Differentiation is, in the educational sense of the word, treating learners differently. Here is what the Twitter #eltchat (transcript) said about it.

What is differentiation?

“What is differentiation?” appears to be such a difficult question to answer that it only got directly answered by one short answer by Angelos Bollas, despite being asked by both James Taylor and Shaun Wilden. Angelos said it is:

“designing and/or assigning diff tasks for diff ss for the same lesson”

whereas Yitzha Sarwono said it is:

“giving students different works for the same subject discussed”

How people differentiate

Talken English remarked that there are always fast finishers that need extra work. Patrick Andrews stated that differentiation isn’t just mixed abilities but also “motivation, backgrounds, etc.” Sue Lyon-Jones also added that sometimes it is appropriate to “have a spread of abilities in one group”.

Patrick mentioned:

“levels are not the same as abilities. – if someone has only just begun, they may be able but beginner”

And Sue Lyon-Jones added that such “‘spiky’ profiles” are common in ESOL.

Talken English said that at their school there is a large gap in ability.

Sue Lyon-Jones said that differentiated homework (such as pre-teaching vocabulary) is useful, and Yitzha said that she set difficult tasks to more able students and similar easier work to students with similar problems.

MariaConca said that differentiation was necessary to cater to different learning styles. Glenys Hanson then mentioned that learning styles have been found to lack any evidence backing them up. Rachel Appleby mentioned that using learning activity styles can be good to ensure learners get different activities that they might not usually choose to do. I said that this would be a good method to counter previous teachers’ labelling of students as things like ‘a visual learner’.

I mentioned that I often differentiate by outcome, to which Patrick recommended and old book by Anderson & Lynch called ‘Listening’. I was asked how I would differentiate by outcome and my example was:

“High: order food with pragmatic appropriacy. Mid: order food (formal lang). Low: order food – no L1”

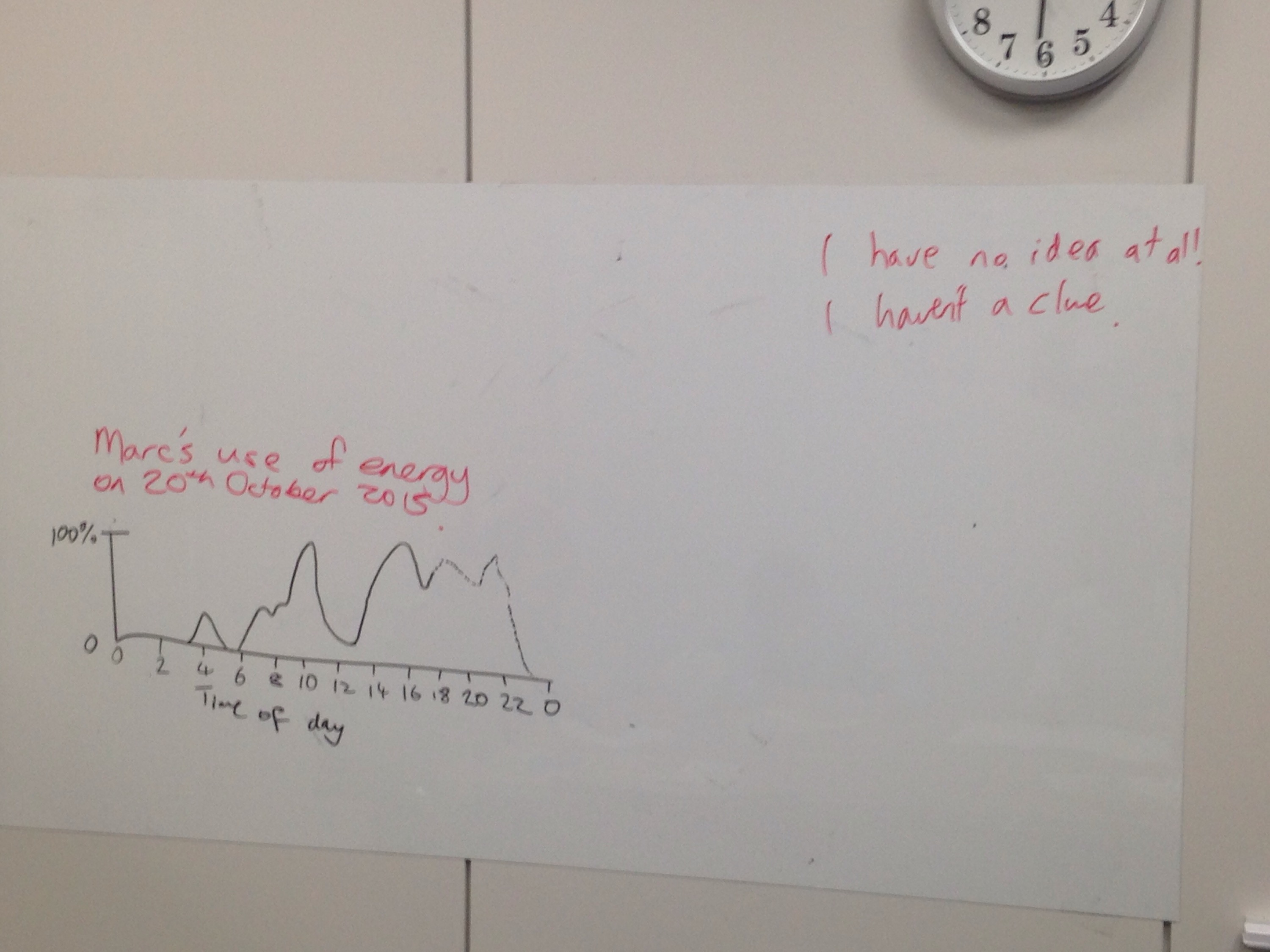

I also mentioned that it can be worthwhile differentiating by mental states, too, and not just ability.

Patrick said he was thinking about using drama in his classroom and that students who didn’t want to perform could take other roles such as directing, etc.

I said that different roles could be set in discussions: overpowering students could be given quieter roles and weaker students could be set as leader to prove their ability.

Sue Annan asked rhetorically:

“can you differentiate the amount of work, rather than the work itself- choose 4 q’s to answer(?)”

Problems with differentiation

Problems with differentiation that were talked about were:

“exposing weaker students. You don’t want them to feel uncomfortable.” (Talken English)

Glenys said

“Ts often project feelings onto students they don’t have. Respect weaker students & they’ll be OK.”

I also said some learners might think they are of higher ability than they really are if they are kept with others of similar but lower ability.

It’s hardly a secret that I love Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT). I think it gets learners using all the language they know, trying to use stuff they kind of know and provides chances for them to realise what they don’t know.

It’s hardly a secret that I love Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT). I think it gets learners using all the language they know, trying to use stuff they kind of know and provides chances for them to realise what they don’t know.