It’s that old Corporate ELT is killing me slowly trope. Hang on to your hats, comrades, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

So, the coursebooks palaver came up again on Geoff Jordan’s blog. I have written on this before. The main change in my ideas is that instead of Dogme or Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) being the utopia we should all aim for, what is needed to get teachers to go with something better than a textbook is an alternative.

In the aforementioned post, Steve Brown said that what is needed is not any other kind of alternative but for teachers to take agency: choose what the materials are, or choose to choose with the learners, or whatnot. He is right, but I think there needs to be a bit of handholding to get there.

I’ve seen comments saying that it takes bloody ages to plan a TBLT lesson, and it does when you first start. Similarly CELTA-type lessons take bloody ages when you first start. No qualifications? Think to your first week on the job. Lesson plans took forever. Anything takes ages when you first start.You need to think about whether the initial time investment will pay off or not. You are reading a blog about teacher development, so ostensibly you are open to this seeing as you are reading this instead of playing video games or trolling Trump supporters.

So, let the handholding begin. Or the push to start.

What can I use instead of a coursebook?

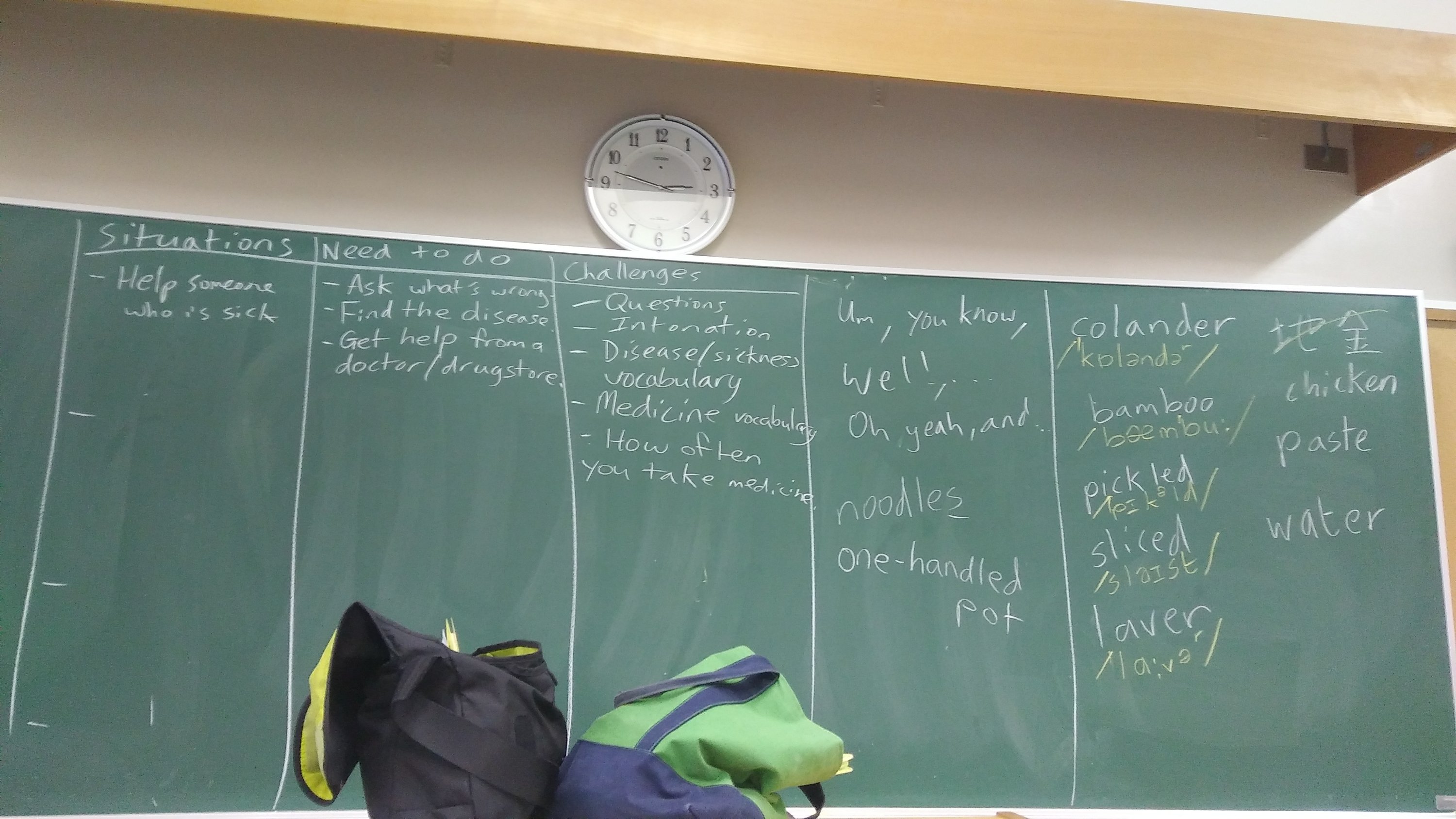

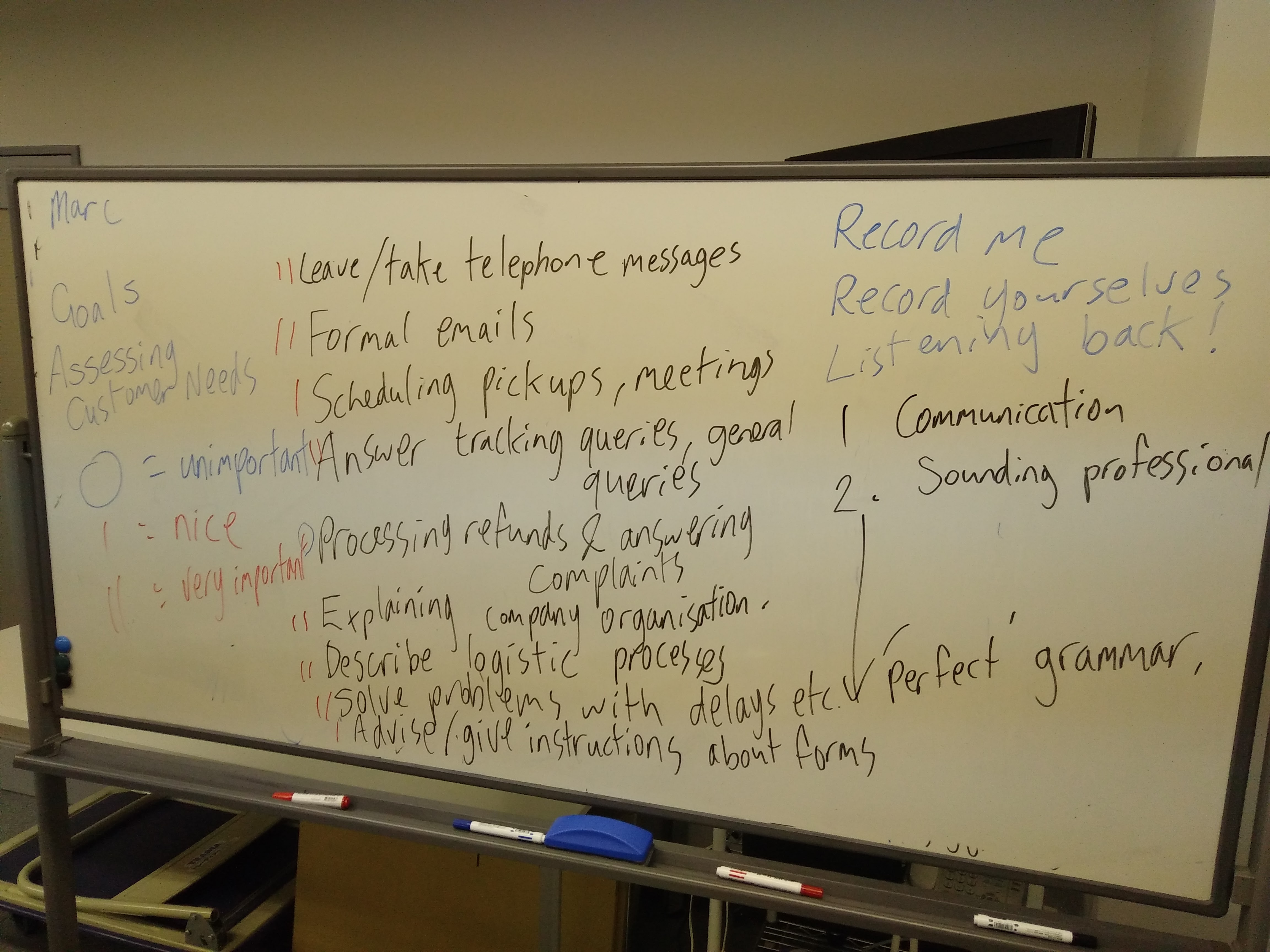

Have a think (always a good idea) about what your learners need. Asking them is often a good idea, though teenagers might tell you they need about 3 hours in bed and that they need to do gap-fills of A1 vocab. They don’t. Assess. What can they do? What can’t they do? What aren’t you sure they can do? The answers to this should rarely be “They can’t do the past tense with regular verbs” or something. Maybe “They can’t answer questions about the weekend” is better. Cool. That is something we can chuck into the syllabus, if we think that our learners need this. If they don’t, don’t put it in. But why did you bother assessing it otherwise?

With all this information, you can create a syllabus/course. Sequencing it is a bit of a bugger because you want to think about complexity, what is likely needed toward the start and middle to get to the end, recycling language and such. However, you and your learners have control. This is not the kind of thing to put on a granite tablet. If it seems to need a bit of something else, do that.

But what do I do?

Teach the skills you need to teach. Potentially this is all four skills of reading, listening, writing and speaking. There are books about ways to teach these. You might want to browse Wayzgoose press. Also The Round minis range has some very interesting stuff, as does 52. If you get a copy of Teaching Unplugged, I find it useful.

You and your learners can then source texts from the internet (which a lot of textbooks do anyway so you are cutting out the middleman), edit for length (nice authentic language) or elaborate and spend longer with (that is, put in a gloss at the side or add clauses explaining the language). You can create your own, too, which sounds time consuming but might not be the pain in the arse you think it is. You can also put in some stuff that is rarely covered in textbooks like pronunciation and how to build listening skills, microlistening, and more (a bugbear of mine).

There are also lots of lesson plans on blogs (including here). If you have some good lessons that have worked for you, they might work for others, who can then adapt them. With a book, there are sunk costs and learners will want to plough through the lot if they have bought it. If you have a lesson plan to manipulate, without having sunken money into it bar some printer paper, you and your learners get more control and hopefully smething more suited to them than something chosen by an anonymous somebody in London or New York.

If I’m going to use texts, I might as well use a textbook!

You could, but think of all the pages of nonsense you have to skip. Think of the time spent with learners focussing on pointless vocabulary like ‘sextant’ (thanks Total English pre-intermediate). You have an idea. You know your learners, or at least the context. There is also a ton of stuff on the internet. May I point you to the Google Drive folder at the top of this blog. All the stuff in there is Creative Commons Licensed so you can change it if it isn’t perfect, copy it for your learners, and because I already made it and was going to anyway, it’s free. There is also Paul Walsh’s brill Decentralised Teaching and Learning. There are also ideas to use from Flashmob ELT.

So

You have these ideas to use, modify, whatever and put into timeslots. You can move them around. You have the means, now, if you decide it’s worth a go, stick with it for a few weeks at least, so you can get into the swing of it. If you like it, leave a comment. If you hate it and I’ve ruined your life (and be warned that not all supervisors, managers and even learners are open to this at first. Check, or at least be aware of this. If your learners say they want a book they might just mean they want materials provided and a plan from week to week) leave a comment.

If you think I’m talking nonsense, I’d seriously love you to leave a comment. Tell me why.

If you want help with this, I’m thinking of using Slack for a free (yes, really, at least initially) course type thing, say an experimental three weeks, where I help you sort out how to go about things (together; top-down isn’t how I do things), help with any teething troubles and so on. If you’re interested, contact me.

Well, Sunday night, eleven o’clock and 1000 words. I’m going to bed. Let’s sleep on it.