The heat got turned up this week and we looked at keywords, looked deeper at collocation and colligation and then semantic preference and discourse prosody.

As somebody always about in the internet and reading blogs about teaching, I have kind of got sick of the definition of collocate as ‘the company words keep’. It doesn’t really mean very much, and it could even apply to colligate, too.

Collocate: words that statistically occur together.

Colligate: words that have a statistical affinity for grammatical classes.

Then we get onto semantic preference. This is really interesting. These are basically collocate groups. For example, in a search of the BNC for ‘encounter’ as a noun there are a collocations with: this, first, last, final, after, second, before, every. I would say (and I could be wrong) that this forms a semantic group of chronological markers.

What this means for teachers is that if you plan to teach ‘encounter’ as a noun, you should probably consider teaching it in contexts with these markers, probably as part of a story. This could be part of a prior reflection on words likely to arise as part of a task in a syllabus or, if you’re teaching using literature, that you might want to bring in some other materials if these collocates don’t appear (although there are also collocates with ‘casual’, ‘sexual’ and ‘thrilling’ for all you risque teachers).

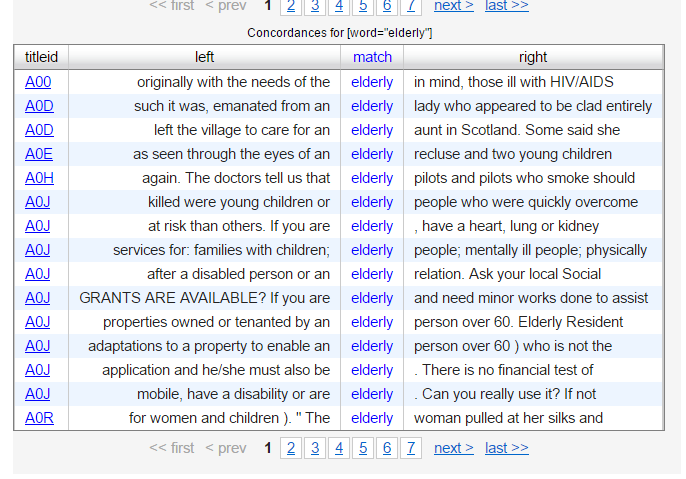

Getting on to discourse prosody, which is the meanings and discourse usually associated with words, this basically has sociolinguistic implications in that how a word is used within a corpus (especially one taken at a specific time/place) tells you about the cultural values associated with that word. Again, in the BNC, if one searches for ‘elderly’ that it appears they need care, particularly health care and that they are vulnerable, which is also backed up by collocations.

For teachers, this means you might look at this word (for recycling especially) when teaching lessons based on health, or talk about health and infirmity when talking about age (and whether these should be taken as a given, of course; always question discourse!)

I haven’t had much time to play with AntConc this week because I want to make a better corpus to mess about with. Still, interesting stuff.

Author: Marc Jones

Author: Marc Jones

Real Alternatives Need Alacrity

It’s that old Corporate ELT is killing me slowly trope. Hang on to your hats, comrades, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

So, the coursebooks palaver came up again on Geoff Jordan’s blog. I have written on this before. The main change in my ideas is that instead of Dogme or Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) being the utopia we should all aim for, what is needed to get teachers to go with something better than a textbook is an alternative.

In the aforementioned post, Steve Brown said that what is needed is not any other kind of alternative but for teachers to take agency: choose what the materials are, or choose to choose with the learners, or whatnot. He is right, but I think there needs to be a bit of handholding to get there.

I’ve seen comments saying that it takes bloody ages to plan a TBLT lesson, and it does when you first start. Similarly CELTA-type lessons take bloody ages when you first start. No qualifications? Think to your first week on the job. Lesson plans took forever. Anything takes ages when you first start.You need to think about whether the initial time investment will pay off or not. You are reading a blog about teacher development, so ostensibly you are open to this seeing as you are reading this instead of playing video games or trolling Trump supporters.

So, let the handholding begin. Or the push to start.

What can I use instead of a coursebook?

Have a think (always a good idea) about what your learners need. Asking them is often a good idea, though teenagers might tell you they need about 3 hours in bed and that they need to do gap-fills of A1 vocab. They don’t. Assess. What can they do? What can’t they do? What aren’t you sure they can do? The answers to this should rarely be “They can’t do the past tense with regular verbs” or something. Maybe “They can’t answer questions about the weekend” is better. Cool. That is something we can chuck into the syllabus, if we think that our learners need this. If they don’t, don’t put it in. But why did you bother assessing it otherwise?

With all this information, you can create a syllabus/course. Sequencing it is a bit of a bugger because you want to think about complexity, what is likely needed toward the start and middle to get to the end, recycling language and such. However, you and your learners have control. This is not the kind of thing to put on a granite tablet. If it seems to need a bit of something else, do that.

But what do I do?

Teach the skills you need to teach. Potentially this is all four skills of reading, listening, writing and speaking. There are books about ways to teach these. You might want to browse Wayzgoose press. Also The Round minis range has some very interesting stuff, as does 52. If you get a copy of Teaching Unplugged, I find it useful.

You and your learners can then source texts from the internet (which a lot of textbooks do anyway so you are cutting out the middleman), edit for length (nice authentic language) or elaborate and spend longer with (that is, put in a gloss at the side or add clauses explaining the language). You can create your own, too, which sounds time consuming but might not be the pain in the arse you think it is. You can also put in some stuff that is rarely covered in textbooks like pronunciation and how to build listening skills, microlistening, and more (a bugbear of mine).

There are also lots of lesson plans on blogs (including here). If you have some good lessons that have worked for you, they might work for others, who can then adapt them. With a book, there are sunk costs and learners will want to plough through the lot if they have bought it. If you have a lesson plan to manipulate, without having sunken money into it bar some printer paper, you and your learners get more control and hopefully smething more suited to them than something chosen by an anonymous somebody in London or New York.

If I’m going to use texts, I might as well use a textbook!

You could, but think of all the pages of nonsense you have to skip. Think of the time spent with learners focussing on pointless vocabulary like ‘sextant’ (thanks Total English pre-intermediate). You have an idea. You know your learners, or at least the context. There is also a ton of stuff on the internet. May I point you to the Google Drive folder at the top of this blog. All the stuff in there is Creative Commons Licensed so you can change it if it isn’t perfect, copy it for your learners, and because I already made it and was going to anyway, it’s free. There is also Paul Walsh’s brill Decentralised Teaching and Learning. There are also ideas to use from Flashmob ELT.

So

You have these ideas to use, modify, whatever and put into timeslots. You can move them around. You have the means, now, if you decide it’s worth a go, stick with it for a few weeks at least, so you can get into the swing of it. If you like it, leave a comment. If you hate it and I’ve ruined your life (and be warned that not all supervisors, managers and even learners are open to this at first. Check, or at least be aware of this. If your learners say they want a book they might just mean they want materials provided and a plan from week to week) leave a comment.

If you think I’m talking nonsense, I’d seriously love you to leave a comment. Tell me why.

If you want help with this, I’m thinking of using Slack for a free (yes, really, at least initially) course type thing, say an experimental three weeks, where I help you sort out how to go about things (together; top-down isn’t how I do things), help with any teething troubles and so on. If you’re interested, contact me.

Well, Sunday night, eleven o’clock and 1000 words. I’m going to bed. Let’s sleep on it.

#CorpusMOOC Week 1 notes

I joined the Futurelearn/Lancaster University Corpus MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) this week to supplement the module on technology and corpus linguistics I’m studying for my MA.

So far, so good. I’ve managed to watch all of the video lectures and I’ve done a good deal of the reading. It’s just a bit of a dip of your toe in the water this week but it was useful to read about different types of corpora as well as how to read the frequency data and so on (spoiler: think of source material and how wide it is).

One thing that did come up that I wanted to reflect upon was something said in one of the lectures:

Corpora may be used by language teachers to check frequency of occurrence so they may decide to teach their learners more high-frequency items.

It sounds right but then what about sequences of acquisition? Sure, single words, especially simple nouns or verbs might be chosen, but could it be the case that some high-frequency structures are acquired later than less frequent ones? I think I have more reading to do!

Foolish Utopianism in Teacher Development?

Prologue

Prologue

I was going to go to a conference relatively recently but at the last minute I decided not to because I hadn’t actually looked at the price. I thought that because it wasn’t the JALT (Inter?)national conference (nor was it a JALT event at all) that it might be relatively cheap, also seeing as it was at a university campus.

I nearly vomited in my mouth at the price when I saw it. Seeing it there, I hope the keynote presenters were paid for their time, especially seeing as it was unlikely that major publishers would have been paying for them.

1. Possibilities vs. Practicalities

I know that space with nice chairs and decent coffee doesn’t come for free but I also know that some of the teachers who give a damn about their CPD or lack of it can’t afford to pay the equivalent of US$200 to see someone give a talk or workshop that may (or may not) be useful for them in their context.

I’ve never really been that interested in any of the ‘name’ ELT people bar Scott Thornbury and Luke Meddings because what seems to be the case at IATEFL is that facile reinforcement of (perhaps erroneous) beliefs is what draws the attention on the internet, with the exception of Silvana Richardson’s NNEST plenary and Russ Mayne’s Myths in ELT presentation. Geoff Jordan complains about the IATEFL palaver, with big names. To justify a large cost I suppose they need names, but why not cut the costs?

I’ve never been able to get to big conferences due to work but the ones I have made it to have been highly participatory and kind of grassroots. I have also loved many of the webinars I’ve attended and some stuff that might fly might be a hybrid of the two.

2. The Interzone of Cyberspace and Meatspace

Imagine 20-odd people gathered in a space with a mike, a projector, a webcam and several others watching online, feeding questions for the speaker into a public Google document or Twitter hashtag. Imagine 20-odd others in another space in another country watching on a projector, while one of them has the familiar stomach-cramps related to their upcoming presentation-come-workshop.

Google already allows live streaming on YouTube and there are other providers, too. Electronic Village Online has already done web conferences. What about face-to-face with an electronic function? The live-tweeting phenomenon points in this direction, as people seem to want it.

You get to have the communal experience, with networking breaks, yet also have people presenting that you’d never see because they would never normally be able to make it due to time/money/family.

3. Outreach

What good is a conference when it is an echo chamber? Why preach to the choir? In Japan, we need chain eikaiwa teachers and dispatch agency ALTs to come and listen but, more importantly, make their voices heard. Do you know why there is little action research or exploratory practice done in eikaiwa? It isn’t the companies, because people could be taking notes on their regular students, and often do in the roll books. It’s because the teachers know that nobody outside is reaching out to them. Nobody gives a monkey’s. Yet these people do ditch the book, do try out-there things with their students from time to time. I know it would help more of them (as it helped me) to learn more about SLA without it seeming high handed. It would help them if they saw principles put into practice in a workshop. If they could hear people like themselves elsewhere, and also unlike them, with new ideas and alternative perspectives, it would help massively. If it were made accessible, through technology, at cultural centres or coworking spaces, this could easily happen.

4. What could this be like?

It could be like Lesson Jamming.

It could be like Edcamps.

It could be like Electronic Village Online, the ToBELTA web conference, iTDI’s summer webinar season.

It could be like JALT Saitama’s Nakasendo, or Michinohe MEES linked to different locations, available on mobile phones and laptops and projectors and TVs.

If you are interested, message me on Twitter.

Book Review: 50 Activities for the First Day of School

Walton Burns (2016) 50 Activities for the First Day of School. Alphabet Press. US $1.95 ebook. $6.95 pbk.

You know me. I am cynical. I am down on every kind of thing. I do not review products – I rail against the status quo. I only do Dogme and task-based teaching because of their cool, outside-the-mainstream-ness. I don’t do book reviews.

Didn’t.

I had never been asked before, and while I more or less knew that Walton Burns’ book would not be my kind of thing. His Alphabet Press indie publishing venture is an admirable thing; some say that self-publishing is vanity publishing but I think this is a myth put out by big publishers to avoid doing anything worthwhile but keep selling dreck. Anyway, he asked nicely, I said are you sure you want me to tear you apart and then stich you back together with gravel where your soul once was and he said he was sure this wouldn’t happen. I am trying to be less of a negative person, so I said yes.

Still, the book is not my thing really though there are some things I really like.

Things I liked

It is obviously rooted in practice. You can imagine that these activities have been tried and tried again. The variations of the activities are good, and usually more difficult than the original. Some activities are quite contrived but they get students talking. Though I say contrived, it’s no bigger a contrivance than the average EFL classroom. There is also a lot of moving around which can be good for young-ish learners. There is a very good activity about having learners talk about their strengths in the language. The time capsule activity is good as an activity to later compare to the baseline to see progress. There were rough time limits, too, and I’d think about making these subheadings (of which more later).

Things that weren’t for me

I knew the book wasn’t my thing. It’s very icebreaker heavy and I’m not an icebreaker kind of guy. I normally ask learners to find out about each other but not “five things”. Life isn’t constantly numbered.

I think the memory chain activities were rather over represented, too. Memory chains for names in particular. There could have been more for vocabulary (there are some, however).

The English names thing has always made me feel a bit uneasy as it’s often an excuse for monolingual teachers to get out of trying to actually pronounce real names. “Yasuhiro? OK: Joey.” Sometimes I think this is a (this specific) teacher annoyance more than a student one but I honestly don’t know. I’ve taught on courses where students were obliged to pick an English name and there were some amazingly bizarre ones, possibly picked as a piss-take.

The learning myths bit was a bit less student-centred than most other activities.

Would I buy it?

No. But I have been teaching since before my hair was grey. I have seen almost all of these activities before in one iteration or another in various in-house resource books in language schools or just from observing other teachers.

Would I recommend it to anyone?

Yes, maybe. If someone is new to teaching, fresh off a certificate or just on-the-job ‘training’ it might be useful and saves them reinventing the wheel, especially if they have a real academic year (unlike most EFL language schools who take all comers all year). I’d say the ebook would be useful for planning on public transport. There are worksheets available to download for some of the activities which might be nice for those with little experience.

So, I hope this was a fair review. If you write materials and have a desire to have your dreams torn to shreds you can always get in touch.

Your Secret Weapon

For loads of us in a (largely) monolingual EFL setting, there is an amazing resource available under our noses. I’d argue that a lot of people feel it’s a bit rude but I’m going to argue that rude or not, you get to maximize engagement in lessons through greater relevance and also at least partial schema activation.

Eavesdropping on your learners when they’re using L1.

If you can do it, this pays dividends. You get to give them what they are already thinking about but may not be able to do in English. For example, are people on your business class complaining on the phone? Can you help them do it in English, with appropriate language and pragmatic competence? How about the young learners talking about cartoons? Can they explain the plot, the characters or the appeal by involving you in a real conversation?

“What about the syllabus?” you might say.

Can you postpone that item? Work it in? Abandon it? I think we need to remember that syllabi are guides not commandments. And if we make things a bit closer to learners real lives they might want to work through that syllabus a bit more.

Every Little Thing The Reflex Does

I’m showing my age, I know.

I was just thinking earlier, about decision making in the classroom. There’s a brilliant diagram by Chaudron in one of my favourite books, Allwright & Bailey (1991?) Focus on the Language Classroom. CUP. It shows the multitude of decisions we have to make in our classrooms on the fly about error treatment. Add to these the decisions about whether to divert from the lesson plan and how to do it and then it’s an even larger number.

With all these decisions, how do we go about them in a principled way? I feel we do an awful lot based on reflexivity as opposed to reflection. I know that we build up our intuition as we log more classroom practice and think about what goes on but can any of us say every single one of our decisions is planned in advance?

So, the point: I wonder if we logged every reflexive decision and its outcome whether it would help to make better decisions more likely, sort of by step-by-step proceduralizing the metacognitive process (or thinking about what was a good decision and what was a bad decision and hoping that the remnants of this reflection will be accessible the next time you have a similar decision to make).

We can wing it every lesson but is it always the most effective to wing every stage of the lesson all the time? If you’ve done similar things, you can hopefully make similar successes more probable. It’s just making those seemingly more trivial decisions more principled because they might just have ramifications that we don’t anticipate. And as Duran Duran say, “Every little thing the reflex does leaves an answer with a question mark”. Flex-flex!

Diversions

Who hasn’t had a lesson where they’ve followed the lesson plan to get to a very worthy but not especially engaging activity? Students not being interested in different tasks might be related to something unrelated to the classroom, or it could be that in our plans we get a bit over-zealous.

Some experiences I’ve had lately with corporate classes:

Everybody needs to describe their company’s products; nobody likes to do it.

At a company where I teach sales and sales support staff we had a lesson about describing products. The company’s products are highly technical. Everyone did the pretask and exit task well but it seemed to be done with gritted teeth.

What could I have done? Any number of things. The lesson wasn’t bad, but I think it left my students wondering about how bloody difficult the next lesson would be. I could have cut the description into stages: basic spec, example uses, benefits. I could then have united these in the exit task. Or I could have used mass-market products first and then used the client company’s products.

Sometimes what will motivate your students is a discussion about television.

At a software company I was trying to draw blood from a stone by asking about alternative marketing and publicity stunts that could be employed to market their software. This turned into an exercise in going through the motions and then gold in the feedback – just talking about what some interesting TV shows one might watch on a popular internet video platform. This caused my student to switch on, really expand more and give me a gateway to get her to be brilliant next lesson.

So, next time, perhaps I should wing it more, don’t you think?

Taking Control of your Development

This post is basically an extended comment on Clare Fielder’s interesting post, Taking Control of your Teaching Career with the European Profiling Grid.

There is a lot to like about it in that it is systematic – sort of like the CEFR. It also tends to assume that you are intending to spend time near classrooms if not remaining in teaching; DoS-type progression is in it but so is the path of expert practitioner.

There are some flaws in it: it doesn’t really apply exactly to small department contexts. It also stops fairly abruptly; not blowing my own trumpet (well, maybe a bit) but if you’re at the far end already, where do you go next? I don’t intend to leave the classroom to be a Big ELT manager or materials designer for a big publisher, so then what?

These are fairly minor criticisms though, seeing as a lot of TEFLers have a shelf life of about 3-5 years. It would still be an interesting read for anybody who has a few years under their belt but if you’ve worked across contexts, what else is there to do without changing countries or companies for the sake of change?

Synchronized Flashcard Dancing

I’m pretty sure I can’t be the only person who teaches primary-aged children who gets annoyed with expectations about English lessons. The expectations of parents, in turn passed on to the children themselves and then perpetuated by other teachers. Fun is not the opposite of learning but it can be. It can be a right bloody pain to take over a class where kids are used to faffing about in L1 with about half a minute dedicated to language use.

Anyway, here are some of my most hated aspects of some YL lessons. (I may have been guilty of some of these in the past.)

Next to no reading or writing

Reading a bit on one flashcard is not really reading because there’s hardly any other reading in the class, not even shared reading (teacher reading a book with the children). There is often a simple homework exercise matching a word to a picture. It’s not even too easy, it’s so easy as to be pointless. And it doesn’t reinforce learning because it’s either done straight after the lesson before the kids forget, the parents do it the night before or morning of the lesson or it’s forgotten about. But reading and writing aren’t the priority…

Speaking and listening to what?

There are really good kids classes where children acquire basic communicative English skills. I have a feeling this tends to happen when the official syllabus is paid lip service to and the teacher talks to the children about their lives.

Unfortunately there are lessons where ‘Getting around town’ is ‘done’ for 4 weeks, involving a lot of slapping each other’s hands, half-arsed flashcard games and halfhearted singing of songs about things not understood because of a lack of attention, attendance and progression through the syllabus at all costs.

This is not the fault of teachers: it’s the fault of Industrial ELT, with pacing to allow makeup lessons and easy substitutions and replacement with a warm body and a pulse with no training.

Have fun, or else!

Kids lessons must involve movement, games, dancing, singing and touching things. I’m inclined to believe that this is less to do with multi-modality and more to do with hiding the absolute lack of substance in the lessons. I’m all for teaching a little bit of English and doing it well. What games of throw the paper in the bin and shout the name of an animal have to do with anything is beyond me. And synchronized flashcard dancing, mimicking the teacher’s ‘I like carrots!’ might get children to notice the ‘I like’ construction, but quite possibly only for taking the piss out of the teacher behind their back.

OK. Any solutions, Johnny Angrythumbs?

Yes. Do a bit of writing. Write on mini whiteboards, bits of paper, card, whatever. You can make your own flashcard games. The children can copy down the sentences that might have been pre-printed gap fills.

Ask basic questions. Ask absolutely simplified questions. But ask real ones at least sometimes. “What did you do last week?” is nice. The children then see that there’s a communicative need: someone is actually interested in an answer they have been asked for.

Play games but why bother if it’s too tenuous. Make a game together, or read, or talk, or listen to something. But unless your learners like the Hokey Cokey or are interested in vegetables out of context, I don’t see the point of putting “the onion in, out, in, out and shake it all about”. Role play cooking or find out everyone’s favourite foods. But don’t squander the opportunity for about an hour of actual learning happening just because Snap and Old McDonald had a Hospital are set for that week.