Some reflections.

Read Here be (Dungeons and) Dragons previous ‘chapters’: 1, 2, 3,

Read the future chapters 5, 6

Category: Reflection

Here be (Dungeons and) Dragons 3

The Wrath of the Math

“Huh?”

“Your points are 2 for taking a taxi, plus 1 if you told the driver where exactly to let you out. Then roll the D4. Add courage points to the D4. Divide them by 5.”

I should have seen this coming. How often do you see any English for arithmetic in EFL materials? Never. How many of these ladies at Ladies’ College of Suburban Tokyo (LCST) have played RPGs before? None, so the D4 terminology from the first lesson went in one ear and out the other of some students.

Next time I will provide a little bit of Focus on Form on the arithmetic terms and hope that our dining role plays go well, because other than the maths, it was a good lesson.

Read Here be (Dungeons and) Dragons previous ‘chapters’: 1, 2

Read the future chapters 4, 5, 6

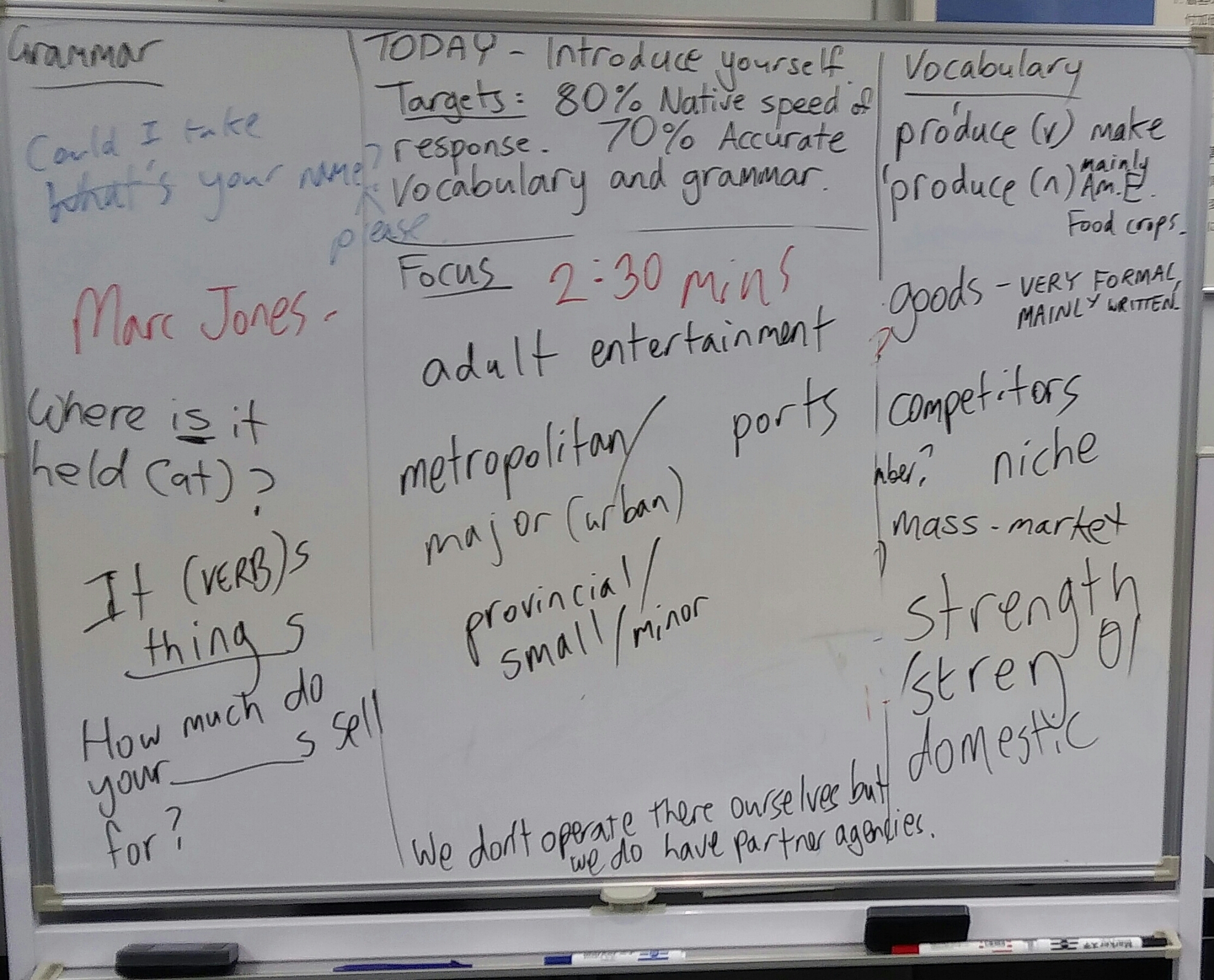

What happened on the #ELTwhiteboard?

This whiteboard was for the second lesson of a course I am teaching based on Business Result Pre-Intermediate. The learners are six men at a logistics company.

The flow

Check homework from the Practice File (gap fills for vocabulary review).

First up was a game at the end of the chapter based on questions and answers. It gave me a chance to check question formation and adjacency pairs (speech acts that go together).

I was going to move on to ‘eavesdrop’ upon the listening on the previous page and transcribe the conversation with half the class transcribing the man and half transcribing the woman. I thought that the game went on too long to do the textbook listening so I moved on to the speaking activity.

The speaking activity was the task at the top of the board:Introduce yourself; Targets: 80% native speed of response, 70% accurate vocabulary and grammar. They had to introduce their company, too. Matthew asked why I chose these targets. I figure that an introduction is really easy but an introduction with parameters close to what would be acceptable on business, generally, would be closer to the ‘real world’ and encourage more involvement than a task with no parameters.

Kamila asked how I measure the speed. Basically, I wait till the preceding utterance finishes, mentally answer and count two beats from my point of answering. It sounds harder than it is.

How I set it up was in threes, too talk one transcribes the first speaker only. This was to build accuracy in the first speaker. I read about it in this article by Skehan and Foster. In the article, learners transcribed themselves but in this risk they transcribed each other. Conversations carried on for around seven minutes. I followed up with a focus on form. These were mainly about vocabulary or body language and a little bit on question formation with final prepositions. Advice was given based on the transcription and then the task was repeated. I then followed with pairs repeating a similar task but with a 2 min 30 sec time limit. The companies they chose to talk about were all fictionalised, hence ‘adult entertainment’. Homework set was a gap fill with ‘you’ or ‘I’ in questions.

It went well, particularly with the weaker students in the class. Some things I wish I’d done were getting the students to record each other in pairs then transcribe themselves. This ended up being the end of the next lesson (make a podcast section to give an introduction to your company) and homework (transcribe yourself, noting mistakes or things you would change if you did it again). Overall the lesson was quite good but I still am not totally satisfied. Maybe this is because I am still trying to figure out my rapport and how we gel. Maybe I feel it was a bit repetitive, though it was kind of a fun time.

Seats for my seats

Seating plans: not the sexiest of topics to blog about but here we are after a 12-week action research cycle.

12 weeks, Marc?

12 weeks.

It’s not a big class but if you follow the Pareto principle that 85% of your problems come down to 15% of what’s on your plate then this class is my 15%.

The Learners

Gambit – a boy that can work well but cannot resist fussing about what others do.

Iceman – a boy that thinks he can’t do anything but I’d actually more able than he thinks.

Nightcrawler – a boy who is very literate and able but cannot sit still.

Angel – a boy who has sone kind of autistic spectrum disorder. Highly literate and communicative but also highly disruptive.

Cyclops – a quiet boy of medium ability.

Psylocke – a girl who is quite able but unwilling to try her best in case she falls short of her own benchmark based on others’ work.

Ms. Marvel – a girl who performs well in all skills. Confident but occasionally rushes work too much.

Some things that I found out quickly

The girls need to sit together else Psylocke won’t work.

Psylocke and Gambit distract each other.

Gambit and Angel irritate each other for fun but Angel will scream and occasionally lash out.

Cyclops cannot work near Angel, nor can Iceman. Iceman also cannot work near Nightcrawler.

None of the children like sitting alone very much and anyway, they need to practice speaking English as well as reading and writing.

So, what I did

I used Google Slides to plan my seating each lesson. Often I had one-week notice of absences. I logged any problems and/or changes. Sometimes I noticed huge problems that I had not anticipated, for example that Iceman will work near Gambit, a huge fusspot, but not near Nightcrawler who has a more relaxed temperament. It is not possible to seat Iceman near Cyclops due to Cyclops’ frequent absence.

Strangely, Nightcrawler and Angel make a good seating combination with Cyclops. Iceman and Gambit tend to relax one another, too. While I dislike the idea of boys and girls not sitting together, I am resigned to the girls need to sit together for affective reasons but bring them to work with boys when possible, often Nightcrawler and Cyclops or Angel.

Should this really have taken 12 weeks?

Well, it was more like nine and then three weeks to see if it was final. While ny final plan is not perfect it is good enough and the best possible solution for me and the children.

Every Little Thing The Reflex Does

I’m showing my age, I know.

I was just thinking earlier, about decision making in the classroom. There’s a brilliant diagram by Chaudron in one of my favourite books, Allwright & Bailey (1991?) Focus on the Language Classroom. CUP. It shows the multitude of decisions we have to make in our classrooms on the fly about error treatment. Add to these the decisions about whether to divert from the lesson plan and how to do it and then it’s an even larger number.

With all these decisions, how do we go about them in a principled way? I feel we do an awful lot based on reflexivity as opposed to reflection. I know that we build up our intuition as we log more classroom practice and think about what goes on but can any of us say every single one of our decisions is planned in advance?

So, the point: I wonder if we logged every reflexive decision and its outcome whether it would help to make better decisions more likely, sort of by step-by-step proceduralizing the metacognitive process (or thinking about what was a good decision and what was a bad decision and hoping that the remnants of this reflection will be accessible the next time you have a similar decision to make).

We can wing it every lesson but is it always the most effective to wing every stage of the lesson all the time? If you’ve done similar things, you can hopefully make similar successes more probable. It’s just making those seemingly more trivial decisions more principled because they might just have ramifications that we don’t anticipate. And as Duran Duran say, “Every little thing the reflex does leaves an answer with a question mark”. Flex-flex!

Mentoring is Brilliant

There is a ton written on mentoring as part of professional development. It seems like it’s pretty much a ‘good thing’ all the time, and I’m kind of tempted to go along with that because of one of the reasons I’ll give below.

- You get to see another approach to the job

- You get another point of view

- Avoiding too much introspection

- Bad is Good

Everyone has preconceived ideas about teaching when they start, based on the teachers that taught them. Just as not everyone has the same experiences, not everyone has the same approach.

Some mentors will be great about this and understand that not everyone needs to do the same thing to get the intended results. Some mentors won’t be great about it and will insist you should teach their way.

You can learn a lot about your own teaching by trying to teach according to someone else’s approach. Even the bits that you might not have attributed merit toward may have hidden utility in the classroom.

This is better the more mentors you have. Behaviour issues in the classroom? There are endless possible solutions. Experienced mentors probably have several techniques to counteract negative behaviour. And that’s just one example.

Reflective practice is something I think is beneficial but too much reflection is worthless. Think of a mirror maze as a metaphor. If you are part of a mentoring relationship you get used to making sure your thinking and rationale are clear. People are working, and while most mentors and mentees are positive, if you get ready for a meeting with a half-baked idea people will show you that they think their time is being wasted. You get forced into habits of rigour.

If your mentor is dreadful you get to see them as a cautionary tale. You get used to assessing what authoritative voices say and filtering it (which is excellent practice for books by both ELT and general Education gurus).

If your mentee is bloody awful, you get the chance to really take a hand in helping them develop and can take a hand in stopping unproductive practices through explaining better ones (and perhaps demonstrating them, too).

Finding mentors and mentees

I have a great mentor at one of my workplaces, in that he is very practical, does lots of professional development but not much theory. We get to duel a little bit on the theoretical applications I might espouse, and it helps me refine and reflect upon my beliefs.

I also have other mentors on Twitter, miles away working in different settings but still supporting me, feeding ideas and even just lending a virtual ear when I need to vent.

Mentees sort of drift, due to the peripatetic nature of my working life, but basically I have a couple of mentees, one a very new teacher who needs to go with the flow more (which leads me to practice what I preach and not obsess over minuscule annoyances at the stupidest workplace) and another who has such abundant ideas but needs a push to be bolder or just reassured they are on the right track (and who has helped with a few lesson ideas and made me justify choices leading to more confidence in my own teaching).

You might want to check out the iTDI blog mentoring issues, Giving Back and Giving Back II, too.

Hopefully this has helped you think about what mentoring is (or can be). Any more ideas?

Winging It – Not a skill to be sniffed at

First up, let me make it absolutely clear – planning lessons, at least in your head and preferably a few jottings on paper, before you go into the classroom is highly recommended. Even with Dogme you’re thinking about your likely reactions and you probably know the learners so have a good idea of needs. However, all of us at some point, and quite often for a few of us, have to wing a lesson because of any of the following reasons:

We are covering a lesson at the last minute with no cover work left by the regular teacher.

There are unexpected occurrences that mean the planned lesson (or planned tea break) can’t happen and you need to do something, preferably with a quick decision.

IT has failed or materials are not available.

What can you do?

If you have a textbook, you can do one of the other units. This will likely be a choice of nothing or the worst unit in there. Pay lip service to it by generating vocabulary from pictures in there and then set up a task or activity related to that theme. My favourite lesson when I worked for a rubbish school was an At the Airport unit which became a roleplay with feelings and personality eccentricities. I did this by selecting the only lesson a last-minute addition to the lesson hadn’t already studied.

Otherwise, you can Dogme your lesson and start a conversation. Think at each stage, what can the learners do? What can they almost do? The almost stage is great – try something that will enable this to be further developed.

Language?

This gives you the ideal opportunity to focus on weak points of language that manifest themselves in learner output. It could be grammar but it doesn’t have to be. How often do you think students get help with pronunciation? How about use of reference to sound more natural and concise? Don’t just pick a random grammar point for the sake of it. It’s nice to have gone in winging it and come out having taught something a bit unusual. I’d also say, don’t be afraid of going wide with the language focus in your lesson instead of deep with one thing. Students like it and you can always suggest further study on that point for homework (such as finding more examples online or from a newspaper or something).

Reflect

The old chestnut is, the best lessons we teach are ones we didn’t plan. Write it down: what would you do differently? What worked well? Could you substitute any part into another lesson plan to make it better? If it was without a book, your students might appreciate time to talk with each other. You’ve had a really good opportunity to teach reacting to students and not worrying about keeping to a plan. It might have been a bit rough but what were the redeeming features?

Any other tips or concerns for winging it? Leave them in the comments.

Emergent Language and Your Learners

Rant alert.

It has been some time now since I finished my DipTESOL and since I was a guest TEFLologist. This post is about Dogme, dogmatism and possibly dogged determination and the sheer bloody-mindedness involved. My tutors on the Diploma advised me against Dogme because they knew it would be very difficult to meet the assessment criteria. This post is in no way intended to be a criticism of them.

I failed a Dogme lesson in my DipTESOL teaching practice. I had been forewarned that Dogme lessons would be difficult to meet the assessment criteria with. I believe, from my experience as a language teacher and a language learner that emergent language (Meddings & Thornbury (2009, Part A, 3), that is scaffolded language based on direct need as opposed to arbitrary grammar or lexical sets based on level of complexity and (possibly blind) estimation of being ready. Having more lessons to teach than most of my tutor group, I decided I could risk it. I went in to the lesson, focussed on learner-centredness, and a ton of paper to take notes of learners’ problematic utterances.

There was discussion, there was error treatment, there was a bit of tidying up of learner language with some drills where needed.

The lesson didn’t pass. Reading between the lines, ‘Lack of language focus’ means ‘Don’t just scaffold several things seen to need work; pick one or two to focus on and then we can tick the box.’ Even with a Task-Based lesson as my externally assessed lesson, using emergent language caused a lower grading than might have been attained with a preselected grammar point. (Aside: I had predicted high numbers to be problematic and did a bit of a focus on that.) The problem that arises here is that emergent language for only a couple (or at best, a few) is looked at in depth. Better than an arbitrary choice of a grammar structure but why not look at more in less depth, assigning further investigation as homework? Those who need the assistance will surely notice correction and further examples.

Regular readers will know that I’m no fan of teaching grammar points (or Grammar McNuggets [Thornbury, 2010]). When I gave my presentation on the lack of application of SLA in Eikaiwa (language schools) and ALT industries in Japan, I had a really pertinent question. “How can you teach language based on emergent language?”

You can group your learners, set them differentiated tasks, after giving language input based on your notes of learner language. This is not something I did in my DipTESOL teaching practice but it is something I have done in my university classroom. It doesn’t have to be grammar; it could be vocabulary or even discourse-level work.

Be aware, though, that some learners do not see the value in using what they have said. They expect a grammar point, whether that is good for them or not. In that case, I suppose you can only make the best of things and give your students what they want. I would say, in a probably overly patrician way, that you might want to sneak in something they need, much like hiding peas and carrots in the mashed potatoes.

I think the big problem in using emergent language in your teaching is that it can’t be planned as such. It can be estimated and you’ll be right or wrong, or it can be saved for the next lesson but at that point it may not be as fresh in your learners’ minds and then less readily brought into their interlanguage, as defined by Selinker (1972, in Selinker, 1988). It means being ready to be reactive. It might not be the best way to get boxes ticked in an assessment.

References

Meddings, L & Thornbury, T (2009) Teaching Unplugged. Peaslake: Delta.

Selinker, L (1988) Papers in Interlanguage, Occasional Papers No. 44 (http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED321549)

TEFLology (2015) Episode 35: Dogme on the Diploma, Dave Willis and the Lingua Walkout (http://teflology-podcast.com/2015/11/25/episode-35-dogme-on-the-diploma-dave-willis-and-the-lingua-walkout/)

Thornbury, S (2010) G is for Grammar McNuggets (https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2010/09/18/g-is-for-grammar-mcnuggets/)

Advancing to What Exactly?

I was reading a post by Geoffrey Jordan about whether he should accept an advanced learner for an immersion course, and it got me thinking about the same topic, rather deeply.

I believe in learner-centred teaching, learner autonomy. None of this is astoundingly new, nor is it unorthodox. Some of the hackles raised by the people opposed to it may be that it is tree-hugging hippy crap or they’re tired of people who haven’t seen the inside of a classroom in ten years telling them how they should be teaching. Some of it is “common sense” or “just good teaching”. However, I do think that learners could do a lot more on their own: checking vocabulary, listening practice, reading for pleasure, etc.

In the language school I used to work at, there was also a debate about whether learners could ‘graduate’ from the school. The sales staff thought not; the teachers thought so. The sales staff get money for bums on seats whereas the teachers get the feelgood glow from thoughts of helping learners attain intended proficiency levels. It’s not that simple, though. I do know of organisations that have refused advanced-level students to join classes, though this is more to do with very-advanced-level students intimidating the upper-intermediate learners. I do not know of any that have done so for reasons of fostering learner autonomy. A lot of teachers don’t like to have their learners in too low a level. What if no level is high enough? Other teachers don’t want their students to be in over their head. In that case, how come they don’t have the tools to cope with autonomy at advanced level?

Geoff’s conundrum is whether his learner would benefit (or benefit enough) from the course. In an ideal world he might just curl up with a book, a video, put the radio on, talk to somebody online or write to a friend. However, I do mean ‘in an ideal world’; his learner might not actually be motivated to do it without a teacher there to motivate him. I feel that some of my most motivated learners would read and listen widely even if I didn’t moan at motivate them to.

I see my role as having my learners get to the point where they no longer need me. However, this leads to the issue of who decides. Should the teacher or the learner ultimately decided when they are ready for autonomy? (There is an interesting article by Sara Cotterall about readiness for learner autonomy [PDF].) I hate to feel like I’m saying there’s nothing to learn, but then teaching does not necessarily equate to learning.

Of course, it’s in no teacher’s best interests to turn down money from a willing student. I tend to wonder whether it’s the morality at play; that even if we are not wrong, that we feel bad for taking money when the teaching sometimes feels less intensive or there is less visible, near-immediate learning taking place.

Cottage Industry as CPD

Working as a teacher gives you opportunities to have interesting conversations with people and have fun with language. Sometimes, though, you just feel stuck in a rut and want to change things. This could be the start of something beautiful.

You can look at what you might make better instead of having a moan. Are your materials crap? Make some. Turn yourself into a cottage industry within a larger industry. You might learn a bit about what makes good materials. If you do decide to make your own materials, I recommend Powerpoint as opposed to Word, because you can get your layout aligned more easily. Test your materials and refine them (Eric Ries lays out this process in The Lean Startup as Minimum Viable Product [and you don’t have to sell your products for money. Kudos is currency sometimes]).

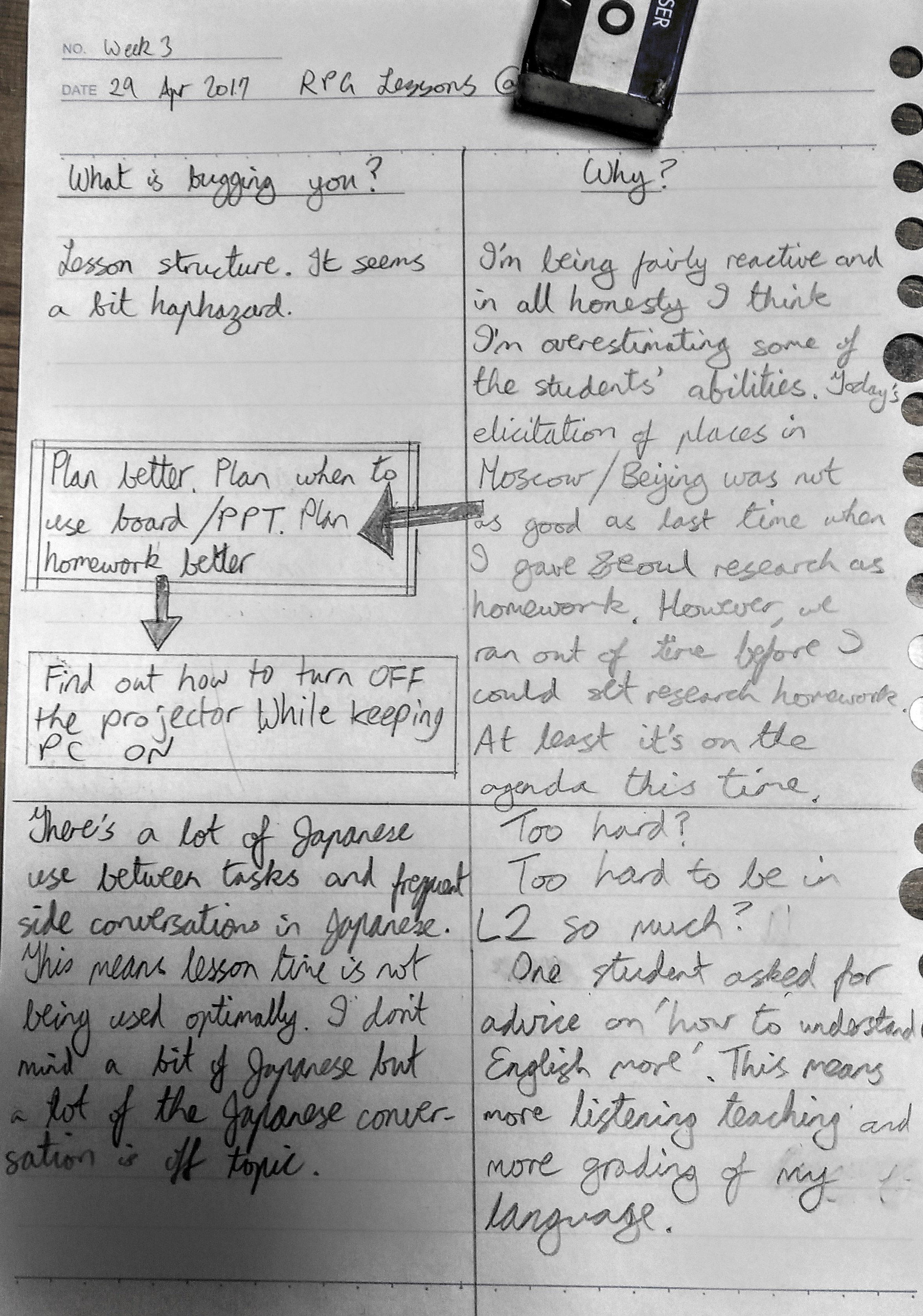

You might also do a bit of action research. There is a lot of high-faluting imagery about this but what it comes down to is this:

- Have a think about something you want to change or want to understand the effect of.

- Think of one thing to change in your practice so you can observe it.

- Record it.

- Keep doing it for a bit so you know if you are fluking it or whatnot.

- Reflect.

- Maybe have another go.

This might lead you to new ways of working that are better for you. I would think so. Otherwise you might have other like-minded souls join you. However, some see things like this as too much work, rocking the boat or otherwise undesirable. Do it for yourself, not for gratification from others, else you will never see it through.

If you have a blog, why not show your work?

Stuff I’m working on at the moment is a beefed-up version of my TBLT board, and simple materials that can be used easily and widely for useful tasks. This will be coming up soon. But not very soon, so don’t hold your breath. I’m talking at least Summer.