With people from Mastodon, I have joined a Radical Pedagogy reading group. It’s an area that I’ve got gaps in my knowledge about, despite my education in a post-structuralist, Marxist-sympathetic BA Film and Media programme.

Freire is somebody that I’d read bits by, and I had read bits from Pedagogy of the Oppressed before, but never the whole lot. So, time to put that right.

One of the main impressions that the book left me with were:

- This doesn’t even nearly go far enough! It seems a bit weak to be saying ‘listen to the people and learn from them’. Maybe it’s not so radical nowadays. Maybe I am too experienced now? Is reading The Pedagogy of the Oppressed for the first time after teaching for 17 years like reading The Catcher in the Rye for the first time at 40 years old? (Thanks Maloki!)

- How patrician is this? At points he makes the right noises about being at one with the workers and then at other points sounds fairly outside looking in.

- Quoting Mao, Castro and Guevara. In the 1970s. I can possibly accept that the full horrors of the Cuban regime might not have come to light. However, Maoism caused the displacement of loads of Chinese people fleeing the so-called Cultural Revolution.

That said, there are some good bits. Like this:

“No pedagogy which is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed must be their own example in the struggle for their redemption.”

(p. 54)

But it gets marred a bit by some of the patrician tone which rears up in Chapters 3 and 4.

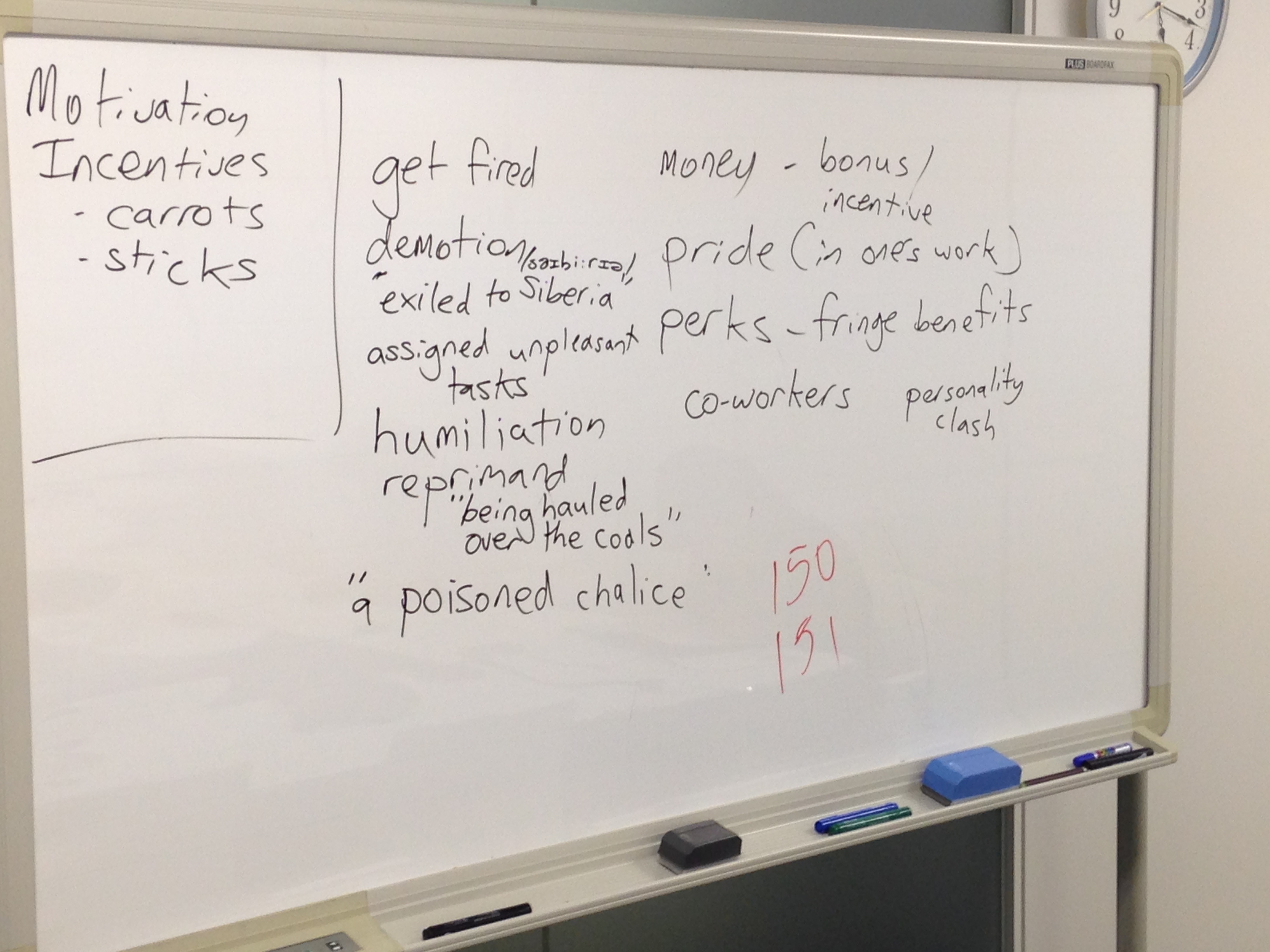

The way that people can make quite poor choices in their learning also comes up.

“at a certain point in their existential experience the oppressed feel an irresistible attraction towards the oppressors and their way of life. Sharing this way of life becomes an overpowering aspiration.”

(p. 62)

I think this echoes a lot of what happens with native-speakerism and native-speaker framing.

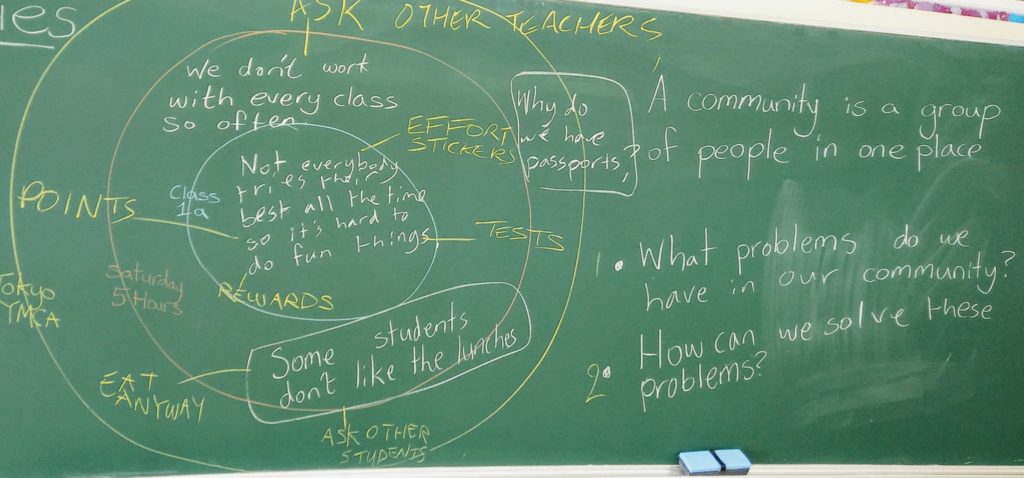

“Problem-posing education is revolutionary futurity. Hence it is prophetic (and, as such, hopeful).”

(p.84)

Contrast with the whole ‘we are preparing our children for the 65% of jobs that do not exist yet’ palaver. Is Freire’s futurity one that we predict assuredly, or one we gamble upon? I believe it requires information from learners, stakeholders and circumstances/context, to make a reasonable prediction.

And a paragraph that made me just think ‘this is commercial ELT all over’ was:

“For cultural invasion to succeed, it is essential that those invaded become convinced of their intrinsic inferiority. Since everything has its opposite, if those who are invaded consider themselves inferior, they must necessarily recognize the superiority of the invaders. The values of the latter thereby become the pattern for the former. The more invasion is accentuated and those invaded are alienated from the spirit of their own culture and from themselves, the more the latter want to be like the invaders: to walk like them, dress like them, talk like them.”

(p. 153)

The whole white-people, implicitly and often even explicitly cis, hetero, middle-class nature of coursebooks and language school marketing materials. I mean, this was being theorised best part of 50 years ago and still it manifests itself! Is an anti-cultural-imperialist ELT a lost cause?

So, I didn’t love the book. It might be a victim of hype, or just hasn’t aged well, or maybe I just have a ‘wrong’ ideology. However, I am looking forward to the next book for the group, whatever it may be.