Happy New Year everyone. I am not going to do a yearly reflection because 2017 was a mixed bag and quite stressful.

On ELT Twitter and across ELT blogs there is some murmurings about research (usually on teacher beliefs) and hidden in a paragraph somewhere is a mention that this is in preparation for an IATEFL talk. This got me wondering about whether people would do such research if they didn’t have a conference proposal accepted. I suppose what I am trying to say is that if you had a rejection, at least one person thinks your idea matters (you), and the big conferences are not the only way to get such research out. Local teachers associations and chapters of them want speakers at meetings. If that doesn’t work, it might even be useful as a magazine article or blog post. For all the hand wringing about teacher research, it would be a good idea to follow through on a good idea without needing a conference committee to say something is a good idea.

Speaking of conferences, how many of them are affordable for people without research budgets? Seriously! JALT’s conference is quite expensive for four days (without considering the fact that most working teachers in Japan can’t take Friday and Monday off). IATEFL is expensive, too. Pretty much anything with ‘International’ in the name of the conference is expensive. When ExcitELT came to Tokyo, it was cheap. There were no tote bags filled with university press-branded pens or anything but that’s a weird thing to want from a conference. Could we have more for less? Easy, if commercial entities don’t join in and demand their perks.

I suppose what I am saying is ELT doesn’t have to be a spending spree. What the CPD could be is a lot cheaper, a lot more grassroots and perhaps more relevant. Let’s see more of this from this year.

Category: Uncategorized

Teaching Strategy Chains for Listening (or not)

This is a small research project I did for my MA. It was my lowest mark on the course and I totally tried to do more than was feasible. I will address the limitations below.

Teaching strategies

An approach to using strategies in listening isn’t new, although there is more to it than the advice given to new TOEIC teachers of “Get them to predict based on what they hear and then think about the gist.” What interested me was whether the strategy chains that learners build up, according to Rebecca Oxford (2011) could be instructed.

I put together a class at the local community hall for 6 weeks, with 7 women. The first class let me see the strategies that the learners were already using and give a questionnaire (the MALQ by Vandergrift et al., 2006). The last class involved no instruction of the strategy chain but allowed me to see whether it was being used. Most used a few simple strategies. I derived a chain of potentially useful strategies based upon learners’ answers to the MALQ. The class was a massive mix of levels, from A1 to B2 on the CEFR. I used a mix of authentic texts (reality television) and inauthentic texts (from elllo.org). First I used one text to teach the strategy chain. Learners listened twice and transcribed what they understood from the text in English or Japanese. They wrote what strategies they used in English or Japanese.

The chain

I derived the following chain for instruction: schema activation (through focused thought or speaking to other learners about the topic), plan how to listen based upon their schema activation, relax in order to reduce cognitive load issues and regain focus when attention has been lost. The reasons for this particular chain was that the learners reported little use of these strategies in their listening yet I believed that the learners would benefit from them, particularly the relaxing and refocusing.

So, what happened?

Well, all the learners went along happily with the teaching and said they used the strategy chain in weeks 2-5. In week 6, the assessment week, not a single learner reported use of the chain.

Now, this is not the end of the world. It showed me that teaching is just teaching. Whether learners decide to do something in a classroom is another thing entirely. You cannot force a way of working onto someone. It also comes down to comfort and experience. For some of the learners, they were quite proficient in communication but claimed to be uncomfortable with listening. I used schema activation in the chain and perhaps this was something that they did unconsciously. For the lower-proficiency learners, perhaps the relaxing and refocusing needed more time to be practiced effectively. Whatever the case, strategies are used, in tandem with one another, but perhaps rely more upon learner evaluation of the strategies’ value in combination than teacher evaluation.

Another aspect of the course was that it was 6 weeks which was all the time fast was feasible for me after handing out leaflets on the street and asking friends to share on Facebook (when I was on there). Potentially, with a longer course it might have resulted in learners using this chain in the assessment week. It might not have, and I am going to say that it appears unlikely. Still, it’s good to know what is unlikely to work, isn’t it?

In all likelihood it appears that teaching strategies helps learners, but the chain of strategies used depends entirely on the individual learner. It might be useful to carry out the MALQ in class, see what isn’t being used and teaching successful use of particular strategies.

References

Oxford, R (2011) Teaching and Researching Language Learning Strategies. London: Routledge.

Vandergrift, L, Goh, CCM, Mareschal, CJ, & Tafaghodtari, MH (2006) “The Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire: Development and Validation” Language Learning 56:3 September 2006, pages 431-462.

What's changed? Let's do stuff!

Three years of writing this bloody blog and what’s changed, really? I have, but that’s not what I’m talking about. How has the profession changed? It hasn’t. Not a bloody single thing as far as I can tell. Glacial. Maybe a few people have cottoned on to the learning styles myth. That’s it.

So, am I going to just continue glowering at the internet or do something about it? Well, there has to be a balance between working for nothing for a worthy project or cause and getting compensated fairly. So what can I (we?) do?

We can complain about how shit things are (like in Jeremy Slagowski’s great post about a listening syllabus here) and/or put forward an alternative.

We can moan about stuff that doesn’t work and/or see about fixing it. Now, my name is not Answer Man. It’s not even my alter ego. Sometimes, when you find something doesn’t do what you think it’s supposed to do, you ask an expert. Sometimes it’s somebody who works in a shop. Sometimes it’s a book. Sometimes it’s your friends. By talking about stuff, we surely get closer to an answer, at least one more step forward on the path to enlightenment.

Doing stuff, though. This is what I think I need to do. It doesn’t always come off right, but it’s going to be, usually, only as bad as inaction, especially if you think hard about potential risks before acting.

Against the Coursebook Flow for Better Listening

This post is informed by my own research (Jones, 2017), but isn’t exactly part of it. It was partly inspired by a eureka moment at the sink while washing the dishes. I was thinking about coursebooks, and particularly the flow, when the connection came to me. Anyway, more below.

Take a moment to think about how a coursebook lesson flows. No prizes for guessing that it follows PPP. Usually it’s this: Schema activation (recalling and retrieving knowledge about a topic) activity from an image, perhaps some ‘Starter’ questions. Present language, using reading and/or listening text (usually alternating across a unit, with a reading sub-unit and a listening sub-unit). Move on to a grammar exercise or two. Finish with a ‘free’ speaking activity.

I’m going to look at this listening flow. I’m not going to say that schema activation is a waste of time at all but, does it need to be done every time listening is taught? I am going to say no because we don’t always know or have the ability to make reliable predictions about the upcoming content of conversations we are likely to be involved in or overhear. There is also the fact that in a survey I conducted with teachers about what they state their practices and beliefs to be (Jones, 2017), activating schemata massively negatively correlated with teaching bottom-up listening skills. Basically, teachers who say they activate schemata, say they don’t teach bottom-up skills and teachers who say they teach bottom-up skills say they don’t activate schemata. That bottom-up skills are neglected is not a given, however, but it is only the explicitly stated practice of a large minority. So less than half of the teachers I picked up through social media, the freaks who talk about teaching in their free time, teach bottom-up skills explicitly.

Why? “It’s not in the book” actually isn’t the answer. It is usually in the book, but it’s mislabelled as ‘pronunciation’. It’s a chance to practice what John Field (2008) calls ‘microlistening’ (Field, 2008, (ch. 5, p. 19/33), or decoding and practicing listening to features of connected speech in relative isolation to the rest of a larger text. It’s not always fantastic, but I bet, based on a study I did with Japan-based English teachers (Jones, 2016) on beliefs about pronunciation teaching, that it’s omitted by about 20% of teachers, and only taught at word level, with anything longer than phrase level being omitted by roughly half of teachers.

Why? I don’t have evidence for what follows, it’s just a theory, but I think the schema activation picture is a bit more attractive due to the nice flashy image, potentially with a vocabulary bank, compared to a half page made up of IPA characters to target aspects of speech such as weak forms or even scaffolding the decoding of unfamiliar lexical words. Unattractive books (or books that might look difficult due to a lack of images or actually using IPA) won’t be published for fear that they won’t sell, so learners and teachers who may want to use a book are left with the status quo. And the bottom-up listening masquerading as ‘pronunciation’ doesn’t get covered because it isn’t attractive, isn’t as easy to teach as a grammar exercise, and as Ableeva and Stranks (2013) state:

[T]he real purpose of many listening materials, then, appears quite clearly to be one or more of the following: topic extensions; exemplification of grammar; exemplification of functional or lexical items of language; lead-in to a learner speaking activity. All of these

are worthy and defensible aims, but they are not aims which are tied intrinsically to

improving learners’ ability to process spoken language.

(Ableeva & Stranks, 2013. p. 206).

So, it would be nice to have some teachers’ books to tell teachers to make more of the ‘pronunciation’ sections. It would be nice to have the ‘pronunciation’ sections labelled as ‘phonology’ or ‘listening’. It might just then join the dots for a lot of teachers, particularly novice teachers, to build learners skills to help them tackle longer listening texts with more confidence.

References

Ableeva, R. & Stranks, J. “Listening in another language – research and materials” in Tomlinson, B. (ed.) (2013) Applied Linguistics and Materials Development. London: Bloomsbury.

Field, J. (2008) Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: CUP.

Jones (2016) Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices Regarding Listening and Pronunciation in EFL, Explorations in Teacher Development, 23, 1. 11-17 JALT TD SIG.

Jones (2017) English Language Teachers’ Beliefs and Stated Practices Regarding Second

Language Listening Pedagogy and Alignment with Research. Unpublished MA Dissertation. University of Portsmouth.

Shoe on the other foot

I’m no longer absolutely strapped for time so I’m back in ‘I am actively learning Japanese’ mode. There’s a standardised test in December that would be kind of useful to have for jobhunting and stuff. It would also be nice to know I’m being sort of clear.

I’m also taking all of my own advice. I am using monolingual dictionaries (because it’s appropriate to my level), using corpora, reading books again, and listening to radio programmes. I am also taking notes and looking at them.

No lessons. At least not yet. I don’t want to be *that* picky student but I wonder if I would be. I might call up my old Japanese teacher for a crash course before the school term starts again. I just hope that I don’t end up being annoying.

On (being off) Twitter

In the past I have described Twitter as ‘my living room’. It was a place (and we can go on about paradigms of representing networked digital media as actual media or as de facto pseudogeographical sites but I would like to keep the word count down and avoid a reference list, so feel free to think of the internet however you want) I enjoyed being in. Unfortunately, I didn’t own it and therefore I had little way of guaranteeing an environment that would always be pleasant.

In the past I have described Twitter as ‘my living room’. It was a place (and we can go on about paradigms of representing networked digital media as actual media or as de facto pseudogeographical sites but I would like to keep the word count down and avoid a reference list, so feel free to think of the internet however you want) I enjoyed being in. Unfortunately, I didn’t own it and therefore I had little way of guaranteeing an environment that would always be pleasant.

In an essay for my MA, I wrote about why Twitter was not a particularly useful website for learners of English (or other languages) and that it would be unwise for teachers to recommend people with vulnerable senses of self – in part due to to the way L2 learning affects one’s identity – to use Twitter. I said that Twitter was good for language teachers’ CPD.

I now disagree with myself. I now think that Twitter is becoming an ever more toxic venue, with ranting being an ever increasing form of discourse. This makes sense for people selling advertising. The more ranting, the more tweets in argument, the more promoted tweets you can insert into the time lines and the more money you can get.

However, what is the effect on our mental health, individually and collectively? When our phones vibrate in our pockets to give us a dopamine hit, does it really help us to build community or does it build dependency upon likes, retweets, confirmation and identity politics dumbed down to hectoring people who operate under different beliefs? I don’t have answers, but anecdotally, I’d say I disliked the person I became when participating in the Twitter ELT community.

So I left with a rant (see a pattern?) of asking people to not be awful to one another and actually try to be nicer. Perhaps this was wrong. The people who are always nice came out to be nice and imploring me to stay (some while carrying on skirmishes created on/made bigger by Twitter). One user asked if it was something he’d tweeted. I was furious and righteous BUT! I knew I had seen something from a perspective that I’d never appreciated before. I could have said, “Yes, it was,” and been correct; but I would have been equally correct had I said, “No, it wasn’t” because while a particular hectoring series of tweets back and forth made me decide that, yes, finally it was time to delete my account on a website that totally sees Nazism as an acceptable point of view but won’t happily tolerate ordinary users tweeting the words ‘fuck’ or ‘shit’ to its verified users, it was simply one incident building up to a sum of many. I then saw more hectoring, gathered email addresses from my direct messages and deleted my account. I never replied, perhaps rudely. But would it have been ruder to call that person an obscene name in the heat of the moment? I think I feel OK being a bit rude instead of being a shitbag, actually.

What makes it worse is that much of the ranting was and is probably still being done by people I respect immensely. Unfortunately, I am too knackered to be able to read much more of it.

So, Twitter, it’s not me, it’s you. It’s your cynical manipulation of people by boosting controversy (hot topics, or things to get irate about) and having absolutely shit community guidelines.

You can find me on Mastodon until that succumbs to the darker side of human nature.

What does it all have to do with me? A response

Image: Critical Mass bike ride, San Francisco 2007. Public Domain.

Earlier today I read Hana’s post, What does it all have to do with me? You should read it.

She talked about finding debates on how our work, organisations, associations and hierarchies more and more relevant to her and finding it more important to be critical in our profession.

Me, I think I have always been a romantic trapped inside a cynic. You see, I think I am drawn to seeking constant improvement and when others see things as good enough, it sets me off.

There are a million things that I have questions about. Why do so few in Japan’s English conversation schools (eikaiwa) have any knowledge of SLA? Why would you use materials that are designed for a global market if your setting is one with a shared L1? Is pronunciation overlooked because it is difficult to teach well? Is that also the same for listening? Why are Japanese teachers assigned grammar classes and foreign teachers communication classes if the Japanese teachers consult native teachers about grammar so much and native teachers are known for supposedly talking too much? Why do we have a race to the bottom with wages?

It’s talking about these things that gets others going to talk to other people, who in turn talk to others. This can turn into a critical mass. If enough people vote with their feet, change case number come. If we choose to just think things are terrible and say or do nothing, then nothing will happen.

#ELTwhiteboard is not just for writing

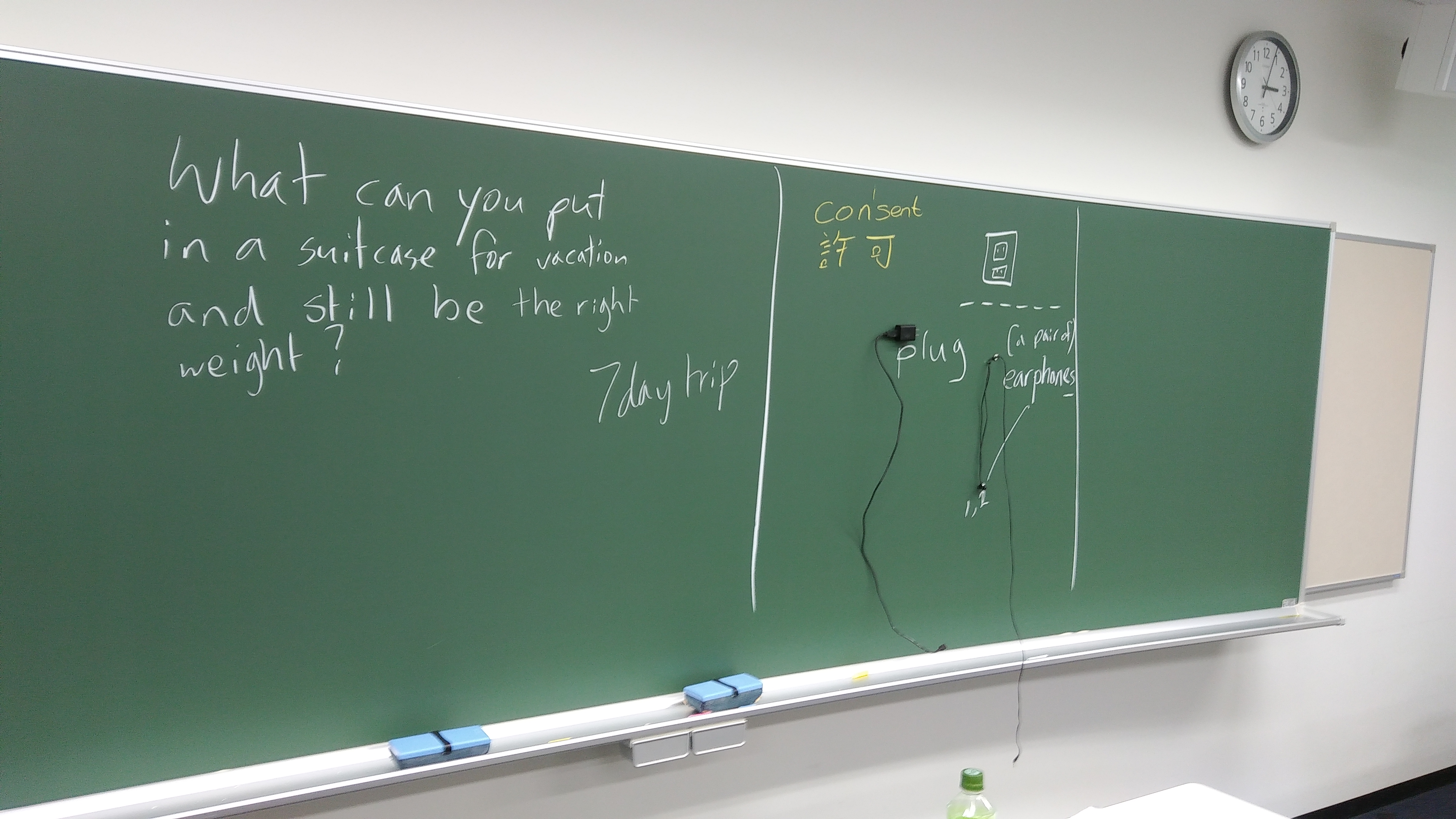

Well, today is something a bit different. I thought I’d show you a picture of my whiteboard near the start of class.

The students were answering the question on the main part of the board. We came upon one of the trickiest sets of loanword-versus-usage problems. Also there were a couple of issues with “(a pair of) THINGs” that is really a pluralised single item.

Luckily I had some really with me. I would have loved to pull the socket of the wall, too.

I almost always have Print Tack (or くつきむし [kutsukimushi] in Japanese) with me. It’s what I use for reading/picture gallery tasks, too.

Do you use the whiteboard or blackboard for anything a bit different?

Hyperreality: The failure in the park didn't happen

The title of this post harks back to my BA Film & Media Studies days at Sunderland, when we were assigned a reading by Jean Baudrillard about how the media portrays (or just doesn’t report) events has ramifications upon the perception of them.

What the hell are you talking about, Marc?

Bear with me, because hopefully it will be worth it. I organised the ELT freefor(u)m Tokyo on Saturday thinking I might bring about a little bit of knowledge sharing and a little bit of solidarity to language teaching. Of course it was a bit daft to think that some people would turn up to the park on either a day they are working or a day when they are off work with families or friends. It seemed to have a lot of support on Twitter. Elsewhere. Not in Tokyo.

Now, if I had dressed this up as a rampant success, would this have made the next one (and there probably will be another one after I have a really long hard look at myself in the mirror and listen to Denzel Washington’s “it takes a wolf” speech from Training Day or something) be even more successful and less of an outlandish prospect? I don’t know. I do know that Anna’s Reflective Practice group gets more than zero people going to it, but that’s after work. My after work is usually ludicrously late, and my not at work is the start or middle of other English teachers’ days.

Anyway, what I did do was be honest: it was not even a one-man-and-his-dog audience (actually, audience is a misnomer because this was supposed to be a crowd thing, in person, and grassroots and other hippie-centric words). It was the flipside of every cool, loner fantasy. Sitting in a park, with a sign, hoping that people would come. I gave it an hour and then buggered off to get coffee and read without needing to wear a jacket. It was less successful than a freeform jazz odyssey. I licked my wounds and sulked.

So, the point, Marc?

The point is that if you have harebrained ideas that involve people you need to get actual commitment from them, and you know, you could dress it up and not have a failed project in your results when people Google you, or you could try and learn from it even though you get massive bruises on your ego and feel like an arse for wasting your time and energy.

I got loads of feedback from my lovely Twitter network, including some awesome, detailed feedback from TaWSIGgers – and maybe this idea has legs, maybe elsewhere, maybe another day or time. If it doesn’t, well, even though the first Gulf War never happened, everyone is quite aware that the second one did, aren’t they?

So, what’s next?

Keep on with this, I think. I’ve been told not to give up, so I figure, if there’s still absolutely nobody by the third try, it’s not going to be me doing it. I need help; help might even be on the way. So although I deleted the ELT freefor(u)m blog in a tantrum, it’s not quite as moribund as it might seem.

Positive Steps (Vanguards Wanted)

I’ve been, and still am, disillusioned with the industrial side (as opposed to the professional side) of English Language Teaching. This includes lack of professional development, overbearing influence of coursebooks and the massive global ELT publishers, deskilling by publishers and large chain schools and precarious working conditions. I’ve always tried to avoid being a naysayer in that when I’ve said ‘nay’, I hope that there’s at least one alternative proposed. Being that I believe action is necessary, I am going to propose action that sympathetic parties may wish to follow up on.

Work in loose, broad-church, accessible Special Interest Groups (SIGs)

IATEFL and TESOL International do not have the monopoly on operating SIGs. There is TaWSIG but other than that there are others that are SIGs by nature if not by name. The Dogme in ELT forum was such a thing. TEFL Equity Advocates is another. There is also ELT Advocacy Ireland, the Women in ELT group on Facebook, The C Group, and I suppose what we at #TBLTChat have been trying to do and what TLEAP are doing.

Realise it’s a broad church and many people do a range of things with varied experiences and dialogue can help us grow through shared practices, ideas, stories and knowledge. This then creates a culture. What do you care about? What are the itches you’re not getting scratched? Are there people who’ll do this with you? You don’t have to have a lot of people to start with; summoning shared energy shouldn’t be a problem.

Don’t Like Something? Make Something Else!

Don’t like textbooks? Try materials light teaching or making your own materials. Tell others.

Are listening materials rubbish? Could you make your own website? Tell others.

Do you hate this blog or feel it neglects things things? Make your own. Tell others.

We can, and I am reluctant to dictate but we should try to make the world how we would like it to be rather than settling for how it is. This change will not come easily but nor will it fall in our laps automatically without any kind of effort being applied.

We are all polymaths. We all have other skills and interests that can be brought together to build a better environment.

Commit but See Other People

You have your ideas and interests and you are what you are because of them. With other people’s knowledge and skills you can build further and better than you might otherwise do alone. Your loose, broad-church SIG can only benefit from outside knowledge and expertise.

Some of this, at least initially, may involve working for free

However, the beneficiary of this free work is you and your community, so you aren’t slaving away for someone else. You may even be able to make money from it later because people don’t mind paying for things with value, they just mind being ripped off. You then have a model, with this work, of how things could be. This might take reiteration. Keep looking, even if there are faults. Someone, somewhere might benefit.

Hopefully this is good for thought for some of us about our place in the world and gives us a more positive idea of where we might go next.

I’d love comments here, especially if you use the comments to build your own SIGs.