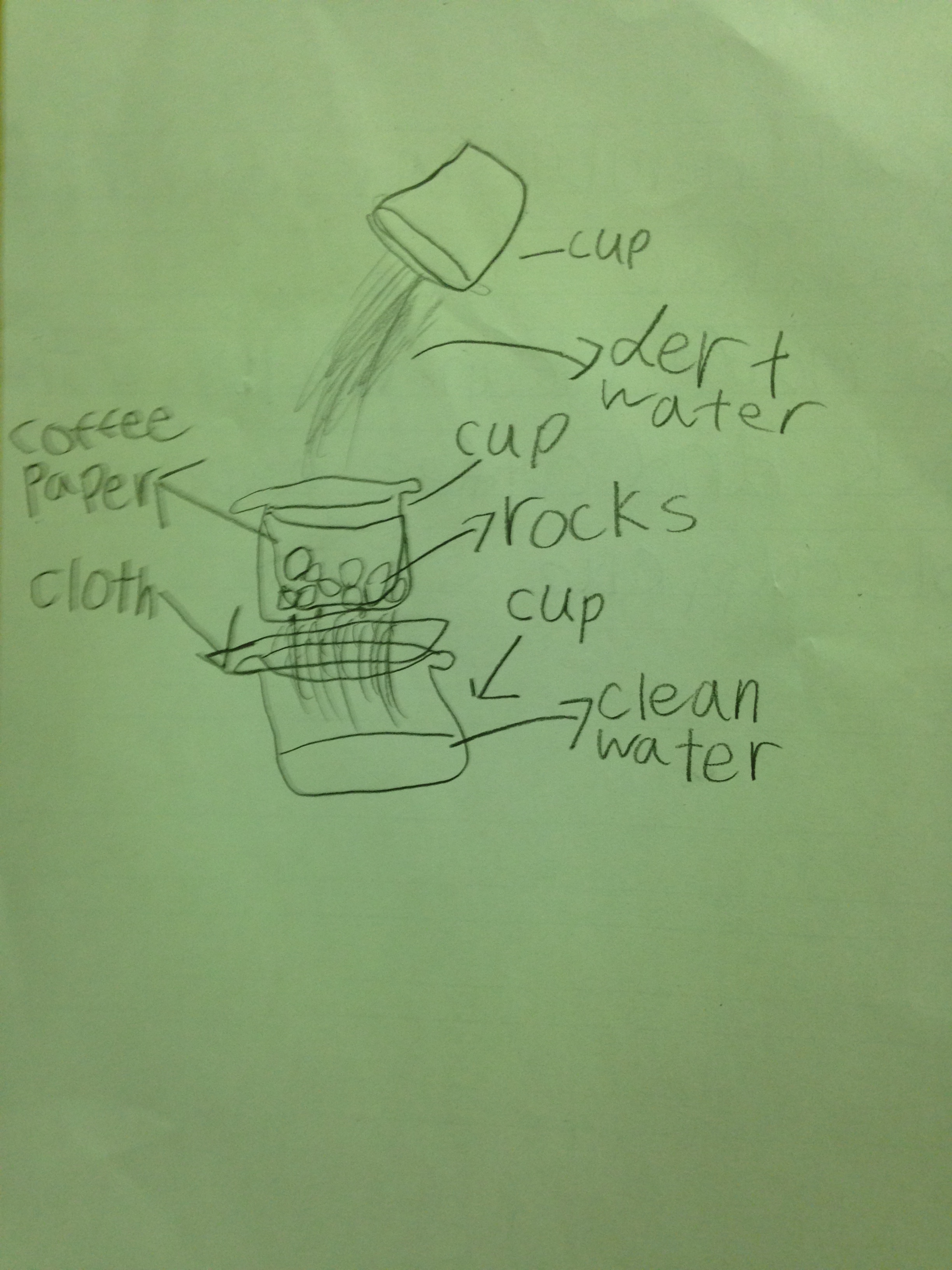

- Students produce a labelled diagram.

Time:

About an hour.

Materials:

Dirt, pebbles/gravel, water, disposable plastic cups (three per group), cloth, coffee filters, a pair of compasses/corkscrew/pocketknife, paper lined one side and unlined on the other.

1. Each group needs three cups. Put holes in the bottom of one.

2. Elicit names for all of the materials.

3. Pour water into one cup for each group and add dirt.

4. Tell students to clean the water. Remind them to use English as much as possible when talking to each other because they may need to write it down later.

5. Students try to clean water. If they don’t manage it after about half an hour drop massive hints or else model it.

6. Students draw a diagram of their most successful filtration setup and label it. You might need to model it, you might not.

7. After diagrams are drawn, students write up what they did. Again, modelling the writing is advantageous and possibly essential depending on the level of the kids.

EXTENSION: Students evaluate their group. Who did what? Who had the most successful ideas.

MAKING IT MORE DIFFICULT: Put cooking oil or sugar in the water.