Over the last couple of weeks, a lot of my communication online and offline has been about English language education and the status, stage and purpose it occupies, for teachers as well as students. There are the usual gripes of coursebooks, which I am not going to get into here because I have looked at it before (on more than one occasion), and also the state of the industry/profession and the definitions of ELT, (T)EFL, (T)ESL, (T)ESOL (and Steve tweeted that maybe this is not actually the case now).

So, a bit of background out of the way, on to Mordor!

Us and Them

Most English teachers are, like most people, nice and just trying to go about their day. I’m not going to talk about the outliers who are just unpleasant. This is for the rest of us, and I’m going to talk about a few types of people and it gets political, actually. Sorry, but I’m not sorry.

English teachers generally tend to be a bit bleeding heart. English teachers generally need money to feed themselves and do nice stuff. We can kid ourselves that we are helping make the world a better place. However, why not indulge me and just consider the following questions.

- How much do we dripfeed the subliminal message that English makes the world go round and anything else just is a bit substandard?

- We need work, and if Chain Language School can offer enough work to ensure one doesn’t end up homeless even though they drive down wages by aggressive undercutting, is this a wise choice?

- Do you teach people or content? I’m not even talking about methodology here.

- Are we, as teachers, being enabled to use a book in a pedagogically sound way and being enabled to deliver content in a standardised way?

- Are we thinking about how to enable language acquisition to take place?

- Are we thinking about how to enable acquired language to be used to perform tasks or even speech acts appropriately?

- Are we given time and resources to provide the best teaching possible?

While a lot of these questions have answers that seem obvious, I am going to say that a lot of us say one thing and do another – and I am holding my hands up here and saying I am not perfect but I try to be good. Eating requires money and so on. Luckily, I don’t require a fast car or designer clothes to feel good about myself. I do have a child and this means the earning of money and the teaching of language.

The problem is that other forces, basically capitalism/neoliberalism manipulate the environment and how easy it is to make wise choices all the time. I’ll go out on a limb and say that several of the larger publishers even obfuscate what a wise choice would even be, because it would actually cause the teachers and administrators who buy/order books to see that buying more books that are pedagogically unsound is, well, unsound and so they would stop ordering and the publisher would cease to exist.

The differences between us

Look, I don’t want to be a snob (actually, even an anti-snob), nor do I want to be telling anybody how to live their life, but if people can’t actually see what’s at the end of their noses when somebody is pointing it out, I would have to say they’re wilfully blind.

- Deskilled teachers.

- Unskilled ‘teachers’.

- Edutainment.

- Marketisation of standardised tests of reading and listening used as a benchmark for communicative skills.

- Use of a standardised test to assume someone can do a job when there are no similar instances of domain-specific language.

- Book as syllabus.

- Book as content.

- E-‘learning’ of multiple-choice questions.

- Making everything about jobs rather than edification.

- Making everything about financial return for companies rather than value for money for students, teachers and education providers.

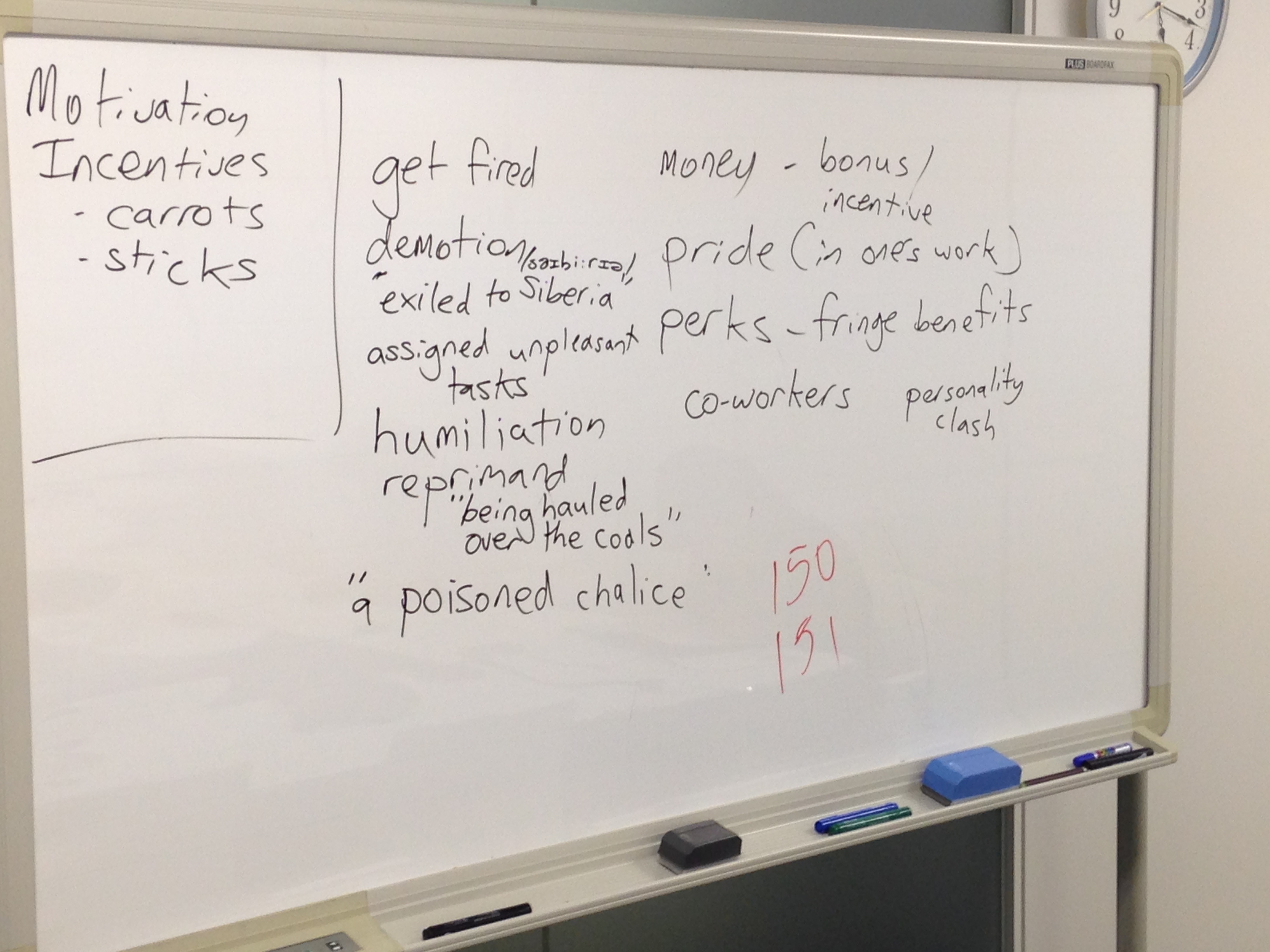

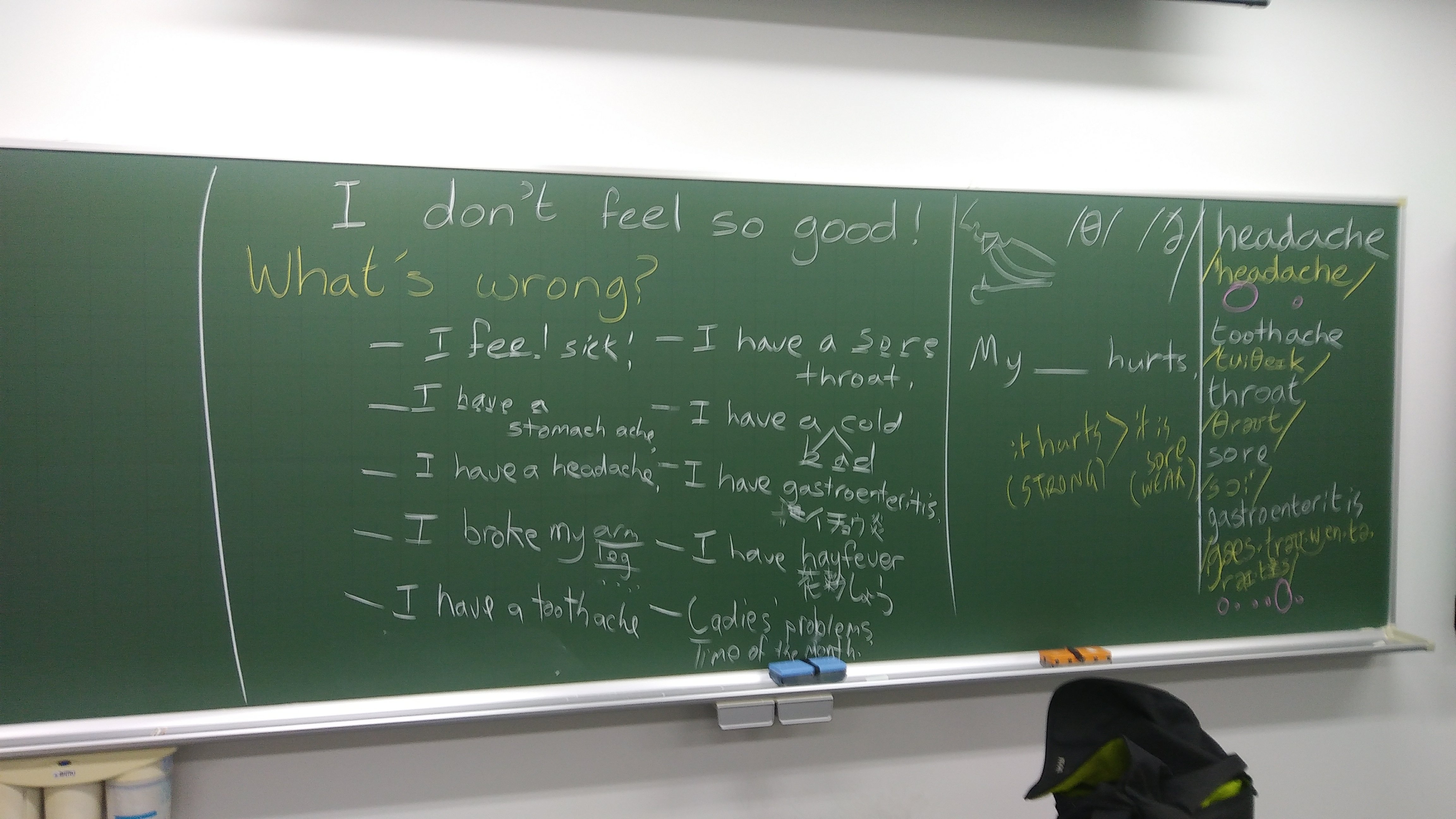

We have a whole culture of spending a month to do a course to get a credential to prove you can be in a classroom and not have chaos ensue. We have companies who will take bachelor’s degree holders and have them provide lessons and have essentially the same credential experience without the credential. This is seen as enough. This is seen as the terminal qualification, the furthest one needs to go, in a lot of commercial language education providers.

We have a culture of needing to move out of the classroom to make adequate money to raise a family. Time in the classroom is not rewarded. Unfortunately, this culture is being passed from commercial entities to schools and colleges. Teaching ‘only’ requires navigating content, providing it, and are we back at audiolingualism yet, because we have presentation of language, practice with behaviourist gap-fills and behaviourist CALL/MALL? Nothing moves on or needs to move on if money can be made.

We have experts and ‘experts’. We have people who have looked at learning, looked at other people’s studies of learning and tried to apply the findings. We also have people who have paid lip service to these studies, dismissed them because they don’t fit with what is convenient or what they have always done. We have providers of continuing professional development who are providing merely orientations to their products.

By any means necessary

You can’t fight cash fluid market leaders with merely a better lesson. You cannot provide lessons to everyone. What can be done is to show what you are actually doing. If you do good work, show it. Somebody might nick your idea. This is actually a good thing because this will raise standards. I mean, yeah, get pissed off that the idea thief didn’t do the legwork to be original or even helpful, but if the idea disperses, good stuff comes. If you have a better alternative to coursebook ELT, you need to have a tangible version of this. People are busy and they need, sadly, to just be able to print something, see what to do, and do it (I am working on something about this).

Standing on the other side of the line

I think we, as the critical wing of English teaching, need to define ourselves in opposition to the dominant idea and practice in English teaching, which usually gets called ELT (I’d say ELT Research Bites is far out of this dominant idea). As nothing bloody changes for the better and Silicon Valley gets lionised in society more and more with poor-quality MALL becoming more prevalent, we need to draw the line to stop frankly awful quality pedagogy in language education becoming the norm, stopping poor pedagogy being acceptable in language teaching, and stopping the rot. You can’t do this by just accepting it, doing your own thing and hoping that others will somehow see what you are doing and do it. We need to speak about the poor side of stuff when it dominates. We can see the rubbish – it’s in every bookshop, every catalogue you get sent, every commercial presentation at a conference, every pointless app that gets recommended for students.

Show your good stuff. The good will out. Now let’s change things.

I’m writing this in snatched time while I’m walking to the supermarket. To be honest this year hasn’t been one of the best years for me, particularly my mental health. However, I managed to find the Holy Grail of a full-time job to start in 2019 though it has made me a lot more aware of the precarious nature of English language teaching more of which later.

I’m writing this in snatched time while I’m walking to the supermarket. To be honest this year hasn’t been one of the best years for me, particularly my mental health. However, I managed to find the Holy Grail of a full-time job to start in 2019 though it has made me a lot more aware of the precarious nature of English language teaching more of which later.