First day back at A University Outside Tokyo today. All new courses as I decided to rewrite the one course that was the same.

Anyway, I have a course for repeating students. I requested this for the challenge and thought it would give me a chance to try new things to up motivation.

15-week role-playing game based roughly on a Dungeons & Dragons-type game mechanic? Based on welcoming an exchange student? Let’s enter the dungeon.

It’s very much a Role Playing course, with a minor game put in. It’s sort of a hybrid of Daniel Brown’s EFL RPGs and James York’s Kotoba Rollers framework. The students have (electronic) portfolios to submit, which should include audio recordings of role plays, transcriptions of part of that audio, vocabulary and grammar notes.

It’s just the first week but the students seem relatively enthusiastic, especially with the 20-sided, 10-sided and 4-sided dice.

The non-player characters (exchange students, parents, etc.) are not played by a Dungeon Master (teacher) but by the students and decided by values of dice rolls. There is a bit of task planning, task recording and task reflection, as well as focus on form reactively.

I still need to work in more about the strength, courage, observation and stamina points more clearly in my mind but at least it wasn’t rejected point blank.

Read Here be (Dungeons and) Dragons future’chapters’: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Category: Pedagogy

Needs Analysis for People Who Don't Know Their Needs

“What do you need to do?” the teacher asks.

“Um, speak English,” the most outgoing student says.

“In what kinds of situations do you use English?”

“Business situations.”

So, not the most illuminating of exchanges to help plan a curriculum. There have been loads of times that this has happened to me, and to others. There’s a lovely post by Laura at Grown Up English about negotiating a task-based syllabus. You might also want a look at #TBLTChat 7 on syllabus design. Here, I’m going a bit hybrid.

With this group of learners I’m going to talk about, I asked their goals and what they usually use English for at work. I got that they want to work on fluency in speaking and listening, on the phone and face to face. There were no concrete situations, though.

Due to this, I get to use my imagination and have a bit of a daydream about other people’s work. Maybe this is due to too much Quantum Leap (“Oh, boy!”) as a boy. Not having the luxury of shadowing the students to find out about a typical day, I can only rely on what they tell me or what I can anticipate.

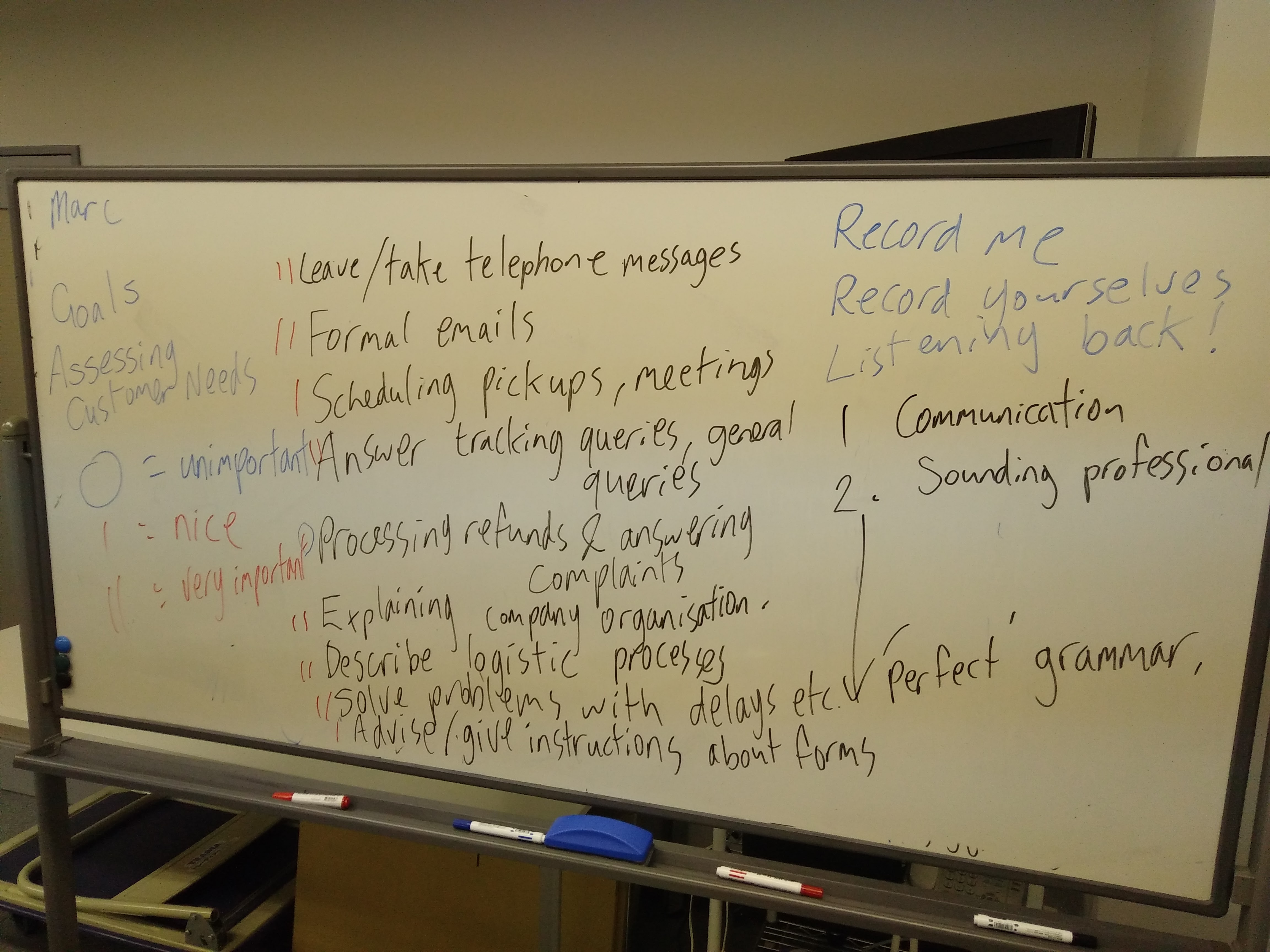

This board was based on my guesses what the students in this group might need based on knowledge that they work for a logistics services provider. I had the students in the group, of mixed level, rank the things that I chose according to how important they are.

It was interesting to find that answering complaints was not seen as important. I’ll leave this open for the rest of the course. It was also interesting to find that I don’t need to prioritise simple scheduling very highly. This means I’ll conflate the scheduling and queries lessons, with a bit of wriggle room by adding other things and renegotiating the syllabus again.

I leave one slot at the end for review or covering what crops up and then this is our syllabus for the rest of our 10-hour course. If you have any other ideas, feel free to share them in the comments.

What happened on the #ELTwhiteboard?

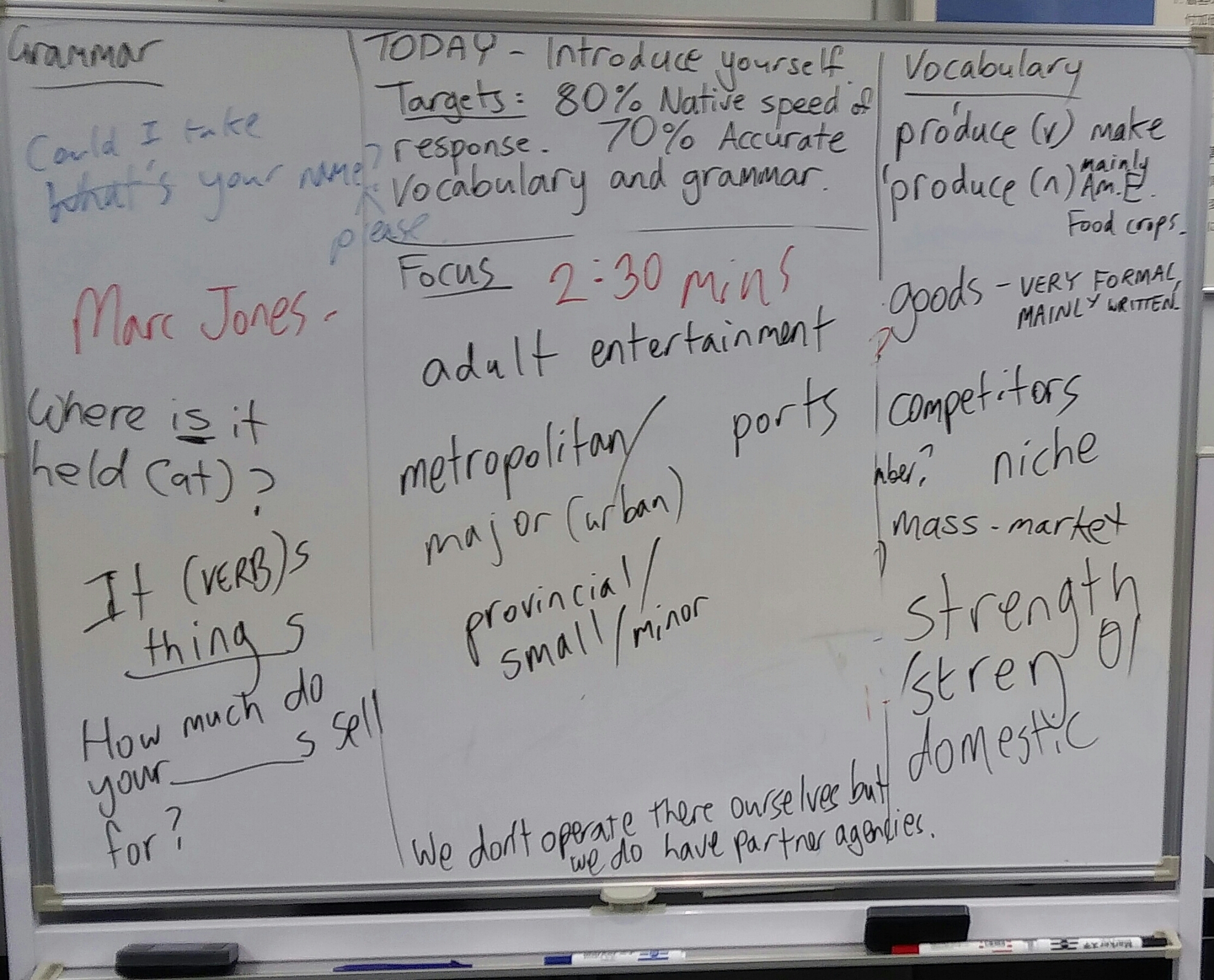

This whiteboard was for the second lesson of a course I am teaching based on Business Result Pre-Intermediate. The learners are six men at a logistics company.

The flow

Check homework from the Practice File (gap fills for vocabulary review).

First up was a game at the end of the chapter based on questions and answers. It gave me a chance to check question formation and adjacency pairs (speech acts that go together).

I was going to move on to ‘eavesdrop’ upon the listening on the previous page and transcribe the conversation with half the class transcribing the man and half transcribing the woman. I thought that the game went on too long to do the textbook listening so I moved on to the speaking activity.

The speaking activity was the task at the top of the board:Introduce yourself; Targets: 80% native speed of response, 70% accurate vocabulary and grammar. They had to introduce their company, too. Matthew asked why I chose these targets. I figure that an introduction is really easy but an introduction with parameters close to what would be acceptable on business, generally, would be closer to the ‘real world’ and encourage more involvement than a task with no parameters.

Kamila asked how I measure the speed. Basically, I wait till the preceding utterance finishes, mentally answer and count two beats from my point of answering. It sounds harder than it is.

How I set it up was in threes, too talk one transcribes the first speaker only. This was to build accuracy in the first speaker. I read about it in this article by Skehan and Foster. In the article, learners transcribed themselves but in this risk they transcribed each other. Conversations carried on for around seven minutes. I followed up with a focus on form. These were mainly about vocabulary or body language and a little bit on question formation with final prepositions. Advice was given based on the transcription and then the task was repeated. I then followed with pairs repeating a similar task but with a 2 min 30 sec time limit. The companies they chose to talk about were all fictionalised, hence ‘adult entertainment’. Homework set was a gap fill with ‘you’ or ‘I’ in questions.

It went well, particularly with the weaker students in the class. Some things I wish I’d done were getting the students to record each other in pairs then transcribe themselves. This ended up being the end of the next lesson (make a podcast section to give an introduction to your company) and homework (transcribe yourself, noting mistakes or things you would change if you did it again). Overall the lesson was quite good but I still am not totally satisfied. Maybe this is because I am still trying to figure out my rapport and how we gel. Maybe I feel it was a bit repetitive, though it was kind of a fun time.

"Are you seriously going to do that?"

I’ve been experimenting with board games in the classroom, sometimes in a bit of an impromptu way.

“Seriously, Marc? Aren’t you anti-game?“

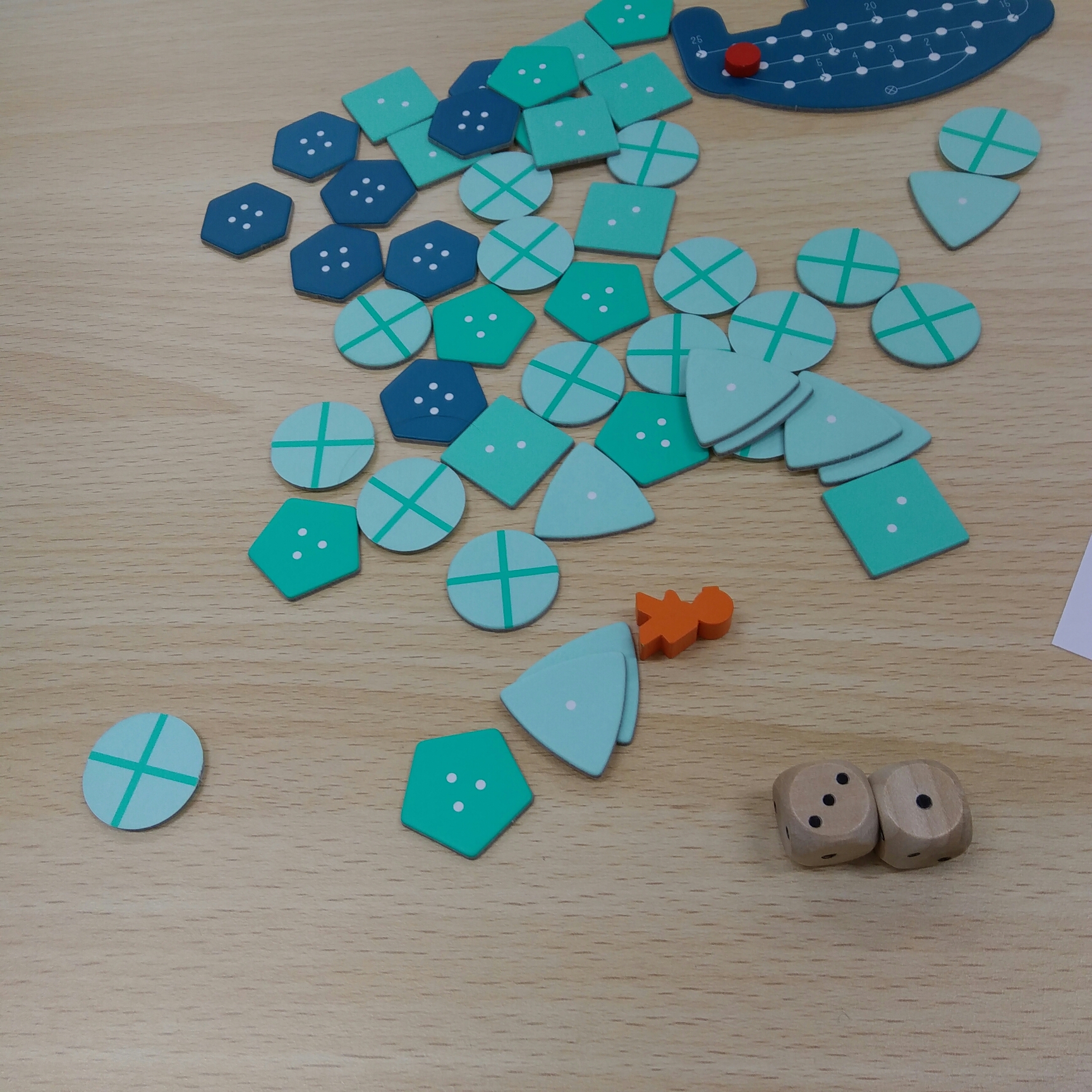

No, I’m not; I’m anti time wasting. I’m going to write a bit about things I’ve done with them below. Both, coincidentally, are by Oink Games. They are pocket sized, due to the boards being made up of chips. Both games require collaboration as well as competition, with shifts between both states.

Troll

This is a game of guessing card values and ‘betting’ on the value in order to gain treasure. It’s simple and addictive. The game works by guessing the value of a Troll card only one player has seen and as a group being lower (or not being the individual or one of a couple of individuals that takes the total over the Troll card value) in order to win gems.

I’ve played with children in small groups and in a big university class using teams, and this has tended to work well to encourage English use by penalising unnecessary Japanese use with a one-gem penalty. There’s a tendency to play risky but that’s the fun of the game. There’s negotiation among groups, as well as explanations of betting strategies.

Deep Sea Adventure

This is Troll with movement and is difficult to win points from without a bit of restraint and cooperation.

You go around the board as a diver collecting treasure but there’s an air ration, you only know the approximate value of the treasure and carrying it reduces your own movement and also reduces the air for everyone. Because of the game complexity, there is inbuilt need for communication, like “You can’t move five. You need to go back two because of your treasure.” or “you forgot to move the air meter.” My favourite utterances were a very ladylike “Oh, shit!” and “Are you seriously going to do that?”

Never mind a deep sea adventure, it’s a deep adventure into stuff students never say to one another.

Further reading

Rose Bard’s blog posts tagged with game-based learning.

Japan Game Lab

Video – Using Padlet with your learners

I had to do a formative assessment on my Using Technology and Corpora unit of my MA at University of Portsmouth. I couldn’t pick a technology that I was going to write about for one of my marked assessments so here is a bit about Padlet.

New Post Elsewhere

So, in spite of feeling sick as a bleeding parrot today, I have good news and good stuff for you to read.

So, over at the ITDi blog, there is a new issue up on Error Correction 2.0, with posts by Chris Mares, John Pfordresher and me. Chris and John talk about meaningful things , making correction nice meaningful, setting goals and such. I get on my high horse about the lack of focus on form regarding pronunciation, pragmatics and discourse awareness/analysis.

Gritty Politti: Grit, Growth Mindset and Neoliberal Language Teaching

Over the summer, while everyone else was enjoying themselves I was ruing the day I decided to look at grit (Duckworth, 2007) for my Master’s dissertation. I decided it’s unworkable so you get to read about it here.

What is Grit?

Grit is so difficult to define that it takes Duckworth (2016) the best part of a book to describe it adequately. Grit is the orientation of short-term goals toward one’s passions and long-term goals. It has also now mutated, taking on Dweck’s (1996) Growth Mindset, Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) Flow, Ericsson and Pool’s (2016) Deliberate Practice and become a behemoth. One is left with the impression that only Duckworth truly understands what she means by the term ‘grit’. Grit has also been criticised for not being substantially different to conscientiousness (Kamenetz, 2016). Even Duckworth and Quinn (2009) acknowledge that:

Grit is similar to one Conscientiousness facet in particular, achievement striving, which is measured with items such as “I’m something of a ‘workaholic”’ and “I strive for excellence in everything I do” (Costa & McCrae, 1992a). We believe grit is distinct from achievement striving in grit’s emphasis on long-term goals and persistence in the face of setbacks. However, further research is needed to determine the relationships between grit and other facets of Big Five Conscientiousness.

(Duckworth and Quinn, 2009, p. 173.)

Grit does appear to be lauded, particularly in the USA, for being a commonsense approach to teaching and learning. I do not think this is a good thing. The Grit Score, a short, subjective, Likert-scaled questionnaire, is being used by teachers and learners to assess learners’ grit. One problem here is the weight of the scoring and the disparity between teachers’ and learners’ perceptions. When searching the literature I found nothing. The fact that grit is being used as a magic bullet for the school system’s ills is also worrisome when one might consider the least advantaged actually attending school being a gritty act in itself. Yet, it is these children with poverty-caused cognitive overload (Mani et al, 2013) who will be labelled ‘least gritty’. Duckworth has bemoaned this, much like Frankenstein died at his own monster’s hand.

What negative effects are present? Well, we have teachers buying in to a new orthodoxy dressed up as science, where learners score themselves on how they tend to stick with certain habits. If the teacher is scoring them, so much the worse due to the likelihood of other factors making their way into the scores, such as warmth toward the learners of even empathy towards them. This grit then is used to blame learners or anything but the system, including curricula and syllabi. To me, grit is simply another tool for attacking the poor and the other. They might not be as gritty and it provides an excuse for not targetting financial resources in the classroom, such as teaching assistants, smaller class sizes or taking time to reflect on whole-school issues such as homework, which can effect some learners who may be primary carers. As Thomas (2013) states, “the dirty little secret behind ‘no excuses’ and ‘grit’ is that achievement is the result of slack, not grit.” However, if a lack of achievement can be put down to intrinsic factors within learners, then it provides grounds for ignoring them.

In language teaching, progress is known not to be cumulatively acquired (Lightbown, 1985) yet when language is assumed to be a skill acquired like the learning of facts, it may appear that there is not enough work being done by learners. In adult EFL, language learning may not be the most important part of a learner’s life; even in ESOL, when learners may have to adjust to living in a new country, community and culture, integrative motivation (Gardner & Lambert, 1972) may be lacking. To assume that everyone in a community shares the same values of utility is unwise; to assume language learners progress through stages at the same rate, with the same goals and motivational orientations is to ignore literature and evidence in the classroom.

All of this grit and Growth Mindset then, seems to lend itself to a laissez-faire attitude in the classroom, where what is taught is what is learned, with learners not progressing at the same rate somehow deficient and lacking gumption to catch up. This characterises the grammar syllabus of textbook ELT. However, if one eschewed that, and taught learners English as opposed to teaching English as a subject, one need not abide by or pay lip service to such ideas.

Grit, Growth Mindset and SLA

There is, so far, no research linking grit nor Growth Mindset and SLA. There is research linking motivation, particularly long-term motivation, to SLA. Dweck’s work thus far has looked at problem solving in puzzles yet it may prove to be useful in decreasing the effects of the frequently observed slump in intermediate-level language learners’ development (find and cite).

Dörnyei’s (2009) work on motivational selves has elements of learners orienting themselves toward long-term goals, expectations of others (such as schools, parents, bosses) and visualisation of what would be a possible worst-case scenario if they did not study. This is, in my opinion, compatible with grit but has the benefit of not being burdened with the unnecessary accoutrements of highly subjective data from questionnaires for groups; it is personal.

Duckworth (2016) also talks about building gritty communities yet what if one is alienated from the community of sees oneself as unintegrated in the target community? Seeing as grit is passion and perseverance for a goal, essentially personal, grit may not be the best paradigm to apply to the EFL/EAL/MFL classroom in a compulsory school setting.

Furthermore, developing grit may be an irrelevance. As Norton Peirce (1995) demonstrates in her work with ESL learners in Canada, learners are driven toward communication when needs arise, whether there may be negative affective factors in the immediate environment. This need can drive learning, with Martina, one of Norton Peirce’s learner-correspondents providing anecdotal evidence regarding problems in a part-time job:

In the evening I asked my daughter what I have to tell the customer. She said ‘May I help you’ and ‘pardon’ and ‘something else.’ When I tried first time to talk to two customers alone, they looked at me strangely, but I didn’t give up. I gave them everything they wanted and then I went looking for the girls and told them as usually only ‘cash’. They were surprised but they didn’t say anything.

(Norton Peirce, 1995, p.247)

Rather than nebulous ideas of how to teach or foster grit, self-regulative strategies (Oxford, 2013) could provide a jumping-off point for more effective self study or use of self-access facilities. Such strategies may foster greater motivation by providing learners with alternative ways of working than their current preferences.

One caveat here is that I think grit should be researched; I just don’t think there is a place for it to be brought into classes on a whim due to TED talks bringing a superficial informative lacquer to a few minutes of distraction.

If you disagree, by all means comment. I would love to know more, having spent ages with this.

References

Csikszentmihaly, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience”, New York: HarperCollins ebooks.

Denby, D. (June 21st, 2016) The Limits of Grit. The New Yorker. Retrieved August 22nd, 2016 from: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-limits-of-grit

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 Motivational Self System. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087-1101.

Duckworth, A. L. & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166-174.

Duckworth, A. L. (2016) Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House

Ericcson, A. & Pool, R. (2016) Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Harcourt.

Gardner, R. C. & Lambert, W. E. (1972) Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Kamenetz, A. (May 25th, 2016) MacArthur ‘Genius’ Angela Duckworth Responds To A New Critique Of Grit. Retrieved August 22nd, 2016 from: http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/05/25/479172868/angela-duckworth-responds-to-a-new-critique-of-grit

Lightbown, P. M. (1985) Great Expectations: Second language acquisition research and classroom teaching. Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 173-189.

Mani, A. et al (2013) Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science, 341,(6149), pp. 976-980

Norton Peirce, B. (1995) Social Identity, Investment and Language Learning. TESOL Quarterly 29/1: 9-31. In Seidlhofer, B (ed.) (2003) pp. 236-255. Oxford, New York: OUP.

Oxford, R (2013) Teaching and Researching Language Learning Strategies. Abingdon: Routledge.

Thomas, P. L. (November 10th, 2013) The Poverty Trap: Slack, Not Grit, Creates Achievement. Retrieved August 22nd, 2016 from: https://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com/2013/11/10/the-poverty-trap-slack-not-grit-creates-achievment/

Further Reading

Sheppard, R. (2016) Grit, Resilience and Conation in Adult Esol

Sheppard, R. (2016) Grit, Resilience and Conation in Adult Esol Part II

Seats for my seats

Seating plans: not the sexiest of topics to blog about but here we are after a 12-week action research cycle.

12 weeks, Marc?

12 weeks.

It’s not a big class but if you follow the Pareto principle that 85% of your problems come down to 15% of what’s on your plate then this class is my 15%.

The Learners

Gambit – a boy that can work well but cannot resist fussing about what others do.

Iceman – a boy that thinks he can’t do anything but I’d actually more able than he thinks.

Nightcrawler – a boy who is very literate and able but cannot sit still.

Angel – a boy who has sone kind of autistic spectrum disorder. Highly literate and communicative but also highly disruptive.

Cyclops – a quiet boy of medium ability.

Psylocke – a girl who is quite able but unwilling to try her best in case she falls short of her own benchmark based on others’ work.

Ms. Marvel – a girl who performs well in all skills. Confident but occasionally rushes work too much.

Some things that I found out quickly

The girls need to sit together else Psylocke won’t work.

Psylocke and Gambit distract each other.

Gambit and Angel irritate each other for fun but Angel will scream and occasionally lash out.

Cyclops cannot work near Angel, nor can Iceman. Iceman also cannot work near Nightcrawler.

None of the children like sitting alone very much and anyway, they need to practice speaking English as well as reading and writing.

So, what I did

I used Google Slides to plan my seating each lesson. Often I had one-week notice of absences. I logged any problems and/or changes. Sometimes I noticed huge problems that I had not anticipated, for example that Iceman will work near Gambit, a huge fusspot, but not near Nightcrawler who has a more relaxed temperament. It is not possible to seat Iceman near Cyclops due to Cyclops’ frequent absence.

Strangely, Nightcrawler and Angel make a good seating combination with Cyclops. Iceman and Gambit tend to relax one another, too. While I dislike the idea of boys and girls not sitting together, I am resigned to the girls need to sit together for affective reasons but bring them to work with boys when possible, often Nightcrawler and Cyclops or Angel.

Should this really have taken 12 weeks?

Well, it was more like nine and then three weeks to see if it was final. While ny final plan is not perfect it is good enough and the best possible solution for me and the children.

Real Alternatives Need Alacrity

It’s that old Corporate ELT is killing me slowly trope. Hang on to your hats, comrades, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

So, the coursebooks palaver came up again on Geoff Jordan’s blog. I have written on this before. The main change in my ideas is that instead of Dogme or Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) being the utopia we should all aim for, what is needed to get teachers to go with something better than a textbook is an alternative.

In the aforementioned post, Steve Brown said that what is needed is not any other kind of alternative but for teachers to take agency: choose what the materials are, or choose to choose with the learners, or whatnot. He is right, but I think there needs to be a bit of handholding to get there.

I’ve seen comments saying that it takes bloody ages to plan a TBLT lesson, and it does when you first start. Similarly CELTA-type lessons take bloody ages when you first start. No qualifications? Think to your first week on the job. Lesson plans took forever. Anything takes ages when you first start.You need to think about whether the initial time investment will pay off or not. You are reading a blog about teacher development, so ostensibly you are open to this seeing as you are reading this instead of playing video games or trolling Trump supporters.

So, let the handholding begin. Or the push to start.

What can I use instead of a coursebook?

Have a think (always a good idea) about what your learners need. Asking them is often a good idea, though teenagers might tell you they need about 3 hours in bed and that they need to do gap-fills of A1 vocab. They don’t. Assess. What can they do? What can’t they do? What aren’t you sure they can do? The answers to this should rarely be “They can’t do the past tense with regular verbs” or something. Maybe “They can’t answer questions about the weekend” is better. Cool. That is something we can chuck into the syllabus, if we think that our learners need this. If they don’t, don’t put it in. But why did you bother assessing it otherwise?

With all this information, you can create a syllabus/course. Sequencing it is a bit of a bugger because you want to think about complexity, what is likely needed toward the start and middle to get to the end, recycling language and such. However, you and your learners have control. This is not the kind of thing to put on a granite tablet. If it seems to need a bit of something else, do that.

But what do I do?

Teach the skills you need to teach. Potentially this is all four skills of reading, listening, writing and speaking. There are books about ways to teach these. You might want to browse Wayzgoose press. Also The Round minis range has some very interesting stuff, as does 52. If you get a copy of Teaching Unplugged, I find it useful.

You and your learners can then source texts from the internet (which a lot of textbooks do anyway so you are cutting out the middleman), edit for length (nice authentic language) or elaborate and spend longer with (that is, put in a gloss at the side or add clauses explaining the language). You can create your own, too, which sounds time consuming but might not be the pain in the arse you think it is. You can also put in some stuff that is rarely covered in textbooks like pronunciation and how to build listening skills, microlistening, and more (a bugbear of mine).

There are also lots of lesson plans on blogs (including here). If you have some good lessons that have worked for you, they might work for others, who can then adapt them. With a book, there are sunk costs and learners will want to plough through the lot if they have bought it. If you have a lesson plan to manipulate, without having sunken money into it bar some printer paper, you and your learners get more control and hopefully smething more suited to them than something chosen by an anonymous somebody in London or New York.

If I’m going to use texts, I might as well use a textbook!

You could, but think of all the pages of nonsense you have to skip. Think of the time spent with learners focussing on pointless vocabulary like ‘sextant’ (thanks Total English pre-intermediate). You have an idea. You know your learners, or at least the context. There is also a ton of stuff on the internet. May I point you to the Google Drive folder at the top of this blog. All the stuff in there is Creative Commons Licensed so you can change it if it isn’t perfect, copy it for your learners, and because I already made it and was going to anyway, it’s free. There is also Paul Walsh’s brill Decentralised Teaching and Learning. There are also ideas to use from Flashmob ELT.

So

You have these ideas to use, modify, whatever and put into timeslots. You can move them around. You have the means, now, if you decide it’s worth a go, stick with it for a few weeks at least, so you can get into the swing of it. If you like it, leave a comment. If you hate it and I’ve ruined your life (and be warned that not all supervisors, managers and even learners are open to this at first. Check, or at least be aware of this. If your learners say they want a book they might just mean they want materials provided and a plan from week to week) leave a comment.

If you think I’m talking nonsense, I’d seriously love you to leave a comment. Tell me why.

If you want help with this, I’m thinking of using Slack for a free (yes, really, at least initially) course type thing, say an experimental three weeks, where I help you sort out how to go about things (together; top-down isn’t how I do things), help with any teething troubles and so on. If you’re interested, contact me.

Well, Sunday night, eleven o’clock and 1000 words. I’m going to bed. Let’s sleep on it.

Your Secret Weapon

For loads of us in a (largely) monolingual EFL setting, there is an amazing resource available under our noses. I’d argue that a lot of people feel it’s a bit rude but I’m going to argue that rude or not, you get to maximize engagement in lessons through greater relevance and also at least partial schema activation.

Eavesdropping on your learners when they’re using L1.

If you can do it, this pays dividends. You get to give them what they are already thinking about but may not be able to do in English. For example, are people on your business class complaining on the phone? Can you help them do it in English, with appropriate language and pragmatic competence? How about the young learners talking about cartoons? Can they explain the plot, the characters or the appeal by involving you in a real conversation?

“What about the syllabus?” you might say.

Can you postpone that item? Work it in? Abandon it? I think we need to remember that syllabi are guides not commandments. And if we make things a bit closer to learners real lives they might want to work through that syllabus a bit more.